Factors Influencing the Decision Process within Seeking Orthodontic Care among the Saudi Population: A Cross-sectional Survey

Abstract

Aims & Background

Orthodontic treatment is the first choice for the treatment of many different types of malocclusions, and patients’ decision processes while seeking orthodontic treatment are multifactorial. The aim of the present study is to assess these factors influencing the decision process regarding the public and orthodontic treatment for themselves or for their children, as well as the factors influencing the selection of an orthodontist versus a general dentist in Saudi Arabia.

Materials and Methods

A survey-based questionnaire was distributed through social media accounts that included questions about demographic data, reasons for seeking orthodontic care, barriers to care, and sources of information that may influence the decisions regarding the choice of orthodontic treatment for the participants and their children.

Results

The final sample included 320 responses from eligible participants (181 men & 139 women with a mean age of 39.98). ‘Family dentist recommendation’ was the most important reason for participants to seek out orthodontic treatment for themselves or a child while finding a caregiver who can handle complications and the availability of appointments were the most important barriers in seeking orthodontic treatment. Participants also assumed an orthodontist would be more reliable in finishing the treatment in the expected duration, yet they expected that treatment with a general dentist would be less costly and more convenient.

Conclusion

A referral from the family dentist has the most impactful influence on seeking orthodontic care. People are keen to have their treatment done by an orthodontist, but the major barrier in seeking orthodontic care is finding a suitable candidate. Parents prioritize orthodontic treatment for their children more than for themselves.

1. INTRODUCTION

Malocclusions may be defined as any deviation from the normal alignment of teeth and/or their occlusal relationships beyond what is accepted to be normal [1]. Epidemiological studies by the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that malocclusion is considered a public health problem with a high prevalence in most countries [2, 3]. Globally, the prevalence of malocclusions ranged from 48% to 81% among children and adolescents [4]. A recent systematic review in Saudi Arabia reported that different traits of malocclusions have affected a high number of Saudi individuals, with Angle’s class I malocclusion being the predominant type (69.66%), while the nation also has a higher prevalence of Class III malocclusions (12.5%) than what is reported in other populations [5, 6].

While orthodontic treatment is the first choice to treat different types of malocclusion, the decision processes in seeking orthodontic treatment are multifactorial [7]. Patient’s background factors include gender, age, educational level, socioeconomic status, the severity of the malocclusion, level of dental care, and self-esteem of facial aesthetics affecting the patient’s desire for pursuing orthodontic treatment, as well as their attitude towards orthodontic care [8]. Referrals from a general dentist to seek orthodontic treatment have been reported as a major influence on seeking orthodontic care [9]. Improving the appearance and, to a lesser extent, the occlusal functions were also reported to be reasons that individuals seek orthodontic care [10, 11]. Among Saudis, factors related to the nature of orthodontic treatment, such as the cost, duration of treatment, and accessibility to care, were reported to be of a significant influence on treatment decisions [12, 13]. Therefore, a greater understanding of these factors in the context of clinical orthodontic practice is important on many fronts since it enables a better planning of resources, assessment of treatment needs and patient expectations in order to provide the best possible treatment outcomes [14]. This would increase the chance of patients’ cooperation, which is critical to the success of orthodontic treatment [15, 16].

Orthodontic treatment is ideally carried out by an orthodontist, yet the number of general dental practitioners (GDPs) who offer orthodontic care has been on the rise [17]. Patients seem to appreciate the extra qualifications needed for a GDP in order to become an orthodontist, but they are commonly unable to differentiate between an orthodontist and a GDP that performs orthodontic treatment [18]. There are several studies that have been conducted to assess the effectiveness of orthodontic treatment performed by orthodontists versus GDPs, but fewer studies have shed light on the influencing factors in the selection of a provider type by the patients [19].

