Dry Socket: Frequency, Clinical Picture, and Risk Factors in a Palestinian Dental Teaching Center

Abstract

Aims:

The objectives of this study were to find out the frequency, clinical picture, and risk factors of dry socket at the Dental Teaching Center of Al-Quds University in Palestine.

Methods and Materials:

Two previously used questionnaires were accomplished in this study over a one year period. The first questionnaire was completed for every patient who had one or more permanent teeth extracted in the Dental Surgery Clinic. The other one was completed for every patient suffered a postoperative pain and was diagnosed with dry socket.

Results:

There were 1305 dental extractions performed in 805 patients. The overall frequency of dry socket was 3.2%. The incidence of dry socket following non-surgical extractions was 1.7% while it was 15% following surgical extractions (P< 0.005). The incidence of dry socket was significantly higher in smokers (12%) than in non-smokers (4%) (P < 0.005), however, there is a strong association between the amount of smoking and the incidence of dry socket (P < 0.002). The incidence of dry socket was significantly higher in the single extraction cases (13%) than in the multiple extraction cases (5%) (P = 0.005). Age, sex, medical history, extraction site, amount of local anesthesia and experience of operator play no role in the occurrence of dry socket.

Conclusion:

Smoking, surgical trauma and single extractions are considered predisposing factors in the occurrence of dry socket. On the other hand, factors like: age, sex, medical history, extraction site, amount of anesthesia, and operator experience have no effect on the observation of dry socket.

Dry socket is one of the most common complaints the patient suffers following dental extraction. It is more frequent following mandibular third molar extraction [1-7]. The literature shows variation in its incidence. Petri and Wilson (1992) [8] reported a 0% incidence while Erickson et al. (1960) [9] reported an incidence of 35%. Dry socket occurs due to the disintegration of the blood clot by fibrinolysis [10]. Many factors contribute to the occurrence of dry socket. For example: low experience level of operator [2, 6] preoperative infection [10, 11], sex [10, 12], site of extraction [6, 12], use of oral contraceptives [13], smoking [14], and use of local anesthetics with vasoconstrictor [15]. The incidence of dry socket can be reduced through the use of antibiotics [16,17], antifibrinolytic agents [18], mouthwashes [19-21], steroids [22] and intra-alveolar medicaments [7]. The management of dry socket includes reassurance of the patient, irrigation, and placement of intra-alveolar dressing [9, 22-24].

This is the first study of dry socket at the Dental Teaching Center of Al-Quds University in Palestine. Its aims were to find out the frequency, clinical picture and risk factors at this Palestinian dental teaching center.

It does worth to mention that this study was totally observational without any interference with any of the clinical procedures normally followed at this center.

Description of the Study

During this study, 1305 permanent tooth extractions were performed in 805 patients. There were 467 (58%) male patients and 338 (42%) female patients. The age of patients ranged from 10 to 73 years with a mean of 35.4 (± 14.95) years.

The Dental Teaching Clinics of Al Quds University was the setting of the study. These Clinics are located in Abu Dies besides Eastern Jerusalem in Palestine (West Bank), and are involved in the training of undergraduate dental students. It serves the community of Eastern Jerusalem and its neighboring towns and villages, which have a total population of around 500,000.

The study was totally observational, without any interference with treatment protocols followed at the dental teaching Clinics of Al Quds University.

Data were collected over a period of 16 months, from October 1st 2006 to January 28th 2008 using two questionnaires. The first one was completed for every patient who had one or more permanent teeth extracted in the Dental Surgery Clinic. Patients who had only deciduous teeth extracted were excluded from the study. The questionnaire was filled by the person who did the extraction. It included items such as patients' personal data, smoking habits, medial history and medications, teeth extracted indication for extraction, level of experience of the operator who performed the extraction, amount and technique of local anesthesia, and postoperative medications. Features of third molar also recorded (Fig. 1).

Dry sockets at the Dental teaching Hospital Extraction sheet.

The other one was completed for every patient suffered a postoperative pain and was diagnosed with dry socket. According to Blum's definition of dry socket [22], patients were diagnosed with a dry socket if they had at least two of the following signs and symptoms:

- Empty socket

- Pain in or around the socket within one week of the extraction

This questionnaire also included patients' personal data, socket affected, signs and symptoms, onset of symptoms, and given treatment (Fig. 2).

Questionnaire used for subjects with a dry socket.

Data were analyzed using SPSS® for Windows (Version 9; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) and Epi-info® (CDC, Atlanta, GA, USA) statistical software. Descriptive statistics and bi-variant data analysis using chi-square tests were done as appropriate. P value was set at 0.05 as level of significance.

RESULTS

During the study period, 1305 dental extractions were carried out in 805 patients. There were 467 (58%) male patients and 338 (42%) female patients. Age of patients ranged from 10 to 73 years with a mean of 35.4 (±14.95) years.

