All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Revisiting the Risk Factors for Multiple Symptoms of Temporomandibular Disorders: A structured Cross-sectional Study

Abstract

Background:

The risk factors for Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD) are extensively studied, but the results showed no consistency. Only a small proportion of patients with TMD are likely to seek help and require treatment. Those individuals tend to present with multiple symptoms. This cohort of patients was not well investigated.

Objective:

The study aimed to examine the association between possible risk factors for presentation with multiple TMD symptoms.

Methods:

A population-based, cross-sectional study was conducted across 2101 individuals with an age range of 19-60 years. The condition was assessed via a detailed questionnaire comprising symptoms, habits, dental history, general health, sleep patterns, along with the completion of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale, followed by an examination of the hypothesized clinical signs. The obtained data were tabulated and characterized the study population in a descriptive analysis in forms of percentages and frequencies. The significance level was set at P-value less than or equal to 0.005. The chi-squared test was implemented to assess the relationship between the multiple TMD symptoms reported and the potential risk factors.

Results:

Most participants reported a variable amount of stress. Moreover, 1528 (72.7 percent) mentioned abnormalities in sleep. About 80 percent had at least one TMD-related symptom. The multiple symptoms of TMD were identified among the 741 individuals. The following risk factors demonstrated association with a robust statistical significance (P=0.00), 1) occupation, 2) sleeping problems, 3) health concerns, 4) traumatic dental treatment, 5) various somatic symptoms, and 6) elevated HAD scale. When the outcomes of the clinical examination were analyzed, the statistical assessment could link soft tissue changes, namely; the cheek ridging and tongue indentations (P 0.00), with multiple symptoms of the condition.

Conclusion:

Multiple TMD symptoms were prevalent among individuals with elevated stress, abnormal sleep pattern, traumatic dental treatment, elevated HAD scale. The results highlighted the importance of psychological factors in the pathogenesis of TMD.

1. INTRODUCTION

The Tempro Mandibular Disorders (TMDs) are identified as a major cause of the non-dental pain in the orofacial region [1]. TMDs are not considered as a single syndrome with one common or multifactorial etiology anymore but are a collection of heterogeneous correspondent disorders with underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms. Therefore, enriched clinician knowledge and awareness of TMDs along with the differential diagnosis is of fundamental and upmost importance [2]. The condition affected the jaw musculature, the temporomandibular joints, and associated structures or both and was given several synonyms, which reflect the lack of common understanding of the disease. However, in many patients, the symptoms are not confined to the temporomandibular region but extend to the neck, shoulders and even the upper, middle, and lower back, the upper arms, and the knees [3]. The affected individuals usually present with pain and symptoms of masticatory system dysfunction are a prevalent disorder most commonly observed in individuals between the ages of 20 and 40. Approximately one fifth to one-third of the population has at least one TMD symptom, but 3.6% to 7% of this population may seek medical assistance [4-7].