Considering that only a few investigations have focused on this topic in Saudi Arabia, the aim of the present study is to assess factors influencing people’s decision process regarding the orthodontic treatment for themselves or for their children and factors influencing the selection of an orthodontist versus a GDP that performs orthodontic treatment among a sample of the adult population in Saudi Arabia. Since most of the similar previous studies in Saudi Arabia were conducted with a sample of patients already seeking dental treatment, this is the first attempt to conduct a survey on a sample of the general population in the country that focuses on the impact of different barriers to seeking orthodontic care for adult participants and how their perception of those barriers might change when seeking care for their children.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Design and Settings

This cross-sectional study is comprised of a self-administered survey that was made available online through a web-based survey tool, and the link was distributed through social media platforms. The period allocated to receive responses ranged from December 2022 to February 2023. The sex and gender equity in research (SAGER) guidlines were followed by the authors.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria and Sample Size

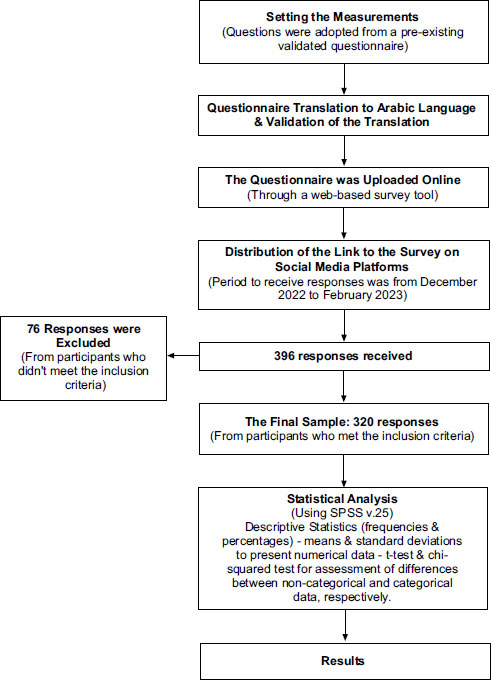

Adult subjects (18 years old and above) from both genders who are living in Saudi Arabia were included in the study. We used a convenience sample in this study, which meant that all the responses that were received from individuals who met the inclusion criteria during the time allocated to receive responses were included in the sample. Within that allocated time, 396 responses were completed, while 76 responses from subjects who did not meet our inclusion criteria were excluded from the sample. Thus, the final sample included 320 responses from eligible participants.

2.3. Measures and Ethical Approval

The questions were adopted from a validated questionnaire used previously in research conducted in the United States [20]. An Arabic translation of the questionnaire was prepared by one of the authors. For validation of the translation process, a back translation to the English language was prepared as a courtesy from an independent expert and was compared to the original questionnaire. The questionnaire was then divided into five sections: Section one is an introduction, with a detailed explanation of the study followed by consent for participation. Section two includes eight demographic questions about gender, age, education level, employment status, marital status, monthly income, and nationality. Both sections three and four consist of four similar questions to assess reasons for seeking orthodontic care, barriers to care for functional and appearance problems, and sources of information that may influence the decision of considering orthodontic treatment (section three regarding the participants themselves and section four regarding their children). A 4-point Likert scale of importance was used to answer questions in sections three and four as follows: not important at all (4), minor effect (3), important (2), and very important (1), indicating that lower scores reflect higher importance. The last section consisted of questions to assess the differences in perception of the participants toward general dentists and orthodontists performing orthodontic care, as well as their preference for a treatment provider. On average, it took participants about 12 minutes to complete the survey. Ethical approval was obtained from the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Umm Al-Qura University (Approval No. HAPO-02-K-012-2021-11-851).

2.4. Statistical Analyses

A Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 25) (IBM, Inc., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for the data analyses. Descriptive statistics were used as frequencies, percentages, medians, and ranges to present categorical data. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to assess the differences between categorical data. A value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Fig. (1) is a flowchart representing all the steps in the methodology of the study.

3. RESULTS

Out of the 320 participants, 181 (56.6%) were men, and 139 (43.4%) were women, with a mean age of 39.98 years and a standard deviation of 13.3. Almost all participants were Saudis (96.6%), and about two-thirds (63.1%) had obtained a bachelor’s degree from a college, while the vast majority were married (72.5%). Regarding employment, about half of the participants (54.7%) were reported to be employees, with 5.3% being free workers and about half of the participants having a monthly income below the 2018 national household income average of SR 11,984 per month [21]. Participants had different oral health care attitudes, with 39.4% of them reporting that they had a dental visit less than 6 months ago and 37.2% claiming they had not visited a dental office for more than a year. Only 12.2% of the participants attended the last dental visit for a regular check-up. About a third of participants had some form of orthodontic treatment either as children or adults, and about half of them were not interested in having braces, nor was it suggested to them. However, 62.2% of participants were open to having regular braces or clear aligners, depending on the need for either. The participants’ complete demographic data is presented in Table 1.

