All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Effect of Chlorhexidine Varnish and Fluoride Varnish on White Spot Lesions in Orthodontic Patients- a Systematic Review

Abstract

Aim:

The aim of this study is to critically review the studies that studied the effect of Chlorhexidine varnish and fluoride varnish on White Spot Lesion (WSL) in patients undergoing orthodontic treatment.

Materials and Methods:

The electronic database PubMed, The Cochrane Library, Medline, Embase, Google Scholar, Web of Knowledge along with a complimentary manual search of all orthodontic journals till the first week of December 2019 was searched. English language study performed on humans, randomized or nonrandomized clinical trials, comparing the effect of fluoride and chlorhexidine varnish on WSL was included in the review. Quality assessment of included studies was performed.

Clinical Significance:

The need for an adjunct oral hygiene aid to reduce the incidence and prevalence of white spot lesions in orthodontic patients is necessary. The use of these varnishes will aid in the same and thus make the adverse effects of fixed orthodontic treatment negligible.

Review of Literature:

Enamel demineralization is a significant risk associated with orthodontic treatment when oral hygiene is poor. Prevention of demineralization during orthodontic treatment is one of the greatest challenges faced by clinicians despite modern advances in caries prevention. The development of White Spot Lesions (WSLs) is attributed to prolonged plaque accumulation around the brackets.

Results:

The search identified a total of 3 studies that were included in this review. One study had Low risk of bias and the remaining 2 studies had moderate overall risk. Results showed that there was a reduction in the incidence of white spot lesions in orthodontic patients after application of chlorhexidine and Fluoride varnish.

Conclusion:

Low level evidence is available to conclude that the use of chlorhexidine varnishes and fluoride varnishes reduces the prevalence of white spot lesions in patients undergoing fixed orthodontic treatment. Due to its limitations, the results of this systematic review should be handled with caution and further well-planned Randomized Clinical Trial (RCT) are needed to provide a discrete conclusion.

1. INTRODUCTION

Enamel demineralisation adjacent to orthodontic brackets is one of the significant clinical problems associated with fixed orthodontic treatment. The number of patients who are willing to undergo orthodontic treatment has increased to a greater extent in recent years [1-5]. Fixed orthodontic treatment may take up to 1.5 to 2 years or more for its completion, depending on the type of malocclusion. Long term treatment will result in the formation of white spot lesions and in some cases, might affect the temporomandibular joint of the patient [6, 7]. An index has been developed for determining the need, complexity and severity of malocclusion for Indian population [8]. The difference in the ethnic variations and genetic predisposition of malocclusion showed the need for various analyses pertaining to the particular population [9]. White spot lesions develop as a result of prolonged plaque accumulation on the affected surface, commonly due to inadequate oral hygiene [9, 10]. The attitude towards oral hygiene varied between different patients [11]. The most frequent iatrogenic problem in orthodontics is white Spot Lesions (WSLs). Constant presence of fluoride ions in the vicinity of the enamel around the bracket bases helps protect against the development of WSLs [12]. Orthodontic brackets and auxiliaries used for fixed orthodontic treatment favour accumulation of dental biofilm, increasing the prevalence of periodontopathogenic and cariogenic bacteria and the risk for the development of white spot lesions and gingivitis [13-15]. A study on the contamination of toothbrushes showed that storage of toothbrush will affect the oral microbiological profile [16]. Clinically, the demineralization sites are detected as opaque and porous White Spots Lesions (WSLs) that may compromise the final result of the orthodontic treatment. The development of these lesions mainly occurs due to difficulties with oral hygiene. The incidence of WSLs during orthodontic treatment may vary between 15% and 85% [17].

After bracket placement, WSLs can be identified within 1 month, although it takes at least 6 months before caries become notable [18]. These lesions are predominantly in sites adjacent to brackets and are usually formed at the buccal surfaces, especially in the gingival region [19, 20]. Plaque also harbors the cariogenic bacteria, potentially capable of hard tissue damage, especially at the bracket margins [21]. Chemical and mechanical cleansing of the tooth surface with regular brushing and mouth rinses can help to reduce the formation of plaque and its accumulation. Therefore, it prevents dental and gingival diseases during orthodontic appliance therapy [22]. The efficacy of oral rinses in orthodontic patients has been studied earlier [23]. Patients with mouth breathing are more prone to the formation of white spot lesions around the bracket surfaces [24]. Good plaque control is very difficult in patients with fixed orthodontic appliances. To improve mechanical plaque removal, incorporation of a chemotherapeutic agent such as an antibacterial mouth rinse into the oral hygiene regimen can be helpful [25].

