All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic on Dental Care of Babies and Children

Abstract

Objective

To evaluate parents' attitudes toward their children's dental care and habits during the early and intermediate stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil.

Material and Methods

A structured online questionnaire containing 22 questions (available from August 19th to September 18th, 2020) was used. The parents of babies and children (aged 0-6 years) who were visiting the Baby Clinics of the Dental Department were eligible to participate in this study.

Results

During the stay-at-home orders, only 21.1% of the parents continued to take their child to the pediatrician for routine follow-up; 22.6% took the children to the doctor only due to an emergency. Most parents (53.5%) reported being very afraid of going out with their babies/ children during the pandemic and became infected. Most parents (84.9%) reported having doubts about maintaining their baby/child’s oral health guidelines during quarantine, and 81.1% had doubts about what to do in case of eruption of their baby/ child’s teeth. Some parents reported a decrease in the oral hygiene and eating habits of their babies/ children during the pandemic. The parents with a reduced income reported a significantly greater reduction in oral hygiene habits.

Conclusions

During the early and intermediate stages of the pandemic, when stay-at-home orders were suggested, parents of children aged 0-6 were afraid to take their children to medical and dental appointments. Besides that, these caregivers also claimed that their family routines of food and oral hygiene were altered.

1. INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus outbreak, which causes the disease known as COVID-19, began in late December 2019 in Wuhan, China. After two months, the World Health Organization (WHO) classified the COVID-19 as a pandemic. The risk assessment configures the disease as a high global risk. Worldwide, there are more than 32 109 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 and almost 2,5 million deaths, according to the WHO [1]. Brazil is one of the epicenters of the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the low testing rates, as of February 11, 2021, there are more than 9 million confirmed cases and 206,301 cumulative deaths, with strong evidence of underreporting cases [2].

In the early stages of the pandemic, infection control measures were requested from all authorities globally to prevent the spread and help the virus [3]. Among the strategies used are conducting diagnostic tests for COVID-19, extreme social isolation, localized quarantines and monitoring of the most vulnerable population [4].

In the early and intermediate stages of the pandemic, when this survey was conducted, in many Brazilian municipalities, dentists were not allowed to perform elective dental care. Dental care was restricted to dealing with urgent situations and emergencies. In other places, only social isolation was recommended. However, dentists can still perform non-elective appointments, taking some extra precautionary measures and following the recommendations of the Federal Council of Dentistry and the National Dental Associations [5]. Since the coronavirus can be easily contracted by contact with infected secretions and aerosols, and due to the characteristics of dental care environments, the risk of cross-infection can be high among patients and dentists [6]. Moraes et al. [7] showed that the work status for Brazilian dentists was affected by 94%, with less developed regions being more impacted. Besides, a recent study [8] showed that the COVID-19 pandemic affected the number of pediatric dental procedures carried out in Primary Health Care in Brazil and also strongly and negatively impacted the pediatric treatments carried out in the Brazilian Public Health System. However, little is known about private pediatric dental care.

Campagnaro et al. [9] assessed the impact of the pandemic on fear, dietary choices and oral health perceptions of parents of children aged 0–12 years and found that most families have experienced changes in daily routine and eating habits during the pandemic. Parents fear COVID-19 and it impacts their behavior regarding seeking dental care for their children [9].

Amid this uncertainty in the pandemic, some patients and family members have been unsure whether or not to attend routine medical and dental appointments. It is important to assess baseline parameters related to primary dental care (educational/ preventive) for babies and children under six years of age so that it could be possible to plan medium long-term actions to respond to the challenges facing the pediatric dental sector related to the COVID-19 pandemic [7].

So, the objective of this study was to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the dental care of babies and children under 6 years of age, as well as to describe the feelings of those responsible for the care. In addition, we also evaluated the change in family income during the pandemic and the impact that this brought on the child's food routine.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

This was a cross-sectional, exploratory, descriptive observational study with a quantitative approach. The survey's objective was to address key questions that could impact the primary pediatrician dental sector in Brazil as the country was a new pandemic epicenter.