3.1. Reasons, Barriers, and Sources of Influence for Seeking Orthodontic Care

Participants considered that family dentist recommendations, and functional as well as, appearance concerns were the most important reasons to seek orthodontic care for themselves and their children. Possible correction without braces and pictures of beautiful smiles were regarded as less important than the above-mentioned reasons. With all the mentioned reasons, participants gave statistically significantly lower scores when answering the questions for their children compared to themselves (Table 2).

When considering possible barriers to seeking orthodontic care for both functional and appearance concerns, participants’ scores indicated that the cost of treatment, the time involved, finding a good caregiver, their confidence in the ability of the caregiver to handle possible complications, and the availability of appointments were the most important factors. Other factors, such as dedication to receive treatment and whether the cost of treatment is covered through insurance, were less important. Participants gave higher scores for barriers to seeking care for their children in comparison to themselves for all factors, except in relation to insurance coverage of treatment cost, but the only statistically significant difference was found in relation to dedicating time for treatment when the concerns were about appearance (Table 2).

Our results revealed that the referral from the participants’ own dentist was the most influential factor, then having their own dentist do the treatment, experiences of friends and recommendations from scientific societies. The least likely sources of influence on the participants’ decision were information from websites and other forms of advertising. The participants’ scores when the questions were about their children were statistically significantly lower than scores when their own treatment was considered in relation to three factors: referral from their own dentist, having their own dentist do the treatment and recommendations from scientific societies (Table 2).

| Variables | Options | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 181 | 56.6 |

| Female | 139 | 43.4 | |

| The educational level | Elementary/intermediate | 7 | 2.2 |

| High school | 66 | 20.6 | |

| Bachelors | 202 | 63.1 | |

| Post-graduate | 45 | 14.1 | |

| Employment status | Currently a student | 42 | 13.1 |

| Employee | 175 | 54.7 | |

| Free worker/self-employed | 17 | 5.3 | |

| Unemployed/retired | 86 | 26.9 | |

| The marital status | Single | 77 | 24.1 |

| Married | 232 | 72.5 | |

| Divorced | 7 | 2.2 | |

| Widow | 4 | 1.3 | |

| Monthly income by SR | Less than 5000 | 63 | 19.7 |

| 5000-10,000 | 93 | 29.1 | |

| 10,000-15,000 | 75 | 23.4 | |

| More than 15.000 | 89 | 27.8 | |

| Nationality | Saudi | 309 | 96.6 |

| Non-Saudi | 11 | 3.4 | |

| Last dental visit | Less than 6 m | 126 | 39.4 |

| 6m-1y | 75 | 23.4 | |

| More than 1y | 119 | 37.2 | |

| The reason for the last dental visit | Caries removal | 75 | 23.4 |

| Scaling | 75 | 23.4 | |

| Dental pain | 79 | 24.7 | |

| Check-up | 39 | 12.2 | |

| Orthodontic treatment | 20 | 6.3 | |

| Others | 32 | 10.0 | |

| Orthodontic treatment | Had care as a child | 26 | 8.1 |

| Had care as an adult | 79 | 24.7 | |

| Considering it | 63 | 19.7 | |

| Not interested | 152 | 47.5 | |

| Type of care preferred | Braces | 70 | 21.9 |

| Invisible “aligners” | 36 | 11.3 | |

| Either, if needed | 199 | 62.2 | |

| Both | 15 | 4.7 | |

| Care seeking | My parents | 20 | 6.3 |

| Family Dentist | 41 | 12.8 | |

| Family | 24 | 7.5 | |

| Friends | 18 | 5.6 | |

| My self | 72 | 22.5 | |

| No one | 145 | 45.3 |

| Factor | Adult | Child | P-value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Md | Min | Max | Md | Min | Max | ||

| Reasons to seek care | |||||||

| Family dentist recommendation | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | <0.001 |

| Functional concerns, physical problems | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | <0.001 |

| Appearance concerns | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0.002 |