Several methods have been suggested to improve the cariostatic effect of fluoride at low pH. Acid-resistant coatings of calcium fluoride or titanium fluoride on the enamel surface and the use of fluoride in combination with antimicrobials have been suggested [26]. It is well known that chlorhexidine inhibits acid production in plaque and thus reduces the pH fall during sucrose challenges [27]. In an in situ study with specially banded premolars to be extracted, it was demonstrated that daily mouth rinsing with chlorhexidine and fluoride was more efficient in the reduction of mineral loss than was rinsing with fluoride alone [28].

However, chlorhexidine mouth rinses have several adverse effects, including a bitter taste and discoloration of the teeth and the tongue [29]. For such a rinse to be effective during orthodontic treatment, patients would have to rinse twice daily for 1 to 2 years. To overcome these limitations, the development of mouth rinses using natural materials such as watermelon has been studied earlier [30, 31]. In that respect, one study found that compliance with even the less objectionable fluoride mouth rinsing was less than 15% [32]. Therefore, there is a need for preventive programs for orthodontic patients that are less dependent on patient compliance. Several researchers have reported an antimicrobial effect in plaque when a varnish containing chlorhexidine and thymol (Cervitec, 1% chlorhexidine, 1% thymol; Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein) is used [33-36]. The aim of this study is to review various studies that compare the effect of Chlorhexidine varnish with fluoride varnish on white spot lesions in patients undergoing orthodontic treatment.

2. STRUCTURED QUESTION

The question that needs to be addressed in this study is-

‘Does the use of chlorhexidine varnish prevent the incidence of white spot lesions as compared to the use of fluoride varnish in patients undergoing orthodontic treatment?’

3. MATERIALS AND METHODS

3.1. Registration and Protocol

This trial has been registered to PROSPERO (International prospective register of systematic reviews) and the registration number is CRD42019128488 in accordance with PRISMA checklist of systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

3.2. Source of Information and Selection of Studies

Two independent authors (A.G. and S.D.) screened the initial titles and abstracts to find all the eligible studies. The full texts were retrieved according to their inclusion and exclusion criteria. All differences of opinions were discussed and resolved.

3.3. Search Strategy

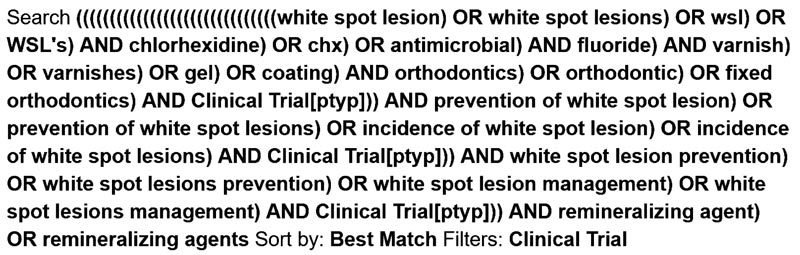

A systematic literature search was done to identify the articles that have described the effect of chlorhexidine and fluoride varnish on the incidence of white spot lesions in orthodontic patients. All the relevant articles were selected using PubMed, PubMed central and Cochrane database from April 1976 to the first week of December 2019. The search was performed using the keywords and terms mentioned in Fig. (1).

A complementary search was also done in other databases like the web of knowledge, google scholar, and a manual search was done in the following journals- World journal of orthodontics, American journal of orthodontics and Dentofacial orthopaedics, European journal of orthodontics, Journal of clinical orthodontics, Seminars in orthodontics and Angle orthodontics. Quality assessment of included studies was performed. The results were screened with title and abstract screening to select which studies will be included in this review. The references used in these studies were hand-searched to see if there were any clinical trials included. The date of the last search was done in December 2019.

3.4. Eligibility Criteria

The eligibility criteria were defined based on PICO research strategy for clinical practice based on scientific evidence.

3.5. Selection Criteria

The articles were screened based on title and abstract. Full text was then procured for the articles which fulfilled the inclusion criteria mentioned below. This review includes clinical trials and randomized control trials.

3.6. Selection fo Studies

3.6.1. Inclusion Criteria

- (1) Studies on patients undergoing fixed orthodontic treatment

- (2) Studies that used fluoride and chlorhexidine varnishes for the prevention and management of white spot lesions

- (3) Studies that used Pre-adjusted edgewise appliance (MBT system- conventional orthodontics)

- (4) Randomized control trials and clinical trials.