The representative sample size was estimated using a 95% confidence level and a margin of error of 5%. The sample calculation considered 10,100 children aged 0–12 years in the city of Arapongas, Paraná, Brazil. The sample size was estimated at a minimum of 300 respondents.

A survey was created on Google Forms with 22 questions and sent to 400 parents of babies and children under 6 years of age participating in the Preventive Dental Program in the municipality of Arapongas, Brazil, via WhatsApp Messenger App (WhatsApp Inc., California, EUA), obtaining a return of 318 questionnaires. Those responsible were randomly chosen from among the Program participants after authorization from the competent municipal agents and approval by the Ingá University Center Uningá Research Ethics Committee (CAEE 35713220.6.0000.5220). The contact (sending the invitation and link) to those responsible was made by one of the researchers, a dentist who participates in this Preventive Dental Project. The questionnaire was available online from August 19th, 2020, to September 18th, 2020.

The Preventive Dental Program in the municipality of Arapongas, Brazil, attends babies and children aged 0-6 years, offering guidance to parents on preventing tooth decay, diet, non-nutritive habits, fluoride therapy, applying sealants when indicated, and, if necessary, also performing curative treatment. Appointments are scheduled every 3 months.

The individuals participated voluntarily; the research was anonymous and confidential, and when answering it, the parents would agree with their participation after signing the informed consent terms. The survey comprised questions about social demographic information, the impact of the pandemic on medical and dental care habits, the impact on oral health care and eating habits, and the impact on family income (Table 1).

The answers were obtained and tabulated in Excel for statistical analysis, which involved the descriptive, number, and percentage responses. Associations between the answers were performed with chi-square tests. The analyses were performed using the Statistica for Windows program (Statsoft, Tulsa, USA), adopting a 5% significance level.

Table 1.

| Social Demographic Information | 1. Do you agree to participate in this survey? | ||||||

| 2 . How old are you? | |||||||

| 3. Sex () Male () Female | |||||||

| 4. How old is your baby/child (in months) who participates in the Children Preventive dental program? | |||||||

| 5. Have you ever taken the COVID-19 PCR test? () Yes () No |

|||||||

| 5.1. If your answer was yes to the previous question, have you tested positive for Covid-19? () Yes () No |

|||||||

| 6. How are you dealing with the quarantine and social distance restrictions? () I leave home for nothing () I am staying home as much as possible (going out only to buy food/medicine) () I am going out as usual |

|||||||

| 7. Do you work and/or study? If yes, how are your daily activities? () Yes, I am leaving home for work/study () Yes, but I am working/studying at home () I do not work or study |

|||||||

| 8. Considering the general anxiety level, how do you feel about the quarantine and the coronavirus pandemic? () Calm () Anxious () Fear () Panic () Indifferent |

|||||||

| Impact of the pandemic in medic and dental care habits | 9. During the early and intermediate pandemic stages, when quarantines and social isolation have been proposed, did you continue taking your baby/child to the pediatrician for routine appointment? () Yes () No () Only for emergency care |

||||||

| 10. During the early and intermediate stages of the pandemic, when quarantines and social isolation have been proposed, did you continue taking your baby/child to the follow-up preventive appointments in the Children Preventive dental program? () Yes () No () Only for emergency dental care |

|||||||

| 10.1. If your answer was no to the previous question, what was the reason for not taking your baby/child to routine appointments? () I didn't want to take the risk of contaminating myself and my family () Medical and dental appointments were not urgent, and could wait for a more suitable date () A member of my family tested positive for Covid-19 and we were not allowed to go out. () Other |

|||||||

| 11. Were you afraid of going out with your baby/child during quarantine and social isolation and becoming infected? () Yes, too much () Yes, a little () No |