| Pictures of beautiful smiles, ads | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0.005 |

| Possible correction without braces | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | <0.001 |

| Functional concerns | - | ||||||

| Out-of-pocket cost | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0.140 |

| Insurance, good payment plan | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0.277 |

| Time involved with treatment | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0.461 |

| Busy, other things going on in my life | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0.056 |

| Finding a good person to give care | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0.167 |

| Certainty complications will be handled | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0.888 |

| Availability, can I get an appointment | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0.398 |

| Appearance concerns | - | ||||||

| Out-of-pocket cost | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0.641 |

| Insurance, good payment plan | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0.187 |

| Time involved with treatment | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0.698 |

| Busy, other things going on in my life | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0.003 |

| Finding a good person to give care | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0.305 |

| Certainty complications will be handled | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0.572 |

| Availability, can I get an appointment | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0.755 |

| Sources of influence | - | ||||||

| Referral from own dentist | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | <0.001 |

| Having own dentist do the work | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0.022 |

| Stories, experiences of friends | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0.683 |

| Online (Web) information | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0.326 |

| Other advertising | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0.157 |

| Dental Society, specialty recommendations | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0.009 |

3.2. Perceptions regarding Treatment by an Orthodontists versus a GDP

Participants expected a more expensive treatment by an orthodontist, with 40.6% assuming orthodontists would charge 3000 – 8000 Saudi Riyals (SR), and 55.3% assuming the cost of treatment with a GDP would be less than 3000 SR. When asked about the overall duration of treatment, 44.5% of the participants expected a year to a year and a half for an orthodontist, and only 37.5% thought GDP would finish treatment in the same duration. Regarding the convenience of appointments, location and working hours, higher percentages of participants thought that it was easier when treatment was provided by a GDP rather than an orthodontist. It was also found that 60.3% of participants assumed a positive reputation would be for an orthodontist and only 35.9% for a GDP, while almost 78% of participants thought that an orthodontist would reliably distinguish difficult from easy cases, with only 31.6% assuming the same for a GDP. Participants’ positive perceptions towards orthodontists were highly statistically more significant than their perceptions towards GDPs, except about the ability to assess the difficulty of the cases, where there was no statistically significant difference.

| Factor | Options | Ortho* (%) |

GDP** (%) |

P-value*** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | Less than 3000 SR | (21.3) | (55.3) | <0.001 |

| 3000-8000 SR | (40.6) | (31.9) | ||

| 8000-12000 SR | (26.9) | (10.9) | ||

| More than 12000 SR | (11.3) | (1.9) | ||

| Duration of treatment | 6 months – 1 year | (34.7) | (36.6) | <0.001 |

| 1y-1.5y | (44.7) | (37.5) | ||

| 1.5y-2y | (20.6) | (25.9) | ||

| Convenient appts, location, hours | Very easy | (30.6) | (33.2) | <0.001 |

| Fine | (47.5) | (50.0) | ||

| Difficult | (21.9) | (16.9) | ||

| Reputation, previous relationship | Known comfortable | (60.3) | (35.9) | <0.001 |

| Assumed | (34.1) | (52.5) | ||

| I will overlook doubts | (5.6) | (11.6) | ||

| Reliably distinguish easy or difficult cases | Knows and tells me | (77.8) | (31.6) | 0.118 |

| Probably knows | (20.0) | (40.9) | ||

| Unsure, may conceal | (2.2) | (27.5) |

** General Dental Practitioner.

***Significant at P< 0.050.

| Factor | Options | Ortho* (%) |

GDP** (%) |

P-value*** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Certainty of 100% successful outcomes | Positively | (57.8) | (19.4) | <0.001 |

