All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Successful Non-surgical Management of a Mandible Fracture Secondary to Medication-related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw: A Unique Case Report

Abstract

Background:

Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) may be a severe side effect of bone-modifying agents.

Objective:

Pathologic fractures treatment in patients with MRONJ remains challenging. The authors reported a unique case of successful non-surgical management of a mandible fracture secondary to MRONJ.

Methods:

A 78-year-old osteoporotic woman with a 4-year history of oral bisphosphonate therapy and a compromised dental condition developed an MRONJ-related right mandibular body fracture. Treatment consisted of systemic antibiotic administration (amoxiclav and metronidazole) and chlorhexidine mouthwash.

Results:

Follow-up visits revealed progressive healing of the mandibular fracture with bone callus formation and complete recovery of the ipsilateral lip and chin sensitivity after one year.

Conclusion:

Non-surgical management of pathological fractures related to MRONJ might be of interest in patients that refuse any type of surgery, but preventive measures, such as careful dental examination, should be taken before start antiresorptive therapy and during the treatment. The authors reported the first case in the literature of successful management of a mandibular fracture secondary to MRONJ with only antibiotics and mouthwashes.

1. INTRODUCTION

Bone-modifying Agents (BMAs), such as bisphosphonates or denosumab, can prevent bone resorption and reduce the risk of skeletal-related events. BMAs are widely used in patients with osteoporosis or metastatic bone disease [1].

Medication-related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (MRONJ) is a rare infectious complication that can occur in patients with current or previous treatment with BMAs or antiangiogenic drugs [1-4].

MRONJ is defined as exposed bone or bone that can be probed through an intraoral or extraoral fistula in the maxillofacial region that has persisted for more than eight weeks in patients without a history of radiation therapy to the jaws or obvious metastatic disease to the jaws. MRONJ may develop spontaneously or can be induced by invasive dental procedures [1-4].

The MRONJ classifications of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) identified three stages of disease based on the severity of signs and symptoms: the presence of a pathologic fracture is a specific sign of a stage 3 lesion [3].

The pathophysiology of MRONJ has not been clearly elucidated, but the principal evidence-based mechanisms of pathogenesis include altered angiogenesis and bone remodeling, infectious/inflammatory processes, lack of immune resiliency and soft-tissue toxicity [5, 6].

Long-term therapy with BMAs leads to the accumulation of poor bone healing and micro-damage in the skeleton that could result in complications such as atypical bone fractures [7].

In a recent meeting, a group of researchers of the Workshop of European Task Force on MRONJ highlighted that patients who are receiving BMAs and who present with clinical signs other than probing bone fistula or frank bone exposure (chin or lip numbness, mandible fracture, tooth mobility/loss, unexplained pain or swelling in the oral cavity) continue to remain excluded from MRONJ case definition. At the same time, the authors suggested that the time requirement of an 8-week observation of potential MRONJ manifestation to fit the case definition may no longer be necessary [8].

Many authors have investigated the efficacy of non-surgical versus surgical treatment of MRONJ: non-surgical treatment may be a valid management option for infection control and symptoms reduction, but the surgical treatment seems to be superior in promoting long-term mucosal healing and in terms of the absence of symptoms or signs indicative of bone necrosis [8-10].

We report a case of a 78-year-old osteoporotic woman with a mandible fracture secondary to MRONJ successfully treated with antibiotic therapy alone.

2. CASE REPORT

This case report is presented in accordance with the CARE Guidelines (https://www.care-statement.org/).