|||||||

| Impact of the pandemic on oral health care | 12. Did you have doubts about how to maintain baby/child’s oral health guidelines during quarantine? () Yes () No |

||||||

| 13. Did you have doubts about what to do in case of eruption or early eruption of your baby/child's teeth during quarantine or social isolation? () Yes () No |

|||||||

| 14. Did your baby/child have any type of dental trauma during quarantine and social isolation? () No () Yes, but we did not seek dental care () Yes and we sought emergency dental care |

|||||||

| 15. Did your baby/child had toothache during the quarantine period and social isolation? () No () Yes, but we did not seek dental care () Yes and we sought emergency dental care |

|||||||

| 16. Was there a reduction in your baby/child's oral hygiene habits during the pandemic? () Yes () No |

|||||||

| 16.1. If your answer was Yes to the previous question, what was the reason for changing your baby/child's oral hygiene habits? () My family and I were stressed and ended up neglecting our baby/child’s oral hygiene () We didn't know how to proceed with our baby/child's oral hygiene and ended up not doing it () We were busy and didn't have time () Other |

|||||||

| Impact of the pandemic on eating habits | 17. Did your baby/child's eating habits changed during the pandemic? () Yes () No |

||||||

| 17.1 If your answer was Yes to the previous question, what was the reason for these eating habits changes? () My family and I were stressed and ended up eating more or more sugar-rich foods () We were eating cheaper food to save money and then our meals end up being less healthy () My family and I were eating healthier foods than before () I allowed my baby/child to eat whatever he/she wants because I was out of patience and overwhelmed |

|||||||

| Impact of the pandemic on the family income | 18. Did your family income changed with the pandemic? () No () Yes, my family income was reduced by about 30% () Yes, my family income was reduced by about 50% () My family and I totally lost our income |

||||||

| Change in Family Income | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other questions | No | Yes, a Slight Reduction | Yes, a Great Reduction | Total Loss of Income | p-value | |||

| - | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | - | - | ||

| Reduction in hygiene habits | - | - | - | - | X2=18.93 DF=3 <0.001* |

|||

| Yes | 19 (13.6%) | 30 (25.9%) | 23 (40.4%) | 0 (0%) | ||||

| No | 121 (86.4%) | 86 (74.1%) | 34 (59.6%) | 5 (100%) | ||||

| Change in eating habits | - | - | - | - | X2=2.03 DF=3 0.566 |

|||

| Yes | 29 (20.7%) | 25 (21.6%) | 9 (15.8%) | 2 (40%) | ||||

| No | 111 (79.3%) | 91 (78.4%) | 48 (84.2%) | 3 (60%) | ||||

DF=degree of freedom.

3. RESULTS

The response rate was 79.5% since 318 out of 400 questionnaires sent were answered. Most respondents were mothers/ females (90.3%), and 9.7% were fathers/ males, with a mean age of 33.47 years (SD ±7.23). Only 4.4% tested positive for COVID-19.

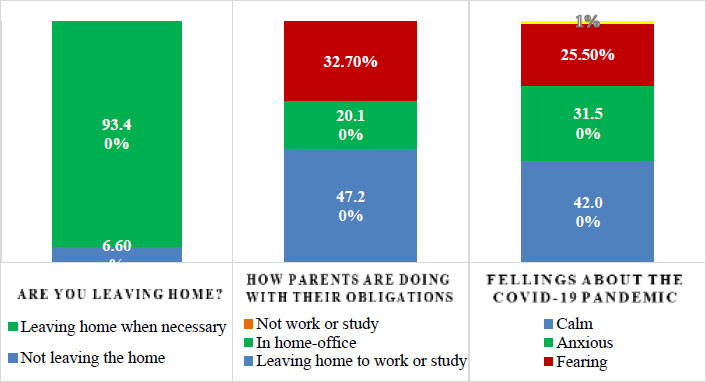

All parents were respecting the quarantine at the time when the survey was conducted. Besides that, they were going out only when necessary (93.4%) or not leaving home anyway (6.6%); 47.2% of the parents are leaving home to work or study, 20.1% are at home-office, and the other 32.7% do not work or study. Regarding their feelings about the COVID-19 pandemic, 42% reported being calm, 31.5% were anxious, 25.5% were fearing the pandemic, and 1% were indifferent (Fig. 1).