| Hopeful | (40.0) | (50.0) | ||

| A little doubt | (2.2) | (30.6) | ||

| Ability to manage all complications | Positively | (60.9) | (23.1) | <0.001 |

| Hopeful | (36.6) | (48.1) | ||

| A little doubt | (2.5) | (28.7) | ||

| Promises more than can be delivered | Positively | (60.3) | (21.9) | <0.001 |

| Hopeful | (38.8) | (54.4) | ||

| A little doubt | 0.9 | 23.8 | ||

| Functional case (bad bite) | Strong choice | 73.4 | 19.1 | <0.001 |

| Lean toward | 18.1 | 33.8 | ||

| Depend on details | 8.4 | 47.2 | ||

| Appearance case | Strong choice | 70.6 | 20.6 | <0.001 |

| Lean toward | 19.7 | 31.9 | ||

| Depend on details | 9.7 | 47.5 | ||

| Both function and appearance | Strong choice | 76.9 | 20.0 | <0.001 |

| Lean toward | 15.9 | 31.3 | ||

| Depend on details | 7.2 | 48.8 | ||

| Expect the case to be complex | Strong choice | 79.4 | 19.7 | <0.001 |

| Lean toward | 14.4 | 27.8 | ||

| Depend on details | 6.3 | 52.5 |

** General Dental Practitioner

***Significant at P< 0.050.

Regarding the expectations of treatment outcomes, 57.8% of participants were certain that an orthodontist would be able to successfully finish the treatment, while 50% were hopeful that this would be the case under the care of a GDP. Moreover, about 60% of participants were positive that orthodontists would keep their promises about the treatment results and be able to manage complications if they arose, and 24% to 28% were skeptical about those expectations in the case of GDPs. Regarding their preferences for a treatment provider, the majority of participants strongly chose an orthodontist for all kinds of cases. For all the previous factors, differences were highly statistically significant (Tables 3 and 4).

4. DISCUSSION

In this cross-sectional study, our aim was to assess possible factors that might influence people in Saudi Arabia to seek orthodontic care for themselves and their children. We also attempted to have a better understanding of what might be the possible reasons for patients to consider treatment by an orthodontist or a GDP. Furthermore, we explored differences in people’s perceptions and expectations of treatment carried out by an orthodontist vs GDP. The importance of such a study is to give the decision-makers in the country a better view of how the public perceives orthodontic treatment and how they process information that influences their decision to pursue care in order to be able to tailor a healthcare policy that better addresses the needs and expectations of people living in Saudi Arabia.

According to this survey, one of the most influential factors in considering orthodontic treatment for one’s self or child is the family dentist recommendation. The significant rule of GDP in referring patients for orthodontic treatment has been reported previously [22], which reflects people’s confidence in their caregiver’s opinion above all other factors [20]. Therefore, a GDP should have sufficient knowledge and understanding of malocclusion and be able to identify orthodontic problems in order to refer the patients to a specialist. However, previous studies have reported insufficiencies in orthodontic knowledge in clinical situations among GDPs and recommended further orthodontic continuous education for GDPs and non-orthodontic specialists [23, 24].

Whether the concern was for function or appearance reasons, finding a good caregiver who can certainly handle complications and the availability of appointments were major barriers to seeking orthodontic treatment for one’s self or a child. This might be explained by the scarcity in the number of orthodontists in Saudi Arabia. According to Saudi Arabia’s General Authority of Statistics, the population is 32.28 million as of 2022 [25], while the most recently available data about the dental workforce reports that the number of registered orthodontists in the country is 573, most of whom are practicing in major cities [26]. This low orthodontist to population ratio, and with most orthodontists being based mainly in major cities, probably has created a supply and demand gap, as well as uneven access to orthodontic care for the public. Another major barrier to seeking orthodontic treatment was the out-of-pocket cost. Other previous studies in Saudi Arabia that explored possible barriers to orthodontic care also reported that the expected high fees were the most significant barrier to receiving treatment.

Participants from this survey reported a higher influence from reliable sources of information on whether there is a specific need for orthodontic care for themselves and their children rather than mass advertisements and general information on websites. A referral from their own dentists, and preferably that the treatment is carried out by them, have the highest influence. Park et al. in their study also reported that most individuals who underwent orthodontic treatment in an orthodontic clinic were referred by a GDP, and most of those who received orthodontic treatment by a GDP had their family general dentist do the treatment for them [17]. This could be explained by the existence of a trusting relationship, as well as the high convenience of being treated by their GDP rather than seeking treatment somewhere else. Information from official scientific societies also has had a great influence on decisions regarding orthodontic care. This reported hierarchy of different factors influencing individuals’ orthodontic treatment might contradict other views. There is growing evidence suggesting that advertisements on social media accounts and the presence of dentists on different social media platforms have an obvious positive impact on attracting new patients to their dental practices [27]. However, the subjects that participated in those studies were recruited from pools of patients already in the process of receiving dental care, not individuals who either were still not aware or had doubts about their need for treatment. Nevertheless, the rule of GDP in suggesting treatment for individuals in need of orthodontic care and referring them to orthodontic clinics seems to be dominant [20].