A total of 286 (35.5%) patients were smokers, of whom 33 (7% of the total sample) were heavy smokers (smoked more than 20 cigarettes per day). The proportion of smokers was noticeably higher in the male group than in the female group (58% and 3.9% respectively). Despite most of patients 566 (70.3%) were fit and healthy at the time of extraction, 239 (29.7%) had varying underlying systemic conditions (Table 1), and 169 (21%) were taking different medications (Table 2).

Summary of the Medical History of the Study Population

| Medical History | Number of patients | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| None | 566 | 70.3 |

| Diabetes Mellitus (DM) | 25 | 3.1 |

| Hypertension (HT) | 19 | 2.6 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 5 | 0.6 |

| Asthma | 4 | 0.5 |

| DM and HT | 30 | 3.6 |

| Chronic Bronchitis | 15 | 1.9 |

| Previous Surgery | 30 | 3.7 |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 13 | 1.6 |

| Psychological disorders | 12 | 1.5 |

| Anemia | 5 | 0.6 |

| Peptic ulcer | 26 | 3.2 |

| Osteoporosis | 5 | 0.6 |

| Hepatitis | 21 | 2.6 |

| Renal stones | 10 | 1.2 |

| Hyperthyroidism | 3 | 0.4 |

| Epilepsy | 2 | 0.3 |

| Migraine | 11 | 1.4 |

| Prosthetic heart valve | 3 | 0.3 |

| Total | 805 | 100 |

Medications Used Regularly by the Study Population Before the Extraction

| Medication | No. of patients | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| None | 636 | 79 |

| NSAID’s | 25 | 3 |

| Paracetamol | 20 | 2.5 |

| Antihypertensive drugs | 18 | 2.2 |

| Hypoglycemic agents | 15 | 1.9 |

| Warfarin | 20 | 2.5 |

| Salbutamol | 5 | 0.6 |

| Antidepressant drugs | 7 | 0.9 |

| Sodium valproate | 8 | 1 |

| Oral contraceptives | 25 | 3.1 |

| Insulin | 18 | 2.3 |

| H2-blockers | 5 | 0.6 |

| Ferrous sulphate | 3 | 0.4 |

Upper anterior teeth and posterior teeth constituted 217 (16.7%) and 379 (28%) of the total number of extractions, respectively, whereas lower anterior teeth and lower posterior teeth constituted 198 (15.2%) and 510 (39.1%) of the total number of extractions, respectively. A total of 118 (91%) extractions were non-surgical (1046 (80%) simple elevations and 142 (10.9%) root separations), while 117 (9%) teeth needed surgical extraction (47 (3.6%) needed a flap with bone removal and 70 (5.4%) needed only a flap without bone removal).

Undergraduate students carried out 1158 extractions (88.7%), (347 (26.5%) by fourth year students, 811 (62.2%) by fifth year students), while clinical dental officers CDOs and consultants carried out 78 (6%) and 69 (5.3%) extractions (Table 3).

Distribution of Teeth According to the Operator

| Operator | No. of teeth | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 4th Year Student | 347 | 26.5 |

| 5th Year Student | 811 | 62.2 |

| Clinical Dental Officer | 78 | 6 |

| Consultant | 69 | 5.3 |

| Total | 1305 | 100% |

Advanced caries was the commonest cause of extraction leading to the extraction of 566 (41.2%). This was followed by periodontal disease which led to 314 (23.9%) extractions. In addition, pericoronitis and orthodontic treatment formed the indications for the extraction of 102 (7.9%) and 40 (6%) teeth, respectively. Only 30 (2.3%) teeth were extracted because of a missing opposing tooth (Table 4).

Distribution of Teeth According to the Cause of Extraction

| Reason for extraction | No. of teeth | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Advanced caries | 566 | 41.2 |

| Periodontal disease | 314 | 23.8 |

| Advanced caries and periodontal disease | 253 | 19.3 |

| Pericorinitis | 102 | 7.8 |

| Orthodontic treatment | 40 | 6 |

| Missing opposing tooth | 30 | 2 |

| Total | 1305 | 100% |

A total of 162 mandibular third molars were extracted, of which 32 (56.6%) were impacted and needed surgical extraction.

All teeth were extracted under local anesthesia. Infiltration around the tooth (labial/ buccal and lingual/ palatal) was used in 804 (56.1%) extractions, while regional block anesthesia (inferior dental/ lingual and mental block) was used in 501 (43.9%) extractions.

All patients received oral postoperative instructions by the operators. Post-extraction medications were prescribed for 192 patients. Pain killers (ibuprofen and/ or paracetamol) were prescribed alone for 97 patients, whereas a combination of antibiotics (either amoxicillin or metronidazole or both) and pain killers was prescribed for 95 patients.

