All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Analysing the Social Responsibility among Dentists of Ethiopia: A Cross-sectional Study

Abstract

Objective:

Dentistry is essentially a business at present. The present study aimed to analyze the meaning and implications of social responsibility among the dentists of Ethiopia. It further evaluated whether the dental professionals of Ethiopia consider themselves as responsible for equitable distribution of dental care.

Materials and Methods:

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 200 dentists practicing in Addis Ababa and Jimma city of Ethiopia in the academic year 2017-18. Simple random sampling technique was used to collect the required sample. The results were recorded by filling the predesigned self-administered questionnaire by the dentists. The descriptive statistics and cross-tabulation were used for data analysis using the software SPSS version 20.

Results:

Among 200 dentists, 168 dentists (which make up 84% of the sample of 200 dentists) considered finance as a major barrier to accessing dental health care in Ethiopia. Further, 168 (84% of the sample) said that the meaning of social responsibility in the dental profession was providing better access to dental care to those who are underserved. All of the participants (100%) who lived in Addis Ababa and 92% of participants of Jimma thought that social responsibility should be taught as a part of public health dentistry.

Conclusion:

Dentists were aware of their responsibilities in terms of providing better access to dental care to those who are underserved, but most of them considered finance as the major barrier. So, they looked at dentistry primarily as a business. This shows not only dentists working in the dental profession are socially liable for guaranteeing fair admittance to dental care, but the society and government are also responsible for its proper implementation.

1. INTRODUCTION

Ethiopia is the second most populous sub-Saharan African country, which has a population of 105 million with 2.5% annual growth rate [1]. 80% of its total population lives in rural areas. To have access to health care using available resources, the active participation of the community is a mandatory requirement. Also, it is essential to understand the psychosocial, cultural, and environmental factors associated with the community before developing strategies for their health care. It is the responsibility of all the dental practitioners of the region to take positive steps towards the improvement of the community’s dental health through dental treatment, dental education, strategies, and increased access to quality oral healthcare [2]. They are also responsible for sound public health and primary preventive measures for all people, including the poor, underprivileged and underserved [2]. Some dentists of the present society consider dental practice in terms of financial benefits only. They take it as a business so they are practicing it as a market providing service. They would treat only those who are able to afford their expensive dental treatment. Even the dentists practicing in developed countries seem to have the same attitude and practices. However, disagreement has been observed related to this matter among certain other dentists who see themselves as socially accountable for the oral health of the underprivileged in order to ensure fair access to dental treatment. So, the question arises is ‘whether the individual dentist working for the dental profession, or society as a whole, is responsible for the dental care of the individuals [3]?

Fifteen years ago, a research was conducted to trace “Are we creating socially responsible dental professionals in our society?” This is equally important these days as there are several issues that create barriers to proper dental care. These factors include poverty, cultural sensitivity, and the practice of dentistry for financial benefits only [4]. The concept of social responsibility has been considered in education, moral development, civic engagement, community service, sustainable development and within the corporate sector and business ethics. We should think about ‘social responsibility in dentistry’ as we do not know a clear explanation regarding the concept or its application by dentists. Nobody can deny the fact that a few dentists attend to the needs of elders during residential care struggle to balance financial cost with the accessibility of care. On the contrary, little is known about the struggle the dentists face while addressing their social responsibilities toward providing dental health care to those who are underserved.

To the best of my knowledge, no research on social obligations among dentists has been undertaken in Ethiopia. This study was carried out to investigate the social responsibilities of Ethiopian dentists and also to investigate the fact that who is accountable for the equal distribution of dental health care: the dental profession, society, or the government.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted during the year 2017-18 after obtaining of the approval of the study protocol from the Ethical Clearance Committee of the Institution. This was a cross-sectional survey among dentists of Addis Ababa and Jimma, conducted by two trained and calibrated investigators from the Department of Dentistry. A pilot study was carried out on 20 dentists in Addis Ababa to check the feasibility of implementing the study.