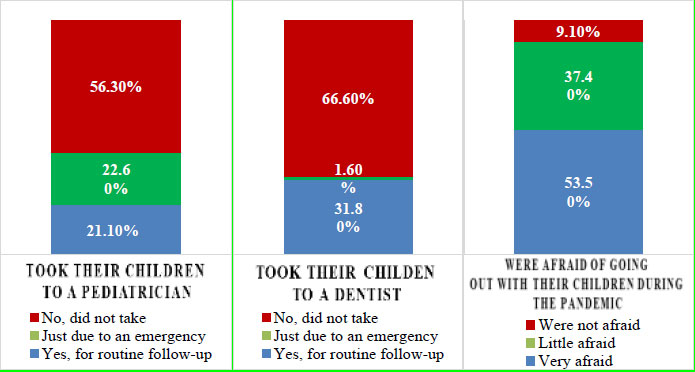

During the stay-at-home orders and quarantine, only 21.1% of the parents continued to take their child to the pediatrician for routine follow-up; 22.6% took the children to the doctor only due to an emergency, and 56.3% did not take children to the doctor (Fig. 2). The children's mean age was 2.72 years (SD ±1.39, ranging from 3 months to 6 years of age).

Regarding dental care, during the early stages of the pandemic, when quarantines were suggested, 31.8% of the parents sought dental care at baby clinics, and 1.6% sought dental care only due to an emergency with their children. The other 66.6% did not seek dental care at the Baby Clinics because it was closed or the staff canceled the scheduled appointments. Most parents (53.5%) reported being very afraid of going out with their babies/ children during the pandemic and getting infected, 37.4% were a little afraid, and 9.1% were not afraid (Fig. 2).

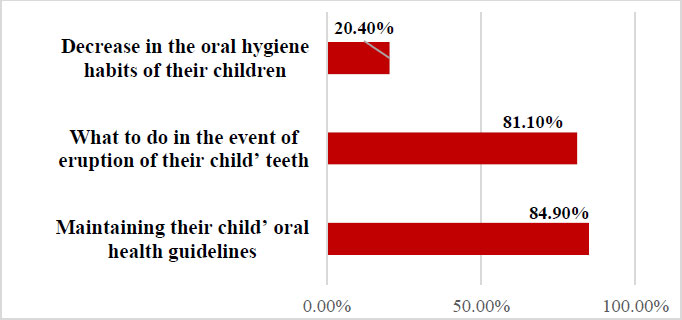

Most parents (84.9%) reported having doubts about maintaining their baby/ child’s oral health guidelines during quarantine, and 81.1% had doubts about what to do in the event of an eruption of their baby/ child’s teeth. Some parents (20.4%) reported a decrease in their babies/ children's oral hygiene habits during the pandemic (Fig. 3). When asked why, the parents' responses were varied, such as changes in the child’s behavior, lack of time, carelessness, changes in the daily routine, parents were overloaded, and the children's teeth were soft or bursting, causing pain.

Some parents (20.4%) also reported changes in their children's eating habits during the pandemic (Fig. 3). The reasons mentioned were that the family was more stressed and eating more or more sugar-rich foods during the pandemic, and parents were out of patience. They overwhelmed and let children eat whatever they wanted, and also that the family was eating healthier than before.