3.7. Risk of Bias Assessment in Individual Studies

Two independent authors assessed the risk of bias for all the studies included. Another author was asked for advice and the final decision was made. Randomized trials were assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB 2.0) tool, Higgins JPT 2016 which involves judgement on seven headings as formulated by the Cochrane Group [37]. The risk of bias for each of the domains and overall risk of bias were made as per the recommendations of the RoB 2.0 tool.

Trials were classified overall as having a low risk of bias, some concerns of bias or a high risk of bias as described in the RoB 2.0 tool. Non-randomized trials were assessed NewCastle - Ottawa quality assessment scale [38]. The risk of bias for each of the headings and overall risk of bias was made as per the recommendations of the ROBINS-I tool [39]. Trials were classified overall as having no information, low risk, moderate risk, serious risk or critical risk of bias.

3.8. Evaluation of the Levels of Evidence

The possible influence of small study publication biases on review findings was considered and formed a part of the GRADE level of evidence (GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool, available online at gradepro.org) [40, 41]. The influence of small study biases was addressed by the risk of bias criterion ‘study size’. Assessment of the quality of evidence was based on Oxford's CEBM table [42].

4. RESULTS

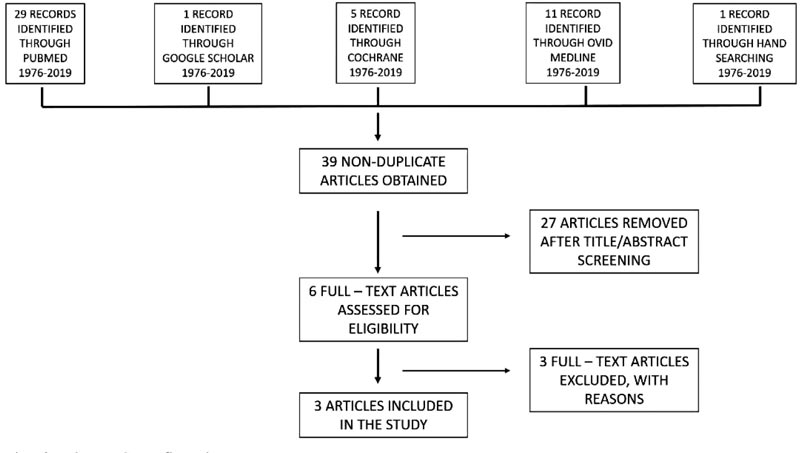

Three articles were selected based on the inclusion criteria. The PRISMA flow chart is given in Fig. (2). Out of these studies, all three were randomized control trials.

4.1. Reporting and Interpretation of Results

This systematic review included mainly randomized clinical trials. These studies were of high and medium quality. The results which were achieved and interpreted from these articles suggested that use of chlorhexidine varnish separately or together with fluoride varnish reduces the prevalence of white spot lesions within the patients undergoing treatment. Shiva Alavi et al. [43] in their study, stated that a statistically significant decrease of WSLs was registered in the participants of chlorhexidine and fluoride groups throughout the three follow-ups but not within the control or the placebo groups. There have been no significant differences observed between the chlorhexidine and fluoride groups for demineralization. The clinical detection of WSLs has been dispensed primarily by means of visual inspection after air drying and tactile examination by probing. The introduction of several optical techniques during recent decades, including optical caries monitor, use of quantitative laser and light induced fluorescence, digital imaging with fiber-optic transillumination, laser fluorescence, and computer analysis of digital photographs, are suggested for WSL detection. Because of simple sampling, the unification of DMFS (Decay-missing-filling-surfaces) was difficult in every study. Restrepo et al.. [44], in their study, suggested that the association of fluoride and CHX failed to lead significant reduction within the development of WSLs on the buccal surface, as compared with fluoride only. The interpretation of the null findings should not consider unfavorable results, but it should note the relevance of the patients’ motivation to require care of their oral health. However, that style of approach was 100% acceptable, justifying that the relevance of the findings showing the F varnish was able to accelerate the regression of active WSLs, and it may be indicated for patients who were unmotivated or with difficulties in performing adequate oral hygiene practices. Although the above-mentioned study attained its objectives, some limitations were found. The sample size was very small; thus, studies with an increased sample size are necessary to verify the results. Furthermore, future studies with an extended follow-up time, like the inclusion of more clinically relevant outcomes, besides DDpen that presents some limitations, must be conducted to verify whether any significant difference is observed between the treatments. Bjørn Øgaard et al. [45] studied stepwise multivariate and correlation analyses to comprehend whether WSL development may be predicted earlier during the treatment with fixed appliances. Very low correlations and associations were found between WSLs at debonding and several other parameters registered during treatment. It may well be demonstrated that those patients who had MS in plaque and far visible plaque in the teeth 12 weeks after bonding and were non-compliant during the treatment had a significantly higher prevalence of white spots at debonding. The analysis also showed that 15% of the variation in WSL might be explained by the registered parameters. This was in step with findings that caries are difficult to predict, even in non-orthodontic patients. Generally, past caries experience is the best predictor of future caries increments in non-orthodontic patients. Few individuals have lesions on the labial surfaces before bonding of orthodontic appliances. Therefore, visible plaque round the appliance shortly after bonding may indicate a risk for WSL development during treatment. This declaration is supported by the observation that, when fluoride toothpaste is applied regularly, oral hygiene is the most vital thing explaining the variation in caries experience. In the above-mentioned study, the antimicrobial varnish and a placebo varnish were applied every week for 3 weeks before bonding. The results also showed that intensive application of the antimicrobial or the placebo varnish before bonding reduced the extent of MS in plaque significantly which both were equally effective. During this intensive 3-week period, the amount of plaque and gingival scores also decreased significantly in both groups.

