All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

State of the Art Contemporary Prefabricated Fiber-Reinforced Posts

Abstract

Background:

There is an increased interest in investigating and use of prefabricated fiber-reinforced posts by scientists and clinicians in the restoration of endodontically treated teeth.

Objective:

The objective of this narrative review was to summarize the composition of contemporary prefabricated fiber-reinforced posts and elucidate its effect on the different properties of these posts.

Methods:

PubMed/Medline, Scopus, and Google Scholar were searched from January 1990 to December 2019 for English Language articles describing the composition and properties of prefabricated fiber-reinforced posts. First, the search strategy was established for Medline / PubMed using the following terms ((Fiber post[All Fields] OR (fiber reinforced post[All Fields] AND composition[All Fields] AND (“matrix”[MeSH Terms] OR (“fiber”[All Fields] AND “properties”[All Fields] AND “epoxy”[All Fields]) OR “dimethacrylate”[All Fields]) AND NOT (CAD CAM[All Fields])). The search strategy was then adapted for Scopus and Google Scholar databases to identify eligible studies.

Results:

The current state of the art of prefabricated fiber-reinforced posts revealed a myriad of products with different formulations which are reflected on the mechanical and handling characteristics of the different posts available in the market. More recent research and development efforts attempted to address issues related to the improved transmission of polymerization light through the post to the most apical end of the restoration inside the root canal. Others focused on the development of new matrix materials for fiber-reinforced posts.

Conclusion:

A review of the literature revealed that currently available prefabricated fiber-reinforced posts consist of a heterogeneous group of materials which can have a significant effect on the behavior of posts. Understanding different formulations will help clinicians in scrutinizing the vast literature available on prefabricated fiber-reinforced posts. This, in turn, will help them make an informed decision when selecting materials for the restoration of endodontically treated teeth.

1. INTRODUCTION

Although restoration of endodontically treated teeth is a daily clinical decision in restorative dentistry practice, there appears to be disagreement in recommendations regarding the selection of materials and techniques for their restorations [1, 2]. Loss of a large proportion of coronal tooth structure due to caries, previous restorations, and endodontic access cavity preparation, results in an increased need for the placement of intra-radicular posts during the restoration of endodontically treated teeth. Until the early 1990s, accepted methods to fabricate intra-radicular posts included custom-made cast metal posts and cores or prefabricated metal posts, made of stainless steel or titanium alloys, in combination with different core materials.

Originally clinicians believed that posts could reinforce the root canal treated teeth [3]. However, later studies have pointed out that posts do not strengthen teeth. In fact, these studies demonstrated that the preparation of a post space and the placement of a metal post can weaken the root and may lead to root fracture [4-7]. These and other studies have, therefore, suggested that a post should be used only when the remaining coronal tooth tissue can no longer provide adequate support and retention for the coronal restoration [8, 9].

Disadvantages of metallic posts such as the risk of corrosion, root fractures, loss of retention, coupled with increased demand for aesthetic restorations that necessitates placement of aesthetic posts underneath all ceramic crowns led to the development of posts made of aesthetic materials such as ceramic zirconia [10], fiber-reinforced composites [11], and polyetherketoneketone (PEKK) [12]. Among these, fiber-reinforced posts attracted the attention of researchers and clinicians alike, resulting in increased use of these posts in clinical situations. The increased demand for fiber-reinforced posts resulted in the development of an enormous variety of fiber-reinforced posts with different compositions. Studies have shown that different prefabricated fiber-reinforced posts exhibited variations with regard to mechanical properties [13, 14], ability to transmit polymerization light [15, 16], radiopacity [17], as well as interactions with different materials such as luting cements and composite core materials [11, 18].

Therefore, understanding the differences in the composition of the various prefabricated fiber-reinforced posts is essential for clinicians to be able to select appropriate materials for the restoration of endodontically treated teeth. Hence, the aim of this narrative review is to summarize the current knowledge on the composition of contemporary prefabricated fiber-reinforced posts.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

It is well accepted that systematic reviews follow a predetermined method to methodically search, select, appraise, synthesize, and analyze the literature [19]. As systematic reviews are designed to answer focused questions, they do not allow for a comprehensive insight of some topics particularly those tracing the development of a clinical concept [19-21], such as that of the current review on the different compositions of prefabricated contemporary fiber-reinforced posts. The question to be answered in this review was “what are the different formulations/compositions of prefabricated fiber-reinforced posts?”. To answer this, a narrative review was used to avoid losing valuable information that may occur as a result of the strict inclusion/exclusion criteria used in systematic reviews, thus allowing for the selection of relevant literature to the question.