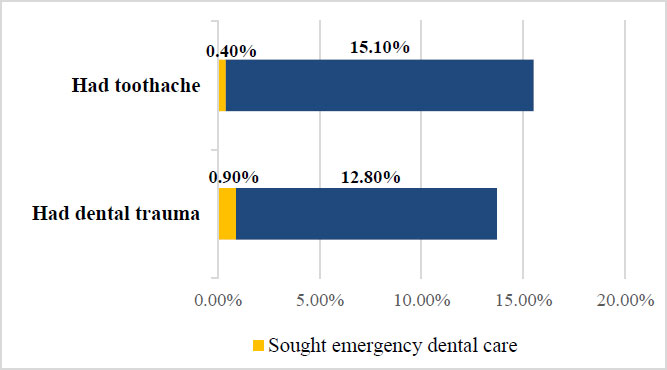

A few parents (12.8%) reported that their children had dental trauma during the pandemic, but only 0.9% sought emergency dental care. Also, 15.1% of the parents reported that their babies/ children had toothache during the pandemic, but only 0.4% sought emergency care. Some parents also reported that their babies/ children's toothache was due to the physiologic teeth eruption (Fig. 4).

Most families (54.4%) disclosed a reduction in the family income with the COVID-19 pandemic, with 36.5% reporting a slight reduction and 17.9% drastic reduction; 1.6% had completely lost the family income. There was a significant association between family income and hygiene habits, indicating that the parents with reduced income reported a significantly greater reduction in oral hygiene habits (Table 2).

4. DISCUSSION

This survey was carried out in Arapongas, a medium-sized city in the north of Paraná, Brazil. Arapongas have 124,810 inhabitants, and the estimated 0-6 years of the population is approximately 10,100 children. The average monthly wage for formal workers is approximately $456 [10]. This information is important because Paraná is one of the richest states in Brazil, and, at the time the survey was conducted, despite the high number of deaths, it was not considered one of the most affected cities by COVID-19 in Brazil [11].

With the COVID-19 pandemic, the world faced changes and challenges in general. There were changes in family habits and routines of the entire world population. Some groups of people were more affected than others. It has become difficult for parents with babies and children to balance the home office, household chores, and childcare. For this reason, parents often feel overwhelmed. Besides, some parents had lost their jobs had their income reduced, and feelings of insecurity, concern and fears frequently led to a reduction in the quality of life of many families worldwide [12]. During the pandemic, most parents who responded to this survey reported a reduction in family income [9] (Table 2), from a slight reduction to a complete loss of income. This certainly increases fears, anxiety, stress, and instability [12-15]. According to Almeida et al. [16], 55% of the Brazilian families reported decreased family income and 7% were left without any income. In addition to that, it must have been taken into account that the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the inequality and socioeconomic deprivation that affected developing countries to a greater extent than before [17]. Kalash [18] stated that the fallout from COVID-19 would reveal the depth and range of social, economic and political disparities faced by families in richer countries like the USA. This was especially difficult in Brazil, which demonstrated considerable inequality among regions and ethnic groups [17]. It is known that people who live in poverty might not be able to follow the requested recommendations for prevention, like hand hygiene and social distance [19, 20]. However, it is important to highlight that this research was conducted in Paraná, which is one of the states with the best economic indicators in Brazil [17].

For the children, there was the suspension of regular classroom classes and other activities outside the home, adaptation to online classes, and social distancing from friends, among other aspects. This changed the children’s normal routine, making them more anxious and stressed. Besides the fear of unknown illnesses and what may happen in the future, the stress and anxiety of their parents the children generate even more tension in babies and kids, regardless of age [21].

The suspension of school programs and sports activities made children spend longer periods at home, adding to the stress of a new routine and anxiety inherent in the pandemic, leading to an increase in food consumption, including ultra-processed and calorie-dense foods [22-24]. In the present study, only 20.4% reported changes in the eating habits of their children during the pandemic, and the reasons mentioned were that the family were more stressed and eating more or consuming more sugar-rich foods and that parents were out of patience and overwhelmed and let children eat whatever they want.