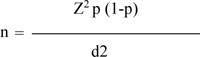

The below given formula was used for calculation:

|

n = sample size,

Z = level of confidence (95%) = 1.96,

p = expected prevalence (80%)

d = precision (5%=0.05)

By the above given formula, the sample size calculated was 246.

The sample was collected utilizing a simple random sampling procedure. The study comprised dentists who had provided their consent for participation and had thoroughly filled out the proforma. 46 dentists were eliminated from the research because some had not provided permission and others had submitted an incompletely filled out proforma. The survey comprised 200 dentists in all. In order to avoid any difficulty and to assure full cooperation in the study, informed written consent was acquired from the dentists who participated in the study prior to their involvement. It was stressed that the study was only for scientific purposes. Data were collected by having dentists fill out a pre-designed self-administered, closed-ended questionnaire proforma.

The questionnaire comprised two questions on socio-demographic characteristics and 10 questions on the line of Dharamsi (2007) [5] suitable for the existing situation. To avoid unforeseen time delays, the survey was pre-scheduled for the 2017-18 academic year. The questionnaire was written in English, Amharic and Oromia language. The software SPSS version 20 was used to analyse the data. The data were analysed using descriptive statistics and cross-tabulation.

3. RESULTS

Out of 200 respondents, 100 (50%) were from Addis Ababa and the rest 100(50%) were from Jimma. The majority of them were residing in the urban area (Table 1). Out of all the respondents, the great majority, 136(68%), had dental 1st degree and the rest 64 (32%), had 2nd degree. About 46% of respondents had 0-5 years of dental experience (Table 1). The majority of the respondents, 176 (88%), had a habit of reading dental literature to keep them self-updated regularly; on the other hand, 24 (12%) said that they update themselves sometimes. The majority of the respondents, i.e., 96 (48%), attended dental conferences regularly, while 64(32%) did not attend conferences at all. The rest, 24 (12%), attended if the conference was held at their workplace only; however, 16(8%) of the respondents did not attend regularly. About 84% of the dentists believed that finance was the major barrier in dental health care (Table 1). Among all, 164 (82%) of respondents believed that dental graduates should provide dental services to the needy, like filling and dentures. About 56% of dentists had studied public health dentistry separately during their graduation (Table 1). Out of 200 respondents, the majority, 156 (78%), said that both the government and private dental institutions should provide care to underprivileged, while 28 (14%) and 8 (4%) said only the government or only private dental institution should provide dental care to underprivileged population respectively. The rest 8 (4%) were unaware of this issue. Most of the respondents, 136 (68%), had participated in public dental health programs, while the rest, 64(32%), had never participated in any public dental health program. All the respondents believed that public dental health programs (school dental health programs, community dental health programs) are beneficial for the community. All of the respondents of Jimma, i.e., 100 (100%), and 88 (88%) of the respondents of Addis Ababa, stated that the meaning of social responsibility is to provide better access to dental care to those who are underserved. A total of 84% of dentists said that meaning of social responsibility for dentists is to provide dental care to the underserved (Table 1). About 131(80%) urban participants, 100% peri-urban, and 100% rural respondents had the same opinions. All the participants being 2nd degree holders, 79.4% of the 1st degree holders and all of the respondents whose work experience was greater than 6 years revealed that the meaning of social responsibility is providing better access to dental care for those who are underserved. All of the participants (100%) who lived in Addis Ababa and 92% of participants who lived in Jimma thought that social responsibility should be taught as a part of public health dentistry (Table 1) and 95% of urban, 100% of peri-urban and rural population thought that social responsibility should be taught as a part of public health dentistry. About 94% of participants having 1st degree, 100% of those with 2nd degree, and all the respondents who had professional practical experience for quite some years had a view that social responsibility should be taught as a part of public health dentistry.