Participants expected that a specialized orthodontist would charge more than a GDP and that an orthodontist would finish cases in a shorter duration. Although participants expect both an orthodontist and a GDP to be able to distinguish easy from difficult cases, they have a higher preference for being treated by an orthodontist regardless of whether they sought treatment for functional or appearance reasons. Moreover, they were more confident that an orthodontist would be in being able to deliver all treatment goals and manage complications, if they may arise, properly. This reflects a high awareness of the participants regarding the impact of specialty training and experience on the quality of care provided. These findings are in accordance with a recent study conducted in 2020 investigating the public perception of the differences between specialist orthodontists and GDPs who provide orthodontic treatments in Australia and Sweden, and the authors reported that most participants believed an orthodontist would be more reliable in providing orthodontic treatment [27]. Even though there has been an increasing number of choices for the public to get orthodontic treatment by non-specialists, the confidence in the high quality of care provided by orthodontists seems to also be a trend in other populations [19].

The results of this study show that parents (or future parents) are prioritizing orthodontic treatment for their children whenever there is a need for it. They are also willing to dedicate more time to such a task than when they think about having orthodontic treatment for themselves. This may indicate that even though parents are willing to accept some degree of malocclusion, they are more concerned about addressing the orthodontic needs of their children. It has been reported that the parent’s sense of responsibility, the importance of timing of treatment to prevent future complications, and the perceived esthetic, as well as the social benefits of orthodontic treatment, are all factors that motivate parents in seeking orthodontic treatment for their children. Therefore, reportedly, some parents may believe that it is more socially acceptable for children to have braces than it is for adults [19]. What we predict from this is that, even though there is an increasing number of adults seeking orthodontic treatment, children will continue to form the majority group among patients visiting orthodontic practices.

This study has several strengths, such as using a questionnaire that was previously tested for validity. Also, this study is one of only a few similar studies conducted in Saudi Arabia investigating this topic. However, there were some limitations, including a convenience sample and a self-administered questionnaire.

Considering our results, it is of great emphasis to implement the interdisciplinary knowledge related to orthodontic treatment needs and referral timing as a part of the continuous education programs tailored for general dentists. Healthcare authorities in the country are advised to implement public educational campaigns to raise awareness regarding different aspects of orthodontic treatment. Furthermore, there is a need to lay out plans that promote better access of individuals to orthodontic care. Finally, further research is needed to explore the ability of the public in Saudi Arabia to distinguish between a qualified orthodontist and a GDP who provides orthodontic treatment.

CONCLUSION

Based on the results of this study, we can conclude that there is a high awareness among the Saudi population regarding the quality of orthodontic care provided by an orthodontist. A referral from the family dentist is the most impactful influence on an individual’s decision to seek orthodontic care. Regardless of the reason to seek orthodontic treatment, people are keen to have the treatment done by an orthodontist than by a general dentist. The major barrier in seeking orthodontic care is finding a specialist in the field. Finally, parents and future parents are prioritizing orthodontic treatment for their children rather than for themselves.

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE

The outcomes of this study demonstrate the central rule of general dentists and family dentists in the referral of patients to orthodontic clinics. Therefore, we advise orthodontists to work closely with general dentists and family dentists for the effective referral of potential orthodontic patients.

Investing in improving the knowledge of general dentists about malocclusion is important for them to be able to identify individuals who are in need of orthodontic care.

Orthodontic practices should utilize information about malocclusions and orthodontic treatment approved by scientific societies rather than general advertisements, as it is more impactful on patients’ decision to undergo orthodontic treatment.

Despite the growing number of adults demanding orthodontic care, children will continue to form the majority group visiting orthodontic practices.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| GDP | = General dental practitioner |

| WHO | = World Health Organization |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Ethical approval was obtained from the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Umm Al-Qura University (Approval No. HAPO-02-K-012-2021-11-851).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals were used in this research. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committees and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.