| Elements for Clinical Examination |

| 1. Mandibular retrognathia |

| 2. Limitation in mouth opening |

| 3. The presence of deep Incisor bite |

| 4. Anterior or posterior tooth wear |

| 5. Tenderness on the temple area, TMJ and back/sides of the neck |

| 6. Marginal tongue indentation |

| 7. The presence of various dental prosthesis |

| 8. The presence of a cheek ridging |

| 9. Presence of the jaw Bony exostosis |

| 10. Loss of first molar tooth/teeth |

For decades, the risk factors and underlying etiology for TMDs are subject to debate. The etiology is widely regarded as multidimensional, biomechanical in forms of deranged occlusion and displaced meniscus, neuromuscular, psychosocial, and neurobiological factors explained by central somatization [8]. Although the medical library is rich in papers on TMDs, there's a consistent pattern of disagreement on what may cause, initiate, and worsen the morbidity of patients with TMDs. This has resulted in a lack of standardized treatment protocols for treating the condition. This research is aimed at improving understanding of the disease through the analysis of the association between potential risk factors and the presentation of multiple TMD symptoms.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was a cross-sectional and random population-based that included a pre-validated, self-administered questionnaire, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD Scale), and clinical examination of the signs likely associated with the TMD. The Research Ethics Committee (REC) of the University of Ajman reviewed and approved the study protocol with reference SS2016/17-06 and was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The questionnaire focused on the demographic data of the participants, in addition to the exploration of the wide range of TMDs symptoms with questions adapted from the anamnesis suggested by the American Academy of Orofacial Pain [9]. The next part investigated the potential risk factors reported in the literature like abnormal oral behaviors, history of traumatic dental visits, orthodontic treatment, general health issues and worries, and sleeping disorders (Table 1). The sleeping problem questions were modified from the scale published by Jenkins and coworkers [10]. The participants were then asked to complete the HAD scale questionnaire form. The degree of anxiety and depression was calculated according to total scores as follows: A) 0-7: normal or absence of anxiety and depression; B) 8-10: cause of concern (borderline); and C) 11-21 and above; a probable clinical case requiring assessment and possible psychiatric interventions. The third component of this work involved a clinical examination for the features linked to patients with TMDs in the available literature and are listed in Table 2.

The data obtained was computerized using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 64-bit to perform the statistical analysis. To characterize the study population, a descriptive analysis in the form of percentages and frequencies was performed. The P-value was set to below or equal to 0.005. Chi-squared analysis was used for the evaluation of the association between the multiple TMD symptoms and their possible risk factors. These factors were also assessed for their potential contribution to the multiple TMD symptoms via calculation of the Odds ratios (OR). The ratio was measured at 95% confidence interval calculated according to Altman, 1991 [11].

3. RESULTS

3.1. General Characteristics of Participants

Each participant (2101) completed the TMD symptoms and risk factors questionnaire. They also completed the standard HAD scale form. However, only 1456 (69.3%) agreed to undergo the clinical examination component of the study. The population of the study was predominantly females (1741, 82.9%), within the age range of 19 to 60 years. The study targeted people under the age of 50 (2036) with the most abundant age group of the 3rd decade, which made 60.6% (1274) of the study sample. Most of these young participants were university students (896). Only 10.3% of the participants reported a smoking habit. The majority of participants (94.5%) reported a variable amount of life stress. The differential self-report of the stress revealed the following; occasional incidents (1013, 48.2%), frequent episodes (627, 29.8%), and constant stressful life reported by 259 (12.3%) participants while the rest of participants (202, 9.6%) did not recall any significant stresses. When asked to describe their personalities, more than one-third (817) of the participants described themselves as sensitive. On the contrary, another one third were calm individuals, but one-fifth of the respondents (423) believed that they get angry or upset very quickly or have a neurotic personality. Around two-thirds of the participants reported variable degrees of sleeping difficulties (1528). Around one-quarter of participants (552) reported concern about their general health status. The investigation of the history of rough or potentially traumatic past dental treatments revealed that the long dental visits were the most commonly reported incidents reported in 383 cases (18.2%). On the other hand, more than one third (794) of participants reported multiple potentially traumatic dental treatments, including orthodontic treatment and surgical extraction of teeth.

| Symptoms | HAD Scale | Total | Sleeping Problems | Total | Tenderness of muscles and joint | Total | |||||||

| Normal | Borderline | Elevated | Occasional | Usual | on Pills | No problem | Present | Absent | |||||

| Earache | Count | 42 | 24 | 99 | 165 | 71 | 27 | 1 | 56 | 156 | 35 | 83 | 118 |

| % of patients the symptom | 25.5% | 14.5% | 60.0% | 100% | 43% | 22.5% | 0.6% | 33.9% | 7.9% | 29.7% | 70.3% | 100% | |

| Morning headache | Count | 22 | 80 | 276 | 378 | 195 | 83 | 5 | 95 | 378 | 132 | 146 | 278 |

| % of patients the symptom | 5.8% | 21.2% | 73.0% | 100% | 51.6 % | 21.9% | 1.3 % | 25.1% | 18% | 48.5% | 52.5% | 100% | |

| Jaw/neck fatigue | Count | 31 | 26 | 61 | 118 | 71 | 25 | 1 | 21 | 118 | 59 | 29 | 88 |