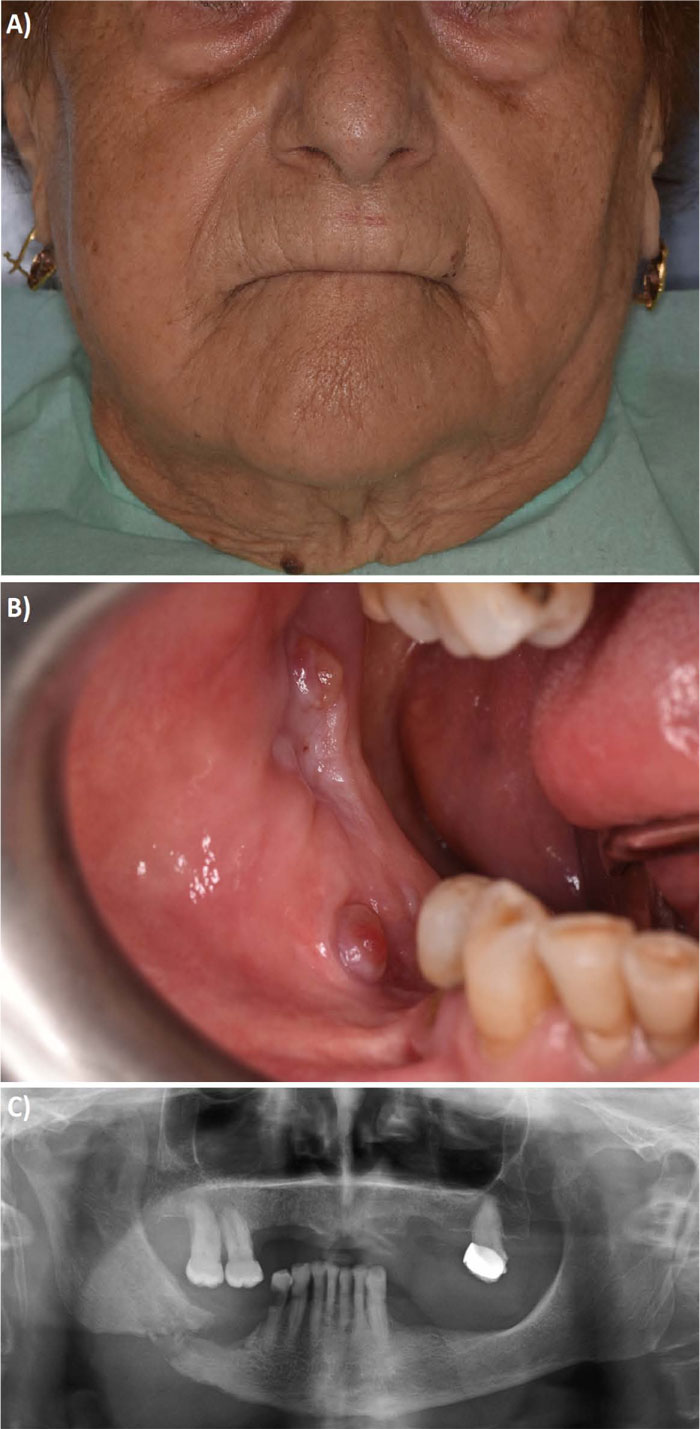

A 78-year-old woman was referred to our hospital in March 2019. Her family dentist's prescription indicated swelling of the right side of the face, without a history of recent trauma. In addition, since February 2019, the patient had localized pain in the right mandibular body. Patient’s medical records revealed a history of osteoporosis and pathological femoral neck fracture surgically treated by a prosthetic joint replacement 2 years earlier. Her comorbidities included hypercholesterolemia and kidney stones, without a history of smoking. She has a 4-year history of systemic bisphosphonate therapy based on intramuscular administrations of clodronic acid (200 mg/4ml every 15 days) and oral delivery of risedronic acid (35 mg once per week), for the treatment of osteoporosis. The patient underwent an accurate clinical evaluation. At the objective examination, facial asymmetry, crepitation of the mandible bony fragments and difficulty in mouth opening were observed. Extraoral clinical evaluation also revealed swelling and dull pain in the right mandibular side, right lip and chin numbness (Fig. 1A). Intraorally, she had an incomplete occlusion, partially rehabilitated with an upper mobile prosthesis (Fig. 1B). Soft tissue inspection showed pus draining, fistula and mucosal thickening on top of the lower alveolar ridge. Radiographic examination allowed us to identify a pathologic right mandibular body fracture (Fig. 1C). Bimanual palpation of the fracture site was performed and slight movement evoked. Clinical and radiographical features fulfilled the criteria for the diagnosis of stage 3 MRONJ, according to the AAOMS staging system [3].

The patient refused any type of surgical treatment. Therefore, the lack of excessive mobility, which indicated the presence of a stable fracture, suggested susceptibility of a conservative non-surgical approach. Specific informed consent was obtained. Medical treatment was then suggested with antiseptic mouth rinse (non-alcoholic chlorhexidine 0.12% at least 2 times a day) and systemic antibiotic administration with amoxi/clav 875mg/125mg (Augmentin, GlaxoSmithKline, Verona, Italy) 2 times a day and metronidazole 500 mg (Flagyl, Zambon, Vicenza, Italy) 3 times a day for 4 weeks. The patient was discharged with strict advice to maintain a liquid diet for 4 weeks, accurate oral hygiene, non-wearing of her dentures. A tight follow-up has been scheduled for the first 4 weeks. During follow-up visits, the focus was on swelling, pain, sensory deficits and on mucosa status. After one month, her symptoms diminished, and the intraoral fistula improved. Therefore, given the patient symptoms decreased, we have chosen to continue antibiotic therapy for another 4 weeks. Fortunately, she exhibited good adherence to the medical treatment and the follow-up was done at 2, 6 and 12 months.