| Location of Dental Practice | % of Dentists |

|---|---|

| Urban | 81.5 |

| Peri-urban | 16.5 |

| Rural | 2 |

| Years of Dental Practice | % of Dentists |

| 0-5 Years | 46 |

| 6-10 Years | 26 |

| 11-15 Years | 4 |

| 16-20 Years | 2 |

| >20 Years | 22 |

| Finance is the major barrier in Dental Health Care | % of Dentists |

| Yes | 84 |

| No | 16 |

| Taught Public Health Dentistry separately | % of Dentists |

| Yes | 56 |

| No | 44 |

| Meaning of Social Responsibility for Dentists | % of Dentists |

| Providing dental care to underserved | 84 |

| Denying to accept patients on Government plan | 2 |

| I don’t know | 14 |

| Social Responsibility should be taught in Public Health Dentistry | % of Dentists |

| Addis Ababa | 100 |

| Jimma | 92 |

4. DISCUSSION

The AGD (Academy of General Dentistry) of the United States observes that removing a few critical barriers will allow the American population to get access to and use accessible oral health services. Oral health literacy, psychological variables (converting literacy into healthy behaviours), financial reasons (economics of sustainable care delivery and unequal distribution) and patients with particular needs are some factors among the primary impediments which can be taken care to to better access to dental care [6].

The purpose of this study was to investigate the sense of responsibility among dentists who are directly involved in clinical practice towards their patients. The study revealed that 81.5% of dentists were practicing in urban area, 16.5% in peri-urban area, and only 2% practiced in the rural area. Since most of the population (about 80%) lives in rural areas, it shows unequal distribution of the availability of dentists; thus, there is an urgent need for interventions aimed at provision of dental service in peri-urban and rural areas. Approximately 84% of participants indicated financial difficulties as a key obstacle to receiving oral health care in Ethiopia. This finding is consistent with the findings in other industrialised nations, as well as literature. However, this is more significant than the findings of the research carried out by Bhaskar DJ. et al. (2014) [7] and similar to the finding of Vaibhav V. et al. (2012) [8].

The solutions for making dental treatment more affordable for poor communities are as follows: The timeframe for dental school students' loan repayments needs to be extended, with no tax obligation for the amount given in any year; tax breaks can be provided to dentists who open and run dental businesses assisting disadvantaged people. Scholarships should be offered to dentistry students in exchange for agreements to help underprivileged communities. Senior dental students should be encouraged to provide care in outreach community dental facilities under the supervision of dental faculty as part of their education [9]. Funds for regulatory support for expanded debt repayment schemes (LRPs) for dentistry school graduates should be increased. Government loan guarantees and/or subsidies to develop and equip dental clinics in poor and disadvantaged or financially challenged communities should be provided; funding for the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) loan repayment schemes for dental school graduates, as well as the National Health Service Corps and other public programs, should be increased, which would allow for the creation of more dentist positions for programs that support disadvantaged populations. Dental clinics within hospitals to address dental problems that are too complex or systemically affected to be treated in community clinics should be established; funding to dentists should be provided who work in hospital dental clinics to provide oral health care. According to the literature, the following procedures can be implemented to encourage efficient compliance with government-funded dental care programs and to assist poor people in achieving optimal oral health outcomes: a) raising Medicaid fees to at least the 75th percentile of dentists' real fees; b) eliminating needless paperwork with e-filing and simplified medical laws leading to quick reimbursement; c) educating medical officials about dentistry and offering funding for oral health programs; d) making dental examinations mandatory for children entering school, as well as teaching patients about the importance of proper oral hygiene in a culturally sensitive manner; e) increasing general dentists' understanding of the benefits of treating indigent populations; and f) encouraging funding from organisations that serve the poor. For example- W.K. Kellogg Foundation, Pew Charitable Trusts, Denta Quest, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation are financing organisations in the United States that promote the solutions stated above. Solutions for bridging the location gap, i.e., unequal distribution of dental professionals, include actively recruiting dental school applicants from underserved areas, establishing alternative oral health care delivery service units, including arrangements for transportation to and from care centres, and soliciting volunteer participation from the private sector, and encouraging private organisations, such as Donated Dental Services (DDS), fraternal organisations, and religious organisations to participate in these interventions. Also, there is a need to provide mobile and portable dental units to various age groups in underserved locations or places with impoverished people [6]. Among all, 88% of the dental graduates in this study reported reading dental literature to keep their knowledge updated. This was found to be more significant than the findings of Bhasker DJ. et al (2014) [7]. However, this result was in accordance with the finding of the study conducted by Vaibhav V et al. (2012) [8]. One of the reasons for this may be the availability of time and a less hectic schedule because they being freshly graduated dental professionals. Moreover, half of the participants attended the dentistry conference and 12% reported attending similar activities conducted near their job. One of the causes might be a desire to improve their expertise in their chosen sector. In contrast to the findings of Bhasker DJ. et al., most of them were aware of their social obligation to provide greater access to dental treatment to those who do not have the resources [3]. Approximately, 96% of participants believed that social responsibilities should be taught to DDM undergraduates as part of public health dentistry (community dentistry). The majority of participants (78%) agreed that both government and private dental institutions should provide oral health care to the underprivileged, whereas just 14% agreed that the government should provide oral health care to the underprivileged. Approximately, 82% agreed with the assertion that dental graduates should only serve poor patients in need of emergency care.