4.2. Description of Studies

This systematic review included three articles, all three being randomized control trials which comprised an evaluation of the effect of chlorhexidine and fluoride varnish on incidence of white spot lesions in patients undergoing orthodontic treatment and are described in Table 1.

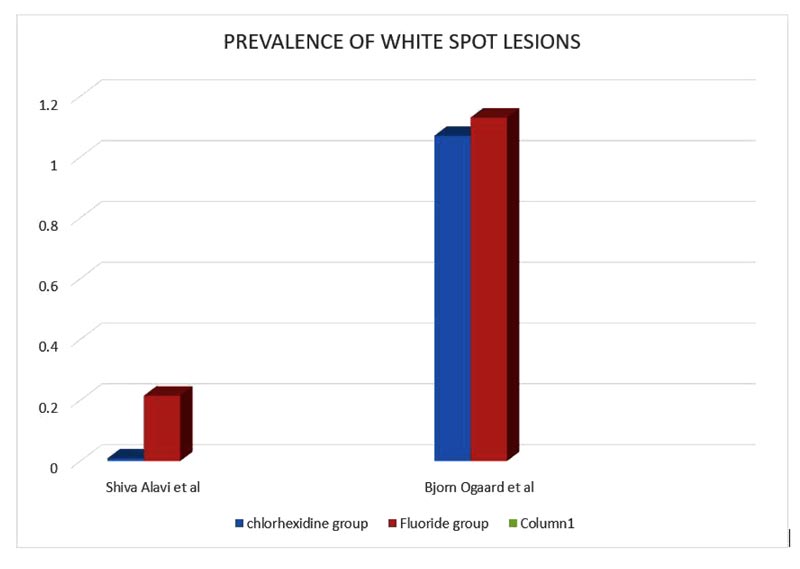

The summation table for each individual parameter is described in Table 2. The reduction shown in the prevalence of white spot lesions is described in Fig. (3).

| Sno |

Author Year of publication |

Type of Study | Study design | Samples | Age | Groups | Statistical Analysis | Author conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shiva Alavi et al. 2018 | In Vivo | Randomized controlled Trial | n=40 | 23 years (18-34) |

Group 1: Control Group 2: Chlorhexidine varnish Group 3: Fluoride varnish Group 4: Placebo |

Kruskal-wallis and Mann-Whitney tests | Adding CHX gel and fluoride varnish to a patient's oral hygiene regimen can reduce the development of plaque and gingivitis and decrease WSLs in patients. |

| 2 | Restrepo M et al. 2016 | In Vivo | Randomized controlled Trial | n=35 | 13-20 years | Group 1: 5% Fluoride varnish Group 2: 2%Chlorhexidine varnish Group 3: Control |

Repeated measures ANOVA and Tukey’s test | The treatment with F varnish was capable of controlling the progression of WSLs in a shorter period of time. |

| 3 | Bjørn Øgaard et al. 2001 | In Vivo | Randomized controlled Trial | n= 320 | 12-15 years | Group 1: Both Chlorhexidiene and Fluoride varnish Group 2: Fluoride varnish Group 3: Control |