| % of patients the symptom | 26.3% | 22.0% | 51.7% | 100% | 60.2% | 21.1% | 0.8% | 17.8% | 5.6% | 77% | 33% | 100% | |

|

Difficulty in opening the mouth |

Count | 7 | 12 | 38 | 57 | 29 | 5 | 1 | 22 | 57 | 31 | 15 | 46 |

| % of patients the symptom | 12.3% | 21.1% | 66.7% | 100% | 50.9% | 8.8% | 1,8% | 38.6% | 2.7% | 67.4% | 32.6% | 100% | |

| Jaw tires easily when chewing | Count | 6 | 5 | 49 | 60 | 38 | 5 | 0 | 17 | 60 | 26 | 15 | 41 |

| % of patients the symptom | 10.0% | 8.3% | 81.7% | 100% | 63.3% | 8.3% | 0% | 26.3% | 2.9% | 63.4% | 36.5% | 100% | |

| Teeth sore when biting | Count | 15 | 16 | 55 | 86 | 47 | 21 | 0 | 18 | 86 | 22 | 32 | 54 |

| % of patients the symptom | 17.4% | 18.6% | 64.0% | 100% | 54.7% | 24.4% | 0% | 3.2% | 4.1% | 40.7% | 59.3% | 100% | |

| Jaw clicks before opening wide | Count | 16 | 13 | 63 | 92 | 43 | 22 | 0 | 27 | 92 | 28 | 17 | 45 |

| % of patients the symptom | 17.4% | 14.1% | 68.5% | 100% | 46.7% | 23.9% | 0% | 29.3% | 4.4% | 62.2% | 37.8% | 100% | |

| Multiple | Count | 85 | 96 | 560 | 741 | 396 | 172 | 7 | 166 | 741 | 307 | 254 | 561 |

| % of patients the symptom | 11.5% | 13.0% | 75.6% | 100% | 53.4% | 23.3% | 0.9% | 22.4% | 35.3% | 54.7% | 45.3% | 100% | |

| No Symptoms | Count | 81 | 47 | 276 | 404 | 197 | 71 | 4 | 132 | 404 | 58 | 167 | 225 |

| % of patients the symptom | 20.0% | 11.6% | 68.3% | 100% | 48.8% | 17.5% | 21.1 | 32.7% | 19.2% | 25.8% | 74.2% | 100% | |

| Total | Count | 305 | 319 | 1477 | 2101 | 1087 | 441 | 19 | 554 | 2101 | 698 | 758 | 1456 |

3.2. Temporomandibular Disorder Symptoms and their Potential Risk Factors

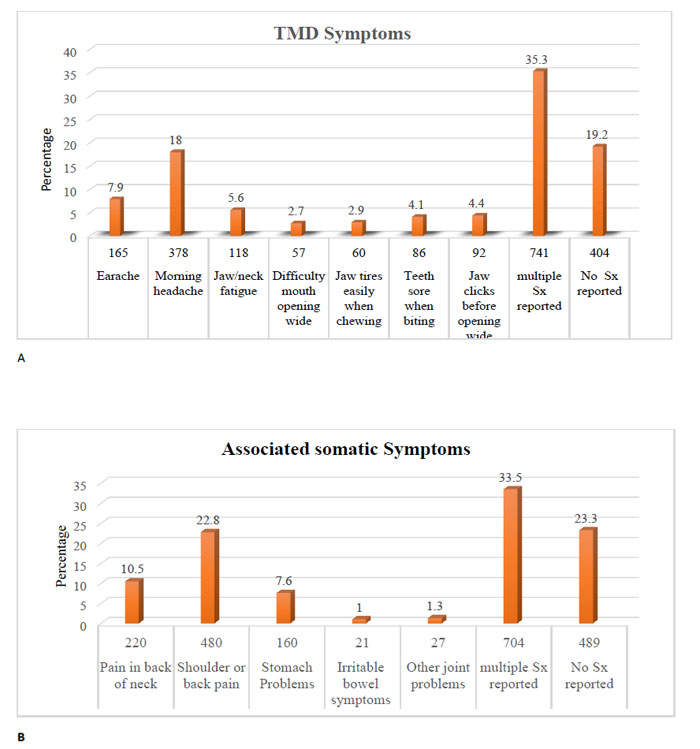

Around 80% of participants (1697) had experienced at least one symptom related to the TMDs. The most commonly reported single symptom was morning headache, which was reported by 18% (278), followed by a temple headache in 118 cases. On the other hand, the least reported symptoms reported were the joint clicking and pain while chewing regular meals. The control group included 404 individuals without a history of any symptoms related to the TMD (Fig. 1a).