Besides, 22.6% of the parents reported a decrease in the oral hygiene habits of their babies/ children during the pandemic (Fig. 3). It could be speculated that this is due to changes in the child’s behavior, lack of time, carelessness, changes in the daily routine, parents being overloaded, and the children’s teeth being soft or bursting, causing pain. This is in accordance with Baptista et al. [25]. In their study, 22.9% of parents reported that their child’s oral hygiene was poor during social distancing. They also found that the change in the children's routine led to sleep disturbances associated with poor oral hygiene.

The minority of the parents sought dental care at the baby clinics during the pandemic due to the fear of contamination by the coronavirus (Fig. 2). It can be speculated that this fear of contamination happens even though children most often have mild forms of the disease, but still, they are considered as possible SARS-CoV-2 carriers [26, 27]. Similar results were found by Sun et al. [28], who reported that a considerable percentage of parents would not take their children to the dental department even if they had severe dental pain and thought that the dental environment could be more dangerous than other environments. Chisini et al. [8] also reported a great reduction in pediatric dental treatments in the Brazilian Public Health System.

This decrease in dental care and hygiene habits, even if by the minority of the interviewed parents, added to the changes in dietary habits, including more foods rich in sugar [9], may generate major oral health problems in these children/ babies in the future. This is a concern that can be prevented now with information to parents and families. In this sense, the use of “Tele-Dentistry” [29], as well as some remote assistance to these parents with babies and young children, should be used, and it will certainly prevent the increased incidence of caries and other oral health problems in these children in the future.

We all know that the pandemic has challenged health professions and also Dentistry. Concerns regarding the dentists, dental staff and patient’s safety and the lockdowns and quarantines determined in many countries caused the cessation or reduction of routine dental care [13, 30-32], compromising preventive appointments. Most parents reported having doubts about maintaining their baby/ child's oral health guidelines during quarantine and doubts about what to do when their babies' teeth erupt. This information and doubts can be solved with a remote consultation, phone call, text messages, video conferencing, or distance care. The “Tele-Dentistry” was approved in Brazil on June 4th, 2020, by the Federal Council of Dentistry [33], and allows parents and children to have video or phone appointments, with dentists providing a safe triage and sharing information on oral hygiene and health [29]. These parents and babies/ children need attention, and this could not be neglected during the pandemic. Moreover, despite precautions that must be taken during the pandemic, the maintenance of children's oral care is essential, especially considering the occurrence of dental pain and its negative impact on the children's oral health-related quality of life [8]. Besides that, dental teams must ensure they remain current in their understanding of local, regional and national guidance in a climate of uncertainty and frequent change to optimize safety for dental care providers and patients [26].

One limitation of the present study is the sample's restricted character, which belonged to a limited region of a single Brazilian state. Further research with a bigger sample size and not so restricted geographically and economically is needed. Besides that, associations with parents' emotional reactions could be performed related to the changes in hygiene habits and job situations. Besides that, this survey was carried out in the early/ intermediate stages of the pandemic in Brazil, influencing the parents' opinions. We recommend conducting the same study in the current state of the pandemic to compare the results.

CONCLUSION

Within the limits of this questionnaire-based study, performed during the early and intermediate stages of the pandemic, when stay-at-home orders were suggested, the conclusions of this study were:

- The parents of children aged 0-6 were afraid to take their children to medical and dental appointments, impacting the dental care of babies and children.

- Only 21.1% of the parents continued to take their children to the pediatrician for routine follow-up.

- 53.5% of the parents were afraid of going out with their babies/ children during the pandemic and getting infected.

- The parents also claimed that their family routines of food and oral hygiene were altered.

- There parents with reduced income during the pandemic reported a significantly greater reduction in oral hygiene habits.

ABBREVIATIONS

| COVID-19 | = Coronavirus Disease |

| WHO | = World Health Organization |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study was approved by the Ingá University Center Uningá Research Ethics Committee (CAEE 35713220.6. 0000.5220).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals were used in this research. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committees and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

The parents would agree with their participation after signing the informed consent term.