Correlation analysis and Multiple regression analysis | Cervitec significantly reduced the number of MS in plaque during the first 48 weeks of treatment . This didn’t significantly reduce the number of WSLs. The combination varnishes worked more efficiently. |

| S. No | Author and year of publication | Prevalence of white spot lesion in chlorhexidine group | prevalence of white spot lesion in fluoride group |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Shiva Alavi et al. 2018 | 0.009 ± 0.01 | 0.215 ± 0.18 |

| 2. | Restrepo M et al. 2016 | 17 lesions have reduced to 7 lesions (mean and SD not mentioned) |

15 lesions have reduced to 2 lesions (mean and SD not mentioned) |

| 3. | Bjørn Øgaard et al. 2001 | 1.07 ± 0.15 | 1.13 ± 0.28 |

| S. No.- | Criteria | Shiva Alavi et al. | Restrepo M et al. | Bjørn Øgaard et al. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Study Design | - | - | - |

| A | Objective clearly formulated | YES | YES | YES |

| B | Sample size for each gender | YES | NO | NO |

| C | Sampling method clearly reported | YES | NO | NO |

| D | Inclusion criteria clearly reported | NO | YES | NO |

| II | Records taking process | - | - | - |

| E | Appropriate record materials stated | YES | YES | YES |

| F | Intervals at which records were taken were clearly mentioned | YES | YES | YES |

| III | Measurements | - | - | - |

| G | Measurement techniques clearly mentioned | YES | YES | YES |

| H | Definition of landmarks clearly defined | YES | YES | YES |

| I | Attempts to ensure quantity reliability | YES | YES | YES |

| IV | Statistical analysis | - | - | - |

| J | Statistical analysis appropriate for data | YES | YES | YES |

| K | Confidence intervals provided | NO | NO | NO |

| - | MODERATE | LOW | LOW |

4.3. Risk of Bias in the Included Studies

The risk of bias assessment for the studies included in the systematic review was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB 2.0) tool, Higgins JPT 2016 and is given in Table 3.

5. DISCUSSION

Varnish application was used as a method of prevention [46-54] and management [44, 55-59] of white spot lesions. Fluoride varnish was used for the prevention and management of white spot lesions [45, 53, 55, 60-63]. Application of ammonium fluoride around the bracket base every sixth week during orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances could prevent the development of advanced WSLs and this result reinforced the use of professional fluorides in orthodontic care [64]. Fluoride varnish containing CPP-ACP had good clinical success in reducing S. mutans count. Use of fluoride varnish containing CPP-ACP [65] and xylitol as a preventive intervention effectively prevents caries in children [66]. Professional topical fluoride application showed 25-30% reduction in the incidence of EWSLs after debonding, but the effect of professional fluoride application on complexity of EWSLs was unclear due to the concerns in interpreting DIAGOdent values to estimate EWSLs [67]

A varnish with 1% chlorhexidine and Thymol varnish (Cervitec plus) was used for the reduction in bacterial count [68-73] and for prevention and management [68, 74-79] of whitespot lesions. A study was conducted to compare the effect of single application and multiple application of varnish showed that multiple applications of Cervitec plus have an added benefit over the single application in the treatment of chronic periodontitis [80]. A study compared the effect of laser [81-84] and varnishes and stated that Er, Cr:YSGG laser can be recommended for cavity disinfection due to its superior antibacterial property [85]. A systematic review on Cervitec varnish had a weak level of evidence suggesting an effective antimicrobial property when Cervitec varnish is used against Streptococcus mutans [86]. Laser fluorescence using DIAGOdent [87-95] was used as a method for detection of white spot lesions and early caries on tooth surfaces [96-103].

The limitation of this systematic review is the use of a smaller number of randomized clinical trials which make the results obtained be a low-level evidence. The strength of this systematic review is that this is the only systematic review available on this topic studying the effect of chlorhexidine and fluoride varnish on the incidence of white spot lesions in orthodontic patients.

6. CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE

The need for an adjunct oral hygiene aid to reduce the incidence and prevalence of white spot lesions in orthodontic patients is necessary. The use of these varnishes will reduce the incidence of white spot lesion formation and in their management in the orthodontic patients, thus making one of the adverse effects of fixed orthodontic treatment to be negligible.

CONCLUSION

Low-level evidence is available to come to a conclusion that the use of chlorhexidine varnishes and fluoride varnishes reduces the prevalence of white spot lesions in patients undergoing fixed orthodontic treatment. But the current systematic review must be interpreted with caution because of the small number of participants and their short observation period.

Thus, high-quality randomized controlled trials with higher sample size and longer duration studies to evaluate the potential of these varnishes on the incidence and prevalence of white spot lesions are needed to have a definite conclusion.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and. or publication of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to acknowledge my colleagues and my professors for guiding me through the process of this systematic review.