More than one-third (741) of the study population reported more than two symptoms (referred to as multiple) of the TMDs. The symptoms were not limited to jaw muscles and joints in two-thirds of cases (1612). Around one-third of respondents (704) complained of multiple remote somatic symptoms, including neck, shoulders, and other joints and back pain, in addition to various stress-related gastrointestinal disturbances (Fig. 1b). The descriptive analysis and cross-tabulation showed a variable association of study risk factors against symptoms. A representative sample of the data is shown in Table 2.

Using the Chi-square test, the following self-reported risk factors were associated to the patient presented with multiple TMDs with high statistical significance (P .000-.002); 1) occupation, 2) sleeping problems, 3) an increased concern about health status, 4) history of potentially traumatic dental treatment, 5) co-existence of multiple somatic associated symptoms, and 6) elevated HAD scale (Table 3). The results also highlighted the probable role of the abnormal oral behaviors like bruxism in the precipitation of the multiple TMD symptoms despite the lack of statistical significance (P 0.107). The cross-tabulation analysis revealed that the most commonly reported pattern of bruxism was that taking place while sleeping and this habit was associated mainly with multiple TMD symptoms (38.5%), with morning discomfort and headache being the most prevalent presentations (19%).

The clinical screening for hard and soft tissue changes could only relate the tongue indentations and cheek ridging to the presence of multiple TMD symptoms (Table 4). The risk assessment was also confirmed by the outcome of the odds ratio calculation. The later statistical assessment showed the association of the same risk factors obtained from the questionnaire, the HAD scale, and the clinical examination, that are shown in Table 5.

| - | Multiple TMD Symptoms | Occupation | Reported Amount of Stress | Personality Trait Self-Description | Sleeping Disorders | Health Concerns | History of Rough Dental treatment | Associated somatic symptoms | Reported Bruxism | HAD Scale | |

| Multiple TMD Symptoms | P value | .010 | .061 | .381 | .002 | .000* | .000* | .000* | .107 | .000* | |

| Occupation | P value | .000* | .001* | .001* | .001 | .592 | .568 | .112 | .031 | .001* | |

| Reported Amount of Stress | P value | .061 | .001* | .000* | .000* | .005 | .914 | .546 | .556 | .000* | |

| Personality Trait Self-Description | P value | .381 | .001* | .000* | .000* | .135 | .215 | .027 | .013 | .110 | |

| Sleeping Disorders | P value | .002 | .001* | .000* | .000* | .254 | .409 | .438 | .924 | .000* | |

| Health Concerns | P value | .000* | .592 | .005 | .135 | .254 | .715 | .004 | .037 | .000* | |

| History of Rough Dental treatment | P value | .000* | .568 | .914 | .215 | .409 | .715 | .000* | .000* | .505 | |

| Associated Symptoms | P value | .000* | .112 | .546 | .027 | .438 | .004 | .000* | .000* | .060 | |

| Reported Bruxism | P value | .107 | .031 | .556 | .013 | .924 | .037 | .000* | .000* | .977 | |

| HAD Scale | P value | .000* | .001* | .000* | .110 | .000* | .000* | .505 | .060 | .977 | |

| - | Multiple TMD Symptoms | Mandibular Retrognathia | Deep Bite | Tooth Wear | Tongue Indentation | Dental Prosthesi | Cheek Ridging | Bony Exostosis | Loss of Molar teeth | |

| Multiple TMD Symptoms | P value | .688 | .350 | .586 | .000* | .160 | .000* | .155 | .879 | |

| Mandibular Retrognathia | P value | .688 | .000* | .297 | .573 | .007 | .000* | .007 | .792 | |

| Deep Bite | P value | .350 | .000* | .000* | .009 | .015 | .000* | .156 | .486 | |

