All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Dental Amalgam from the Past to the Present: Utilization among Ministry of Health Dental Clinics in the Makkah Region of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Abstract

Background:

Amalgam fillings were invented and introduced to dentistry in France and England during the 1800s. It has since become one of the most reliable dental filling materials to treat dental caries. Dental amalgam contains approximately 50% elemental mercury, a source of occupational exposure among dental personnel and non-occupational exposure among patients.

Objective:

This study describes the use of dental amalgam in Makkah region dental clinics as a direct restorative material compared to composite and glass ionomer cement.

Methods:

This longitudinal retrospective study included 335 dental clinics in Makkah and Jeddah, the two largest cities in the Makkah region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Annual statistical data were obtained from the Directorate of Dentistry, Makkah and Jeddah Health Affairs, Ministry of Health. Data related to the restorative materials used (composite, glass ionomer cement (GIC), and amalgam) were counted for 11 years starting from 2009 to 2019 for Makkah city, and the restorative materials used (composite, GIC, and amalgam) from 2018 to the first quarter of 2021 for Jeddah city.

Results:

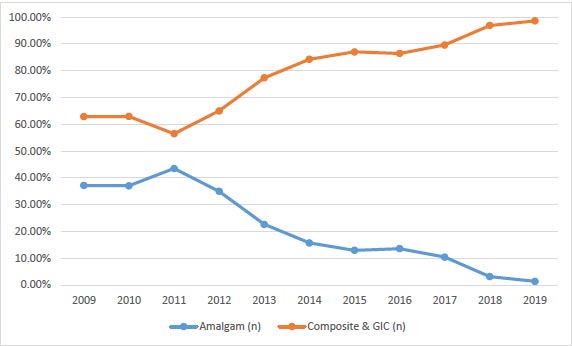

There was a slight increase in the number of amalgam restorations in Makkah from 2009 (37.15%) to 2011 (43.52%), followed by a gradual decrease until 2019 (1.39%). In Jeddah, there was a slight increase in amalgam restorations from 2018 (9.39%) to 2019 (11.03%). However, the use of amalgam restorations reduced sharply in 2020 (3.27%) and in the first quarter of 2021 (3.53%).

Conclusion:

There is a recognizable decreased trend in amalgam utilization in the Makkah region. Amalgam use is being phased down despite the lack of official regulation on its use.

1. INTRODUCTION

Amalgam fillings were invented and introduced to dentistry in France and England during the 1800s [1]. Amalgam has become one of the most reliable dental filling materials to treat dental caries [2]. Powdered silver, tin, and copper are combined with metallic mercury (liquid mercury, quicksilver) to produce the dental amalgam within the dental clinic. It is estimated that more than one billion dental amalgam fillings were placed between 1988 and 2008 in the United States alone [3].

Mercury (Hg) is a known toxic substance found in nature. Many people may have been exposed to elemental mercury (Hg0), inorganic mercury (Hg2+), and organic methylmercury (MeHg). Dental amalgam contains approximately 50% elemental mercury. Mercury from dental amalgam can be released into the environment in various ways, such as from improper dental waste management practices and crematoria. Elemental mercury from dental amalgam and other sources of inorganic mercury contaminate air, land, and groundwater and can be biomagnified throughout the food chain as methylmercury [4]. The transformation of inorganic mercury pollution into methylmercury has been proven scientifically [5].

Studies have examined the neurological outcomes likely to be caused by mercury toxicity, such as Minamata disease, which resulted from environmental pollution by inorganic mercury and its subsequent transformation to methylmercury through the food chain [6-10]. Methylmercury is a potent neurotoxin that can cause physiological, neurological, behavioral, and reproductive harm to fish and wildlife [11].

During the twentieth century, the health hazards of mercury in dental amalgam were debated. In 1989, Clarkson claimed that occupational exposure to dental amalgam among dental personnel and non-occupational exposure among patients was a serious threat because it may lead to neurological disorders (e.g., erethism) [12]. Debate increased during the 1990s for three key reasons. First, many publications demonstrated the adverse effects of dental amalgam on the human body’s physiological processes. Second, public awareness of potential mercuric poisoning increased. Finally, advances in analytical chemistry led to the effective detection of systemic mercury at very low levels [4, 5]. However, the hazardous effects of dental amalgam restorations on human health were based on risk estimation rather than true causality [13].

The Minamata Convention on Mercury, or “Minamata Convention” (named after Minamata, Japan—the location of the worst-ever case of mercury pollution), was signed in October 2013 [14]. Its goal is to protect human health and the environment from mercury and mercury compounds throughout mercury’s life cycle, including the “phasedown of dental amalgam use.” This agreement entered into force on 16 August 2017. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia joined the Minamata Convention in February 2019, and the Saudi Food and Drug Authority (SFDA) announced its plan would take effect in January 2020 [15].