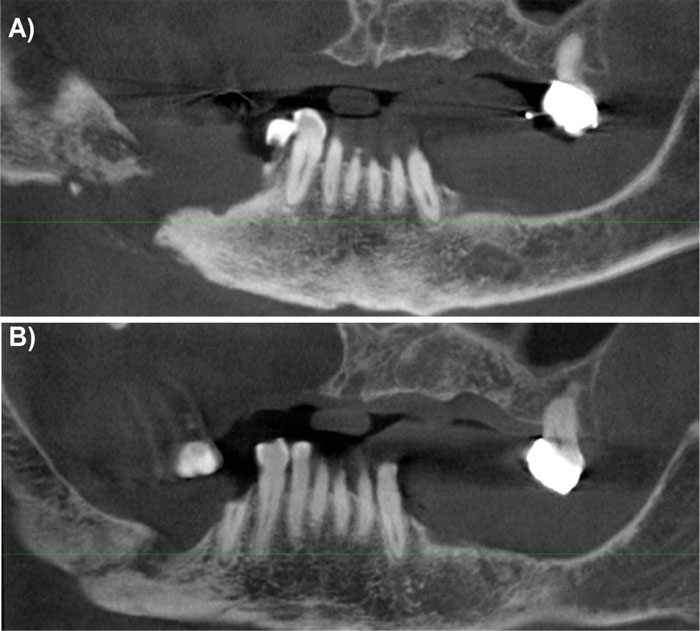

During the 6-month follow-up, a three-dimensional radiographic check through a Cone Beam CT was taken to evaluate the mandible condition and an initial spontaneous bone healing was seen compared to the initial situation (Fig. 2).