Prevalence of Dry Socket

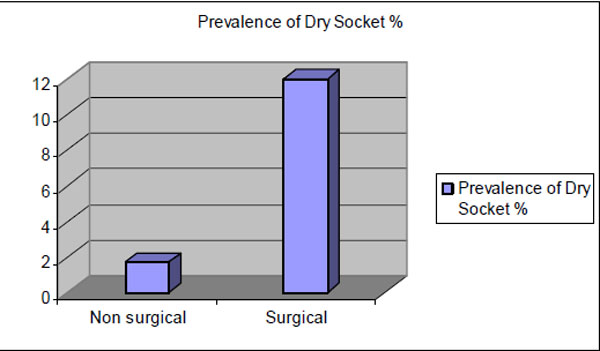

The overall incidence of dry socket was 3.2% (40 dry sockets in 1305 extractions). Some patients developed more than one dry socket, which made the overall incidence per patient 6.4% (30 patients with dry sockets out of 469 patients who had extractions). In addition, dry socket incidence (per tooth) following non-surgical extraction of teeth was 1.7 % (20 of 1188), while that following surgical extraction was 12% (14 of 117). This difference was statistically significant (p< 0.002) (Fig. 3).

Distribution of dry socket prevalence according to surgical vs non surgical extraction.

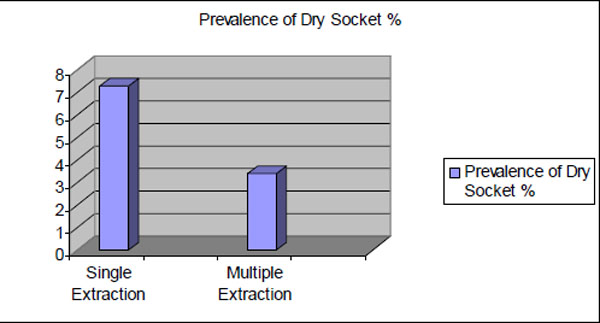

Patients were grouped into single-extraction cases (302) and multiple extraction cases (167). The incidence of dry socket in the first group was 7.3% (22 of 302), while in the second group it was 3.4% (18 of 536). This difference was statistically significant (P = 0.018) (Fig. 4).

Prevalence of dry socket following single and multiple extractions.

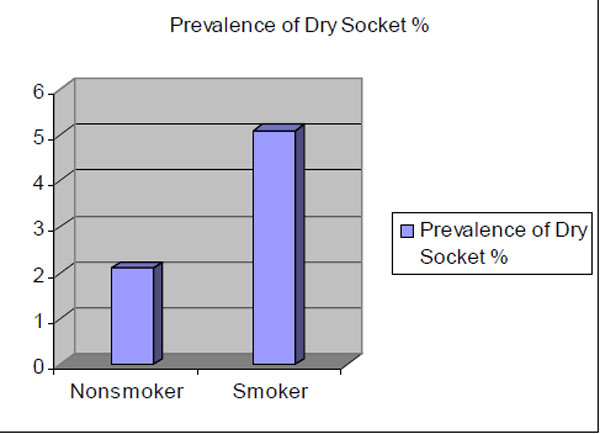

The incidence of dry socket was 5.1% (23 dry sockets in 422 extractions) following extractions in smokers compared to 2.1% (17 dry sockets in 833 extractions) in non-smokers. This difference was statistically significant (P= 0.001) (Fig. 5).

Prevalence of dry socket in relation to smoking.

There was no statistically significant association between the development of dry socket and patient's age, sex, medical history, medications (preoperative or postoperative), indications for extraction, operator experience, and amount and technique of local anesthesia.

Patients who developed dry socket were 16 (53%) males and 14 (47%) females. The incidence of dry socket in female patients was 3.9% (14 dry sockets in 359 extractions) compared to 2.5% (26 dry sockets in 1040 extractions) in male patients. This difference was statistically insignificant (p=0.671).

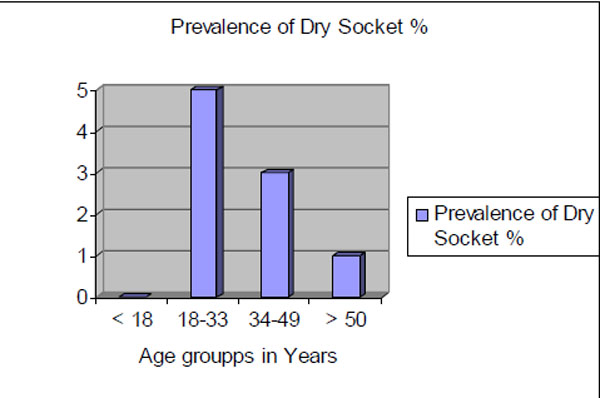

The peak incidence of dry socket was in the 18 to 33 year age group and was 4.8 % (21 dry sockets in 438 extractions) compared to 2.9% (7 dry sockets in 241 extractions) in patients whose ages ranged from 34 to 49 years and 1.6% (12 dry sockets in 750 extractions) in patients who were older than 50 years. None of the patients under 18 years of age developed dry sockets. This difference was statistically insignificant (p= 0.201) (Fig. 6).