The majority of participants (about 68%) were engaged in dental health care programs and all participants believed that dentistry wellness programs provide benefits to the community. This clarifies that both the government and private institutions should facilitate community dental health programs and school dental health care programs in order to serve the society. All 2nd degree holders, 79.4% of 1st degree holders and all respondents with more than 6 years of work experience indicated that the definition of social responsibility is to give improved access to dental care to people who are underserved. This suggests that a dental professional's knowledge and experience improve their feeling of social responsibility. The study's strength is that it provides important information on social responsibility among Ethiopian dentists. The study's limitation is that the questionnaires used in this study were closed-ended, therefore, the information gained was curtailed. The study is externally credible since it follows a competent study design and the study's results are in line with its goals and objectives.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

We may infer that the involvement of general dentists, in collaboration with the dental team, is critical for enhancing access to and usage of oral health care services. Every member of society should acknowledge the significance of his/her own oral health and put that information into practice. Dental diseases are progressive and cumulative, becoming more complex with time. According to “Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General”, however, many of these common oral disorders are readily preventable. As a result, it is critical to understand if dentists are socially responsible or not. EDPA (Ethiopian Dental Professional Association), like AGD in the United States, should cooperate with other communities of interest to diagnose and resolve barriers to access and usage of treatment throughout the country. The study revealed that as dentist’s training and experience grow, they become more aware of their social obligation to underprivileged and needy individuals. They should work together to make sure that all Ethiopians receive the best comprehensive dental care, which will ultimately lead to optimal dental and overall health. During this process, they must focus on the patient and maintain awareness that dentistry works best as a preventive system. This emphasizes the significance of public health dentistry, especially in developing countries such as Ethiopia, as a major subject in dentistry because it teaches dentists social responsibility for the entire community, and both the government and private institutions should facilitate more and more community dental health initiatives and school dental health programs for serving those people in society who are underprivileged as an essential part of public health dentistry. Further studies are required to determine the influence of social responsibilities on various aspects of dentistry.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

The above-mentioned cross-sectional survey was carried out in 2017-2018 after clearance of the study protocol by the Institution's Ethical Clearance Committee in 2017.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Authors gave their consent for publication.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

STROBE Guideline were followed.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data and supporting conclusions of the study are accessible upon reasonable request from the corresponding author [A.R].

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors state that they have no financial or other potential conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The researchers would like to express their gratitude to all the dental practitioners who participated in the research.