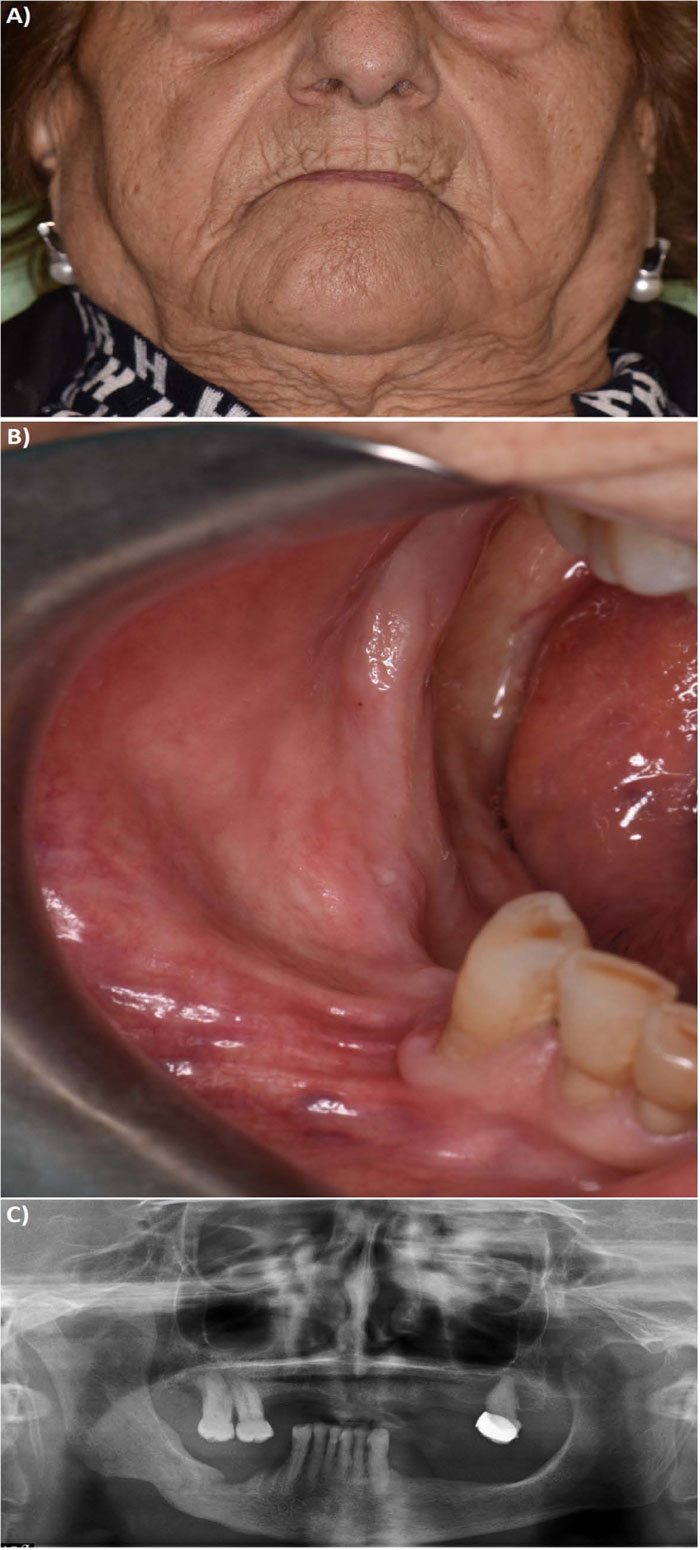

The 1-year follow-up visit revealed the healing of the mandibular fracture with bone regeneration, recovery of the mandible body continuity and bone callus formation (Fig. 3). The patient was functionally performing with a regular buccal opening, in the absence of any sensory deficits.

3. DISCUSSION

Osteoporosis is defined as a disease characterized by low bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue, leading to enhanced bone fragility and a consequent increase in fracture risk [11]. Treatment with BMAs reduces the risk of spontaneous fractures of postmenopausal osteoporosis through its influence on osteoclast-mediated bone resorption [12].

In the present case, an underlying pre-existing dental infection led to progressive mandibular necrosis in an osteoporotic patient treated with per os bisphosphonates for 4 years. Disease progression resulted in a pathological fracture of the mandible. Furthermore, the chin numbness was a warning sign of MRONJ, as previously described in the literature [13]. The patient’s reluctance to surgery obliged the authors to non-surgical management with antibiotic therapy and chlorhexidine mouthwash for two months with stable healing after one year of follow-up.

Prevention and control of the risk factors are fundamental to avoid MRONJ. Therefore, in order to establish a proper multidisciplinary approach in patients at risk, dental screening should be made an indispensable requirement for clinicians [3, 4, 8, 9].

According to the literature, there are robust evidences that an appropriate risk stratification of MRONJ based on dental procedure to be performed and dose, type and administration route of BMAs are essential. Usually, high-dose BMAs administered to cancer patients with metastases are associated with a higher risk of MRONJ development as compared to low-dose therapy given to osteoporotic patients. Furthermore, the risk of developing MRONJ after tooth extraction might be related to an underlying pre-existing periodontal infection rather than to the tooth extraction per se [8]. For patients taking BMAs per os for the treatment of osteoporosis, the risk of MRONJ is approximately 0.15% [14].

CONCLUSION

In the literature, there are some studies about the effect of BMAs treatment on fracture healing. A study by Tatli et al., evaluating the effect of zoledronate on mandibular fracture healing in a rabbit model, demonstrates that systemic administration of zoledronic acid accelerates and improves bone fracture healing in the maxillofacial region [15].

Although there is a reference position paper on the diagnostic, staging and treatment criteria of MRONJ [3], strategies for the prevention and management of this disease remain among the most discussed topics in the literature [1, 8, 9].

Recent literature reported that “best results for treating MRONJ grade III were achieved with an extensive bony resection up to the viable bleeding margins, with or without a microvascular flap reconstruction”, while conservative therapy alone would not be recommended, “except in patients that are ineligible for any kind of surgery” [10]. Complementary treatments to surgery, such as the use of autologous platelet concentrates, laser surgery, autofluorescence, ozone-therapy, hormonal therapy with teriparatide (only in osteoporotic patients) were studied to improve tissue healing and reduce recurrences [16-20].

To authors’ knowledge, this is the first case reported in the literature of successful non-surgical management of a mandibular fracture secondary to MRONJ with only systemic antibiotic therapy. This case report does not prove that non-surgical management could be the treatment of choice for stage III MRONJ, but our result could arouse great interest. It is also important to underline the correlation between the failure to adopt preventive measures and MRONJ. A review of the AAOMS classification has been suggested by several authors [1, 8]. Indications for intake, time and route of administration of BMAs should be considered in the classification of MRONJ patients. In addition, new guidelines are needed to indicate dental treatments to be performed as primary prevention in patients before, during and after the BMAs administration.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| BMAs | = Bone-Modifying Agents |

| MRONJ | = Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw |

| AAOMS | = American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Not applicable.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

Not applicable.

STANDARD OF REPORTING

CARE guidelines and methodology were followed.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Specific informed consent was obtained.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [L.F], upon reasonable request.

FUNDING

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.