Distribution of dry socket incidence in different age groups.

Regarding surgical technique and surgical experience, the incidence of dry socket was found to be 1.8% (21 of 1167) and 1.2 % (1 of 83) following non-surgical extractions performed by undergraduate and postgraduate students, respectively. This difference was statistically insignificant (p= 0.677).

DISCUSSION

Dry socket is an important clinical complication. It is characterized by severe pain starting after two or three days of extraction. The etiology of this complication is an increased local fibrinolysis leading to breakdown of the clot [10]. Some antifibrinolytic agents, when placed topically in the extraction site, have been shown to reduce the occurance of dry socket [25]. Surgical trauma and bacterial infections remain the acceptable initiating factors of this fibrinolytic activity [10].

The results of this study show the prevalence of dry socket at the Dental Teaching Center/ Al-Quds University and its clinical features are generally similar to those reported in the literature. The overall prevalence of dry socket was 3.2%.

The increase in extraction difficulty leads to increase in the prevalence of dry socket [10, 12, 22]. This is attributable to more liberation of direct tissue activators secondary to bone marrow inflammation following the more difficult and, hence, more traumatic extractions [10]. In the current study surgical extractions were associated with a significantly higher incidence of dry socket (12%), which supports what is documented in the literature in which trauma is considered as a contributing factor in the pathogenesis of dry socket.

Single versus multiple extractions is considered a factor that increases the prevalence of dry socket. Previous studies [4, 12] showed the prevalence of dry socket was higher after single extractions than multiple extractions, and this was consistent by the results of the current study in which dry socket prevalence was 7.3% following single extractions and 3.4% following multiple extractions. Multiple extractions are generally simple because they are performed on mobile and periodontally compromised teeth. Krough [26] recommended if several adjacent teeth are to be extracted, it is better to perform in one operation.

In this present study the difference in the prevalence of dry socket between males (2.5%) and females (4.3%) was statistically insignificant. This finding coincides with the study perfomed by Al Khateeb et al. [11] and contradicts the results of several studies [3, 4, 12, 27]. MacGreoger12 reported a higher incidence of dry socket in females with a male: female ratio of 2:3. The possible explanation of this difference can hide behind the fact that eastern societies differ from western ones in smoking habit between females and males. In western societies females smoke in a higher percentage than in eastern societies. The present study shows that the percentage of of female smokers was much less than males (3.4% and 58% respectively).

It is worth mentioning that the use of oral contraceptives is a factor the raises the prevalence of dry socket among female patients. The use of contraceptives thought to be the reason behind the increased susceptibility of females to dry socket [1, 24, 27] was minimal in this study. However, timing of dental extraction according to menstrual cycle is a predisposing factor in the occurrence of dry socket [28].

The results of this study also showed the prevalence of dry socket to be highest in third and fourth decades of life with a peak incidence in the 18-33 year age group which is in agreement with results of many researches [3, 4, 6, 11, 12]. The possible explanation for this age dependence is still unknown, but the presence of well developed alveolar bone and the relative infrequency of periodontal diseases at this age (both make tooth extraction more difficult) may provide a possible explanation.4 Most surgical extractions in this study were performed in this age group, and surgical extractions are associated with a higher incidence of dry socket.

The results of this study contradicts the findings of Johnson and Blanton, [29] who showed no significant difference in the prevalence of dry socket between smokers and non-smokers, a dose dependent relationship between smoking and the occurrence of dry socket was demonstrated in the present study which is similar to the findings of other studies [14, 30].

Failure to follow postoperative instructions is behind the increased prevalence of dry socket among smokers. It has been reported patients who smoked on the same day of surgery had a higher incidence of dry socket than those who smoked on the second day postoperatively [30]. Whether a systemic mechanism or a direct local effect (heat and suction) on the extraction site is responsible for this increase in the occurrence of dry socket is unclear.

CONCLUSIONS

From the results of this study, the following conclusions can be made:

- The incidence of dry sockets following single extractions was significantly higher than that following multiple extractions.

- There was a statistically significant difference in the incidence of dry socket between smokers and nonsmokers.

- The incidence of dry socket was higher following surgical extractions than following non-surgical extractions.

- There was no statistically significant association between the development of dry socket and patient's age, sex, medical history, medications (preoperative or postoperative), indication for extraction, extraction site, and operator's experience.