This study examined amalgam utilization among dentists in the Ministry of Health (MOH) in the Makkah region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, since 2009. The findings of this study could serve as the foundation for future comparisons.

| City | Type | Name of theDental Clinic | Number of Dental Clinics | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Makkah | Specialized DentalCenters | Alnoor | 28 | 133 |

| King Abdulaziz | 18 | |||

| King Faisal | 10 | |||

| Primary HealthcareCenters | Aljamum Health Sector | 12 | ||

| Khulais Health Sector | 11 | |||

| Alkamel Health Sector | 10 | |||

| Makkah Praimary HealthCare Centers | 37 | |||

| Hospitals | Khulais | 2 | ||

| Hera | 4 | |||

| Alkamel | 1 | |||

| King abdulaziz hospital | 3 | |||

| Public health | Primary healthcarecenters | 84 | ||

| Jeddah | Specialized DentalCenters | King Fahad Hospital | 43 | 202 |

| Althaghr Hospital | 8 | |||

| Specialized Dentalcenter | 40 | |||

| PrimaryHealthcare Centers | King Fahad Sector | 23 | ||

| Althaghr Sector | 8 | |||

| King Abdullah Sector | 12 | |||

| East Jeddah Sector | 14 | |||

| King Abdulaziz Sector | 11 | |||

| Adham Sector | 4 | |||

| Al-llith Sector | 10 | |||

| Rabegh Sector | 9 | |||

| Hospitals | East Jeddah Hospital | 5 | ||

| King Abdullah | 4 | |||

| King Abdulaziz | 3 | |||

| Adham | 2 | |||

| Al-llith | 2 | |||

| Rabegh | 4 | |||

| Total | 335 | |||

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

This longitudinal retrospective study focused on the Makkah region in the western area of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, which contains 335 dental clinics in two large cities: Makkah and Jeddah. Of the 335 dental clinics, 133 were in Makkah, and 202 were in Jeddah (Table 1). The study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board – Jeddah, MOH (approval number: A01148). Annual statistical data for the two cities were mostly obtained from the Directorate of Dentistry, Makkah and Jeddah Health Affairs, while others were collected directly from the clinics. Data related to the restorative materials used (composite, glass ionomer cement (GIC), and amalgam) were collected for 11 years starting from 2009 to 2019 for Makkah city, and the restorative materials used (composite, GIC, and amalgam) from 2018 to the first quarter of 2021 for Jeddah city. There were incomplete records for Makkah from 2020 to 2021 and Jeddah from 2009 to 2017. This missing data was not available in their records and could not be obtained by any means. The data were summarized and used for descriptive trending comparisons.

3. RESULTS

The total records were 25,343, in which the type of permanent restorations applied in Makkah from 2009 to 2019 and in Jeddah from 2018 to the first quarter of 2021 analyzed. Furthermore, data on permanent restorations in Makkah and Jeddah in 2018 and 2019 were compared.

3.1. Makkah

Restoration records for Makkah showed 268,651 restorations were applied in dental clinics in all primary healthcare centers and hospitals between 2009 and 2019. Amalgam was used in 56,690 (21.10%) restorations, and composite and GIC were used in 211,961 restorations (78.90%) (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Fig. (1) shows a slight increase from 2009 to 2011 in the use of amalgam restorations, followed by a gradual decrease in the utilization rate from 2011 to 2019.

| Year | Amalgam | Composite & GIC | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | N | |

| 2009 | 9,347 | 37.15% | 15,813 | 62.85% | 25,160 |

| 2010 | 8,492 | 37.05% | 14,426 | 62.95% | 22,918 |

| 2011 | 9,526 | 43.52% | 12,364 | 56.48% | 21,890 |

| 2012 | 10,789 | 35.00% | 20,036 | 65.00% | 30,825 |

| 2013 | 7,083 | 22.63% | 24,216 | 77.37% | 31,299 |

| 2014 | 2,868 | 15.71% | 15,384 | 84.29% | 18,252 |

| 2015 | 2,340 | 12.95% | 15,731 | 87.05% | 18,071 |

| 2016 | 2,774 | 13.55% | 17,701 | 86.45% | 20,475 |

| 2017 | 2,205 | 10.40% | 19,006 | 89.60% | 21,211 |

| 2018 | 817 | 3.11% | 25,412 | 96.89% | 26,229 |

| 2019 | 449 | 1.39% | 31,872 | 98.61% | 32,321 |

| Total | 56,690 | 21.10% | 211,961 | 78.90% | 268,651 |

| Year | Amalgam | Composite% | GIC% | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | N | |