| Tooth Wear | P value |

.586 | .297 | .000* | .590 | .013 | .629 | .454 | .521 | |

| Tongue Indentation | P value | .000* | .573 | .009 | .590 | .001* | .000* | .390 | .026 | |

| Dental Prosthesis | P value | .160 | .007 | .015 | .013 | .001 | .331 | .000 | .000* | |

| Cheek Ridging | P value | .000* | .000* | .000* | .629 | .000* | .331 | .667 | .077 | |

| Bony Exostosis | P value | .155 | .007 | .156 | .454 | .390 | .000* | .667 | .000* | |

| Loss of Molar teeth | P value | .879 | .792 | .486 | .521 | .026 | .000* | .077 | .000* | |

| - | Sig. | odds ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||

| Occupation | .295 | .928 | .807 | 1.067 |

| Perception of Stress | .758 | 1.034 | .834 | 1.282 |

| Perception of Personality | .842 | 1.018 | .857 | 1.209 |

| Sleeping problems | .036 | .843 | .720 | .989 |

| Elevated HAD scale | .000* | 1.502 | 1.202 | 1.878 |

| General health Concerns | .000* | 1.234 | 1.117 | 1.362 |

| Self-report of Bruxism | .818 | .991 | .917 | 1.070 |

| Presence of other somatic symptoms | .000* | 1.148 | 1.064 | 1.238 |

| History of multiple rough dental treatment visits | .000* | 1.240 | 1.165 | 1.320 |

| Mandibular Retrognathia | .205 | 1.373 | .841 | 2.241 |

| Anterior deep bite | .356 | 1.244 | .782 | 1.979 |

| Tooth wear | .794 | .960 | .707 | 1.303 |

| Tongue Indentation | .000* | .451 | .309 | .657 |

| Presence of dental prosthesis | .014 | .992 | .863 | 1.139 |

| Cheek Ridging | .000* | .414 | .262 | .652 |

| Jaw bone exostosis | .493 | 1.105 | .830 | 1.472 |

| Loss of first molar teeth | .062 | .687 | .464 | 1.019 |

4. DISCUSSION

TMDs are common disorders and are encountered by a wide range of medical and dental professionals. Because of the diversity of clinical presentation, many cases may not be diagnosed correctly and subsequently subjected to unnecessary investigations and treatments. This study attempted to characterize the patients of TMDs along with their risk factors to help the clinician address such patients more efficiently. This investigation has shown that the TMD symptoms are common in the community, and the major risk factors are related to stress and anxiety with less direct contribution of the pure mechanical factors in the development of the condition. The strength of this study comes from the wide spectrum of aspects of TMD examined together on a relatively large cohort of the population. The inclusion of the TMD symptoms questionnaire, general health worries, self-report of personality trait, sleep disorders, anxiety, and depression scale, along with a clinical examination, was not previously reported in a single study. Furthermore, this study is population-based and, therefore, likely to include an unselected group of mild cases which usually do not report to clinics. The report shows that the TMD symptoms affect a good proportion of the population with around three-quarters of society having at least one symptom that could be linked to the condition. This outcome was in line with many previous reports [12, 13]. However, the prevalence in this study was higher than in other investigations [5, 14-16]. It is doubtful that such inconsistencies are due to disparity in the populations studied. A much more likely justification is to be found in the criteria cited in the studies to define the condition, in addition to the variation in the methodology and sample size in different studies as some were limited to questionnaires, and others included clinical evaluation of participants. The wide disparity of results of TMD population-based previous studies has created confusion regarding the accuracy of prevalence figures, and more importantly, citing individuals who actually require treatment. Based on the demand for treatment, about 3-7% of the population seeks treatment for their TMDs [13, 17, 18]. This proportion of the population likely to require treatment is individual with multiple TMD symptoms. That is why we examined the risk factors among this particular group. Halder et al. [19] concluded that psychological distress, fatigue, health anxiety, and illness behavior are predictors of future onset rather than merely a consequence of somatic symptoms like abdominal pain. The accuracy of using self-reported general health may be questioned. Still, several papers have indicated that it could be a valid measure indicating the magnitude of the individual concern of their well-being, especially as there is a lack of a standard method to classify the overall health in epidemiological researches [20, 21].The results indicate a clear correlation between the general health conditions of the participants in this study and the presence of the TMD symptoms. The individuals who are concerned about their health feel uncertain and anxious and may suffer from sleeping disorders, abnormal oral activities, and other manifestations of central sensitization with an increased risk of developing multiple TMD symptoms. Around one-fourth of the participants of this study have reported the presence of multiple symptoms of TMD, with morning headache being the most reported symptom. On the other hand, the presence of the morning headaches and jaw muscle aches in the TMD patients is likely related to the presence of the nocturnal bruxism since muscles would undergo non-functional activities during the late deep phase of sleep [22]. Moreover, Alvarez et al. [23] also reported a 50% - 90% incidence of headache and tenderness in the temporal region and masseter muscles in individuals with abnormal oral behaviors. However, morning headaches can also be a symptom of the tension-type headache, which is why it should be considered in the differential diagnosis. The TMDs and tension-type headache, in many patients, are characterized by the absence of organic pathologies or degenerative disorders. Both conditions have had debatable etiologies with the psychological factors considered to play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of the three conditions. In connection with this trend, this study shows that more than half of the participants reported an elevated HAD scale, which was closely associated with the presence of multiple TMD symptoms.

CONCLUSION

Hence, these results go together with what is previously reported by various investigators, where psychological factors play an important role in the development and persistence of the TMD symptoms [24, 25]. Furthermore, the improvement of the psychology of the individuals with TMDs has been reported to positively affect the treatment outcome and help the patient to cope better with their long-standing symptoms [26] [27, 28]. Nevertheless, the 701 participants (33.4%) participants who reported an elevated HAD scale also reported the presence of abnormal oral behaviors, especially nocturnal bruxism. This correlated with the previously agreed on in the literature that bruxism can reflect the individual's stresses and trial to escape the fears and the depression or the anxiety that they might be going through. Abnormal oral behaviors have been reported as a means of releasing accumulated tension and stress [29]. However, others have observed no such association between bruxism and TMD [23, 30-34]. Therefore, from the literature, it is deduced that it is bruxism, which is caused by the psychological stresses or depressions that leads to the occurrence of TMD symptoms and not the one present when some mild malocclusions are there [35]. The biopsychosocial theory, first introduced by Schwartz [36], stated that TMDs are a result of the interactions between biological parts (TMJ and muscles), and the psychological and social state. Accordingly this will yield the occurrence of the abnormal oral behaviors. Traumatic dental experience tends to increase anxiety [37]. It was also noted that individuals with a history of rough dental treatment meet most of the criteria for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). The impact of the adverse dental experience was comparable to that of disasters like road traffic accidents and even terrorist attacks [38, 39]. The correlation noted on a cohort between the history of rough dental treatment and two possible mechanisms may explain the presence of the multiple symptoms. The first is the mechanical trauma that may directly injure the stomatognathic structures. The second is the psychogenic impact of the potential PTSD caused by that experience. The literature attempted to correlate several changes in the hard and soft tissue compartments of the stomatognathic system to the TMD. This investigation, however, could only relate the soft tissue changes seen on the tongue and cheeks but failed to associate any of the dental or bony changes with the presence of multiple TMD symptoms. Both cheek ridging and the tongue indentations appear to be directly linked to the active and aggressive night grinding or clenching. These changes reflect the repetitive contraction and the pressure caused by the swallowing that follows the aggressive bruxism activities. It seems that the hard tissue changes are the wear and adaptive changes of slow chronic abnormal oral behaviors that may not be aggressive enough to contribute to multiple TMD symptoms. In conclusion, it is recommended that all treatment of TMD should primarily focus on improving the psychological state and terminating any abnormal oral behaviors. Secondly, the managing practitioner should consider relieving the muscular and articular symptoms resulting from long-term abnormal oral behavior.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) of the University of Ajman, UAE, with reference SS2016/17-06.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals were used in this research. All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Written informed consent was obtained from participants prior to inclusion.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

Not applicable.

FUNDING

No fund or financial support was received for this work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author declares no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.