| 2018 | 1,837 | 9.39% | 12,561 | 64.18% | 5,172 | 26.43% | 19,570 |

| 2019 | 2,554 | 11.03% | 15,256 | 65.90% | 5,340 | 23.07% | 23,150 |

| 2020 | 311 | 3.27% | 5,925 | 62.25% | 3,282 | 34.48% | 9,518 |

| 2021 | 236 | 3.53% | 4,183 | 62.64% | 2,259 | 33.83% | 6,678 |

| Total | 4,938 | 8.38% | 37,925 | 64.37% | 16,053 | 27.25% | 58,916 |

3.2. Jeddah

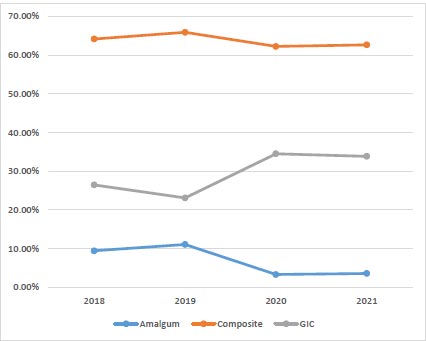

Permeant restoration records for Jeddah were only available from 2018 to the first quarter of 2021. During this period, 58,916 restorations were applied in 12 dental clinics and hospitals (no data were available for primary health care centers). Among the 58,196 restorations, 4,938 (8.38%) were amalgam restorations, 37,925 (64.37%) were composite restorations, and 16,053 (27.25%) were GIC restorations (Table 3).

As shown in Fig. (2), there was a slight increase in the utilization of amalgam from 2018 (9.39%) to 2019 (11.03%). However, the percentage reduced sharply in 2020 (3.27%) and in the first quarter of 2021 (3.53%). Regarding composite restorations, the utilization rate did not vary dramatically in 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2021 respectively. Conversely, GIC had similar utilization rates in 2018 (26.43%) and 2019 (23.07%), but the rate increased in 2020 (34.48%) and the first quarter of 2021 (33.83%).

3.3. Utilization Rate between Makkah and Jeddah (2018–2019)

Data were available to compare the permanent restoration utilization rates in Makkah and Jeddah (Table 4). Amalgam use was lower in Makkah and reduced over time (3.11% in 2018 versus 1.39% in 2019), while Jeddah showed a high and increased usage of amalgam restorations over time (9.39% in 2018 versus 11.03% in 2019).

| Year | Amalgam | Composite & GIC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Makkah | Jeddah | Makkah | Jeddah | |

| 2018 | 817 (3.11%) | 1,837 (9.39%) | 25,412 (96.89%) | 25,412 (90.61%) |

| 2019 | 449 (1.39%) | 2,554 (11.03%) | 31,872 (98.61%) | 31,872 (88.97%) |

4. DISCUSSION

This study described the utilization rate of amalgam according to available data in two cities in the Makkah region (Makkah and Jeddah) in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The results showed a decrease in amalgam restoration in the Makkah region over the years.

The introduction of the Minamata Convention sought to implement a “phasedown of dental amalgam use.” However, even before the declaration of the agreement, the Swedish national parliament decided against supporting amalgam fillings via national dental insurance in 1999, significantly affecting the consumption of dental amalgam. In 2009, the Swedish government banned the import and use of dental amalgam, among other mercury-containing products. In 2011, Norway banned mercury-containing products and declared an amalgam-free dental practice [16].

Amalgam utilization rates in Makkah (1.93%) in 2019 and Jeddah (3.53%) in the first quarter of 2021 were surprisingly low. Even before the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia joined the Minamata Convention in 2019, the rate of amalgam use in Makkah was 10.40% in 2017, slightly higher than New Zealand (7.1%) [17]. However, a significant decrease in amalgam use was observed in Makkah (3.11%) in 2018 to levels lower than New Zealand’s for the previous year. The use of amalgam in New Zealand decreased from 52.3% in 1998 to 7.1% in 2017. Considering the early acceptance of the Minamata Convention by New Zealand in October 2013 [14], the current study’s results showed a rapid reduction in amalgam utilization within a few years [17]. On the other hand, Finland reported a total rate reduction of up to 3% in 2016 [15].

Multiple countries that have phased down the use of dental amalgam have shown significant early reductions; for example, Denmark reported only 5% of restorations used amalgam in 2013. Further, the Netherlands used amalgam in less than 1% of restorations in 2011 [15]. The utilization rates in the Netherlands were remarkably low compared to the results in the current study for the same year. Further, Hungary (12%) and Singapore (16%) revealed higher rates of amalgam restoration in 2012 than the previously mentioned countries [15] but lower than Makkah, which showed a 35% utilization rate in 2012.

5. LIMITATIONS

Though the collected data was enough to prescribe the trend of dental amalgam restoration utilization rates, the incomplete data records were unfortunate.

CONCLUSION

The findings from this study indicate a recognizable improvement in dental service providers’ awareness of amalgam restoration with decreased utilization rates. Amalgam use has being phased down despite the lack of official regulation. Further studies are needed to examine amalgam utilization in other regions in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| GIC | = Glass Ionomer Cement |

| SOM | = Soil Organic Matter |

ETHICAL STATEMENT

The study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board–Jeddah, MOH (approval number: A01148).

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The summarized data are available upon request from the principal author. As mentioned in the Methods section, the data can be obtained from its source, which is the Directorate of Dentistry, Health Affairs, Saudi Arabia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.