For this review, the literature search was carried out using the electronic databases PubMed/Medline, Scopus, and Google Scholar from January 1990 to December 2019. The search strategy was first established for Medline via PubMed using the following terms: ((Fiber post[All Fields] OR (fiber reinforced post[All Fields] AND composition[All Fields] AND (“matrix”[MeSH Terms] OR (“fiber”[All Fields] AND “properties”[All Fields] AND “epoxy”[All Fields]) OR “dimethacrylate”[All Fields]) AND NOT (CAD CAM[All Fields])). The search strategy was then adapted for Scopus and Google Scholar databases to identify eligible studies. Additionally, hand searching of retrieved articles was also performed for further relevant publications. The search was limited to English language literature.

The articles screened were divided into relevant or nonrelevant for the present review based on the following inclusion criteria; 1) articles describing the composition of prefabricated fiber-reinforced posts, and 2) properties as related to the composition of prefabricated fiber-reinforced posts. Articles describing custom-made fiber posts and CAD-CAM made posts were excluded.

3. RESULTS

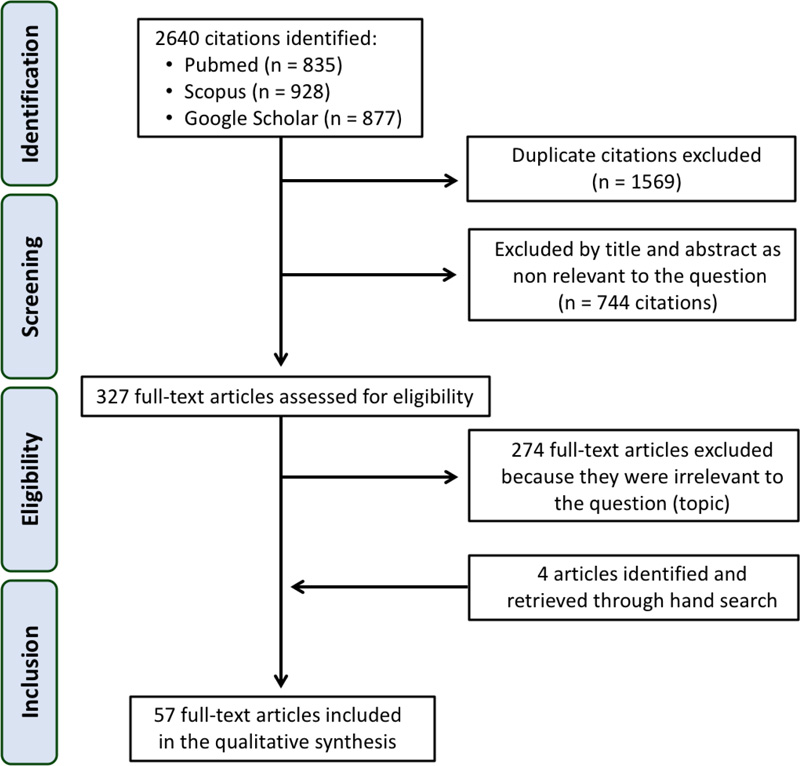

A total of 2640 articles were identified from the three electronic databases (Fig. 1). First, the identified articles were uploaded into a reference manager software library (Zotero, Corporation for Digital Scholarship, NY) and duplicate articles were excluded. The titles and abstracts of the remaining articles were then screened by two independent reviewers (T.A and H.E.E). Three hundred and twenty-seven articles satisfied the inclusion criteria and were selected for full-text reading. Following readings of full-text articles, 53 articles were selected. The inclusion of articles was based on discussions between the two reviewers. To assess consistency among the reviewers, the inter-reviewer reliability was calculated (Cohen’s Kappa Index Value 0.886 [95% CI 0.950; 0.82]; p = 0.001). Disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved through discussion with the third reviewer (E.S.E.). A hand search of the selected articles yielded further 4 articles that were considered pertinent to the topic. Ultimately, 57 articles [1-3, 5-18, 22-61] were included in this review.

Information from the selected articles was synthesized in this narrative review under the following headings; i) historical background, ii) advantages of fiber-reinforced posts, iii) composition of fiber-reinforced posts, and iv) conclusions, as described in the following sections.

4. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Fiber-reinforced posts introduced in the early 1990s [22]as an alternative to cast post-and-core metal posts [1, 23, 24]. The technology of fiber-reinforced posts development was based on the principles of fiber-reinforced acrylic and composites. The dental use of this technology started in the 1960s to strengthen acrylic base materials for removable partial dentures [25]. This was followed by the attempts to combine reinforcing fibers with dimethacrylate composite resin to be used for the fabrication of fixed partial dentures [26, 27].

The first introduced fiber-reinforced post, namely Composipost®, consisted of carbon/graphite fibers embedded in an epoxy resin matrix [22]. They were characterized by good mechanical properties, such as high stiffness and tensile strength, in addition to electrical conductivity and comparatively low toxicity [28, 29].

The main drawbacks of carbon fiber-reinforced posts were their black color limiting their use under all-ceramic and composite restorations in areas of high aesthetic demand, and their radiolucency, which made it difficult to identify these posts on radiographs due to the carbon content [30, 31]. These limitations of carbon fiber-reinforced posts led to the development of fiber-reinforced posts with more esthetic and radiopaque properties using silica fibers in the form of quartz or glass fibers embedded in a polymer matrix [30, 31].

5. ADVANTAGES OF FIBER-REINFORCED POSTS

It has been suggested that the most significant advantage of fiber-reinforced posts as compared to other metallic, or ceramic posts is their modulus of elasticity. Several authors believe that the similarity between the elastic moduli of fiber-reinforced posts and dentine will distribute the stress and less likely to cause root fracture in endodontically treated teeth as compared to metal posts [22, 32, 33]. The modulus of elasticity of glass fiber posts, however, has been shown to range from 20- 56 GPa [34, 35], which is relatively close to that of dentin (range between 18 - 20 GPa) as compared to that of cast metal alloy and prefabricated metal posts which range from 86 - 200 GPa [34]. Therefore, the elastic moduli of some prefabricated fiber-reinforced posts is about 2-3 times, whereas that of metal posts is about 4-10 times that of dentine [34].

The other advantage of fiber-reinforced posts is their ability to bond with most resin cements and resin-based composite core materials. Luting of the fiber-reinforced post to the dentinal wall with resin cement gives advantages like reducing the wedging effect of the post in root canal thus reducing the incidence of root fracture [36-38].

Fiber-reinforced posts also overcome limitations of metal posts like the possibility of corrosion and associated possible biocompatibility concerns that may trigger allergic reactions [39]. Furthermore, improved aesthetics of fiber-reinforced posts with glass or quartz fibers offered the most satisfactory visual properties which allowed the use of all ceramic crowns with improved aesthetics of the restored endodontically treated teeth [39]. Moreover, the use of fiber-reinforced posts simplified clinical procedures by eliminating the need for laboratory steps and facilitated re-treatment in cases of endodontic failure as a result of their easier removal techniques [39-41].

6. COMPOSITION OF FIBER-REINFORCED POSTS

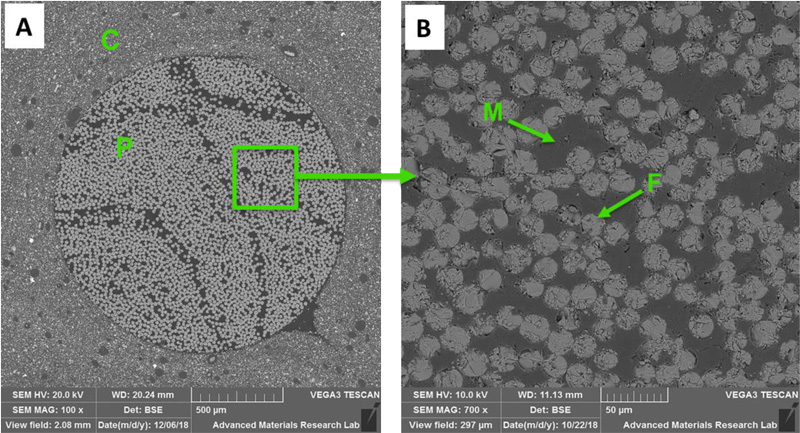

There is a myriad of commercially available fiber-reinforced posts on the market to choose from (Table 1). They are essentially composed of pre-stretched fibers bounded by a polymer resin matrix [11]. The different components of the fiber-reinforced post are shown in Figs. (2 and 3).

| Post | Composition | Shape | Manufacturer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matrix | Fiber | |||

| DT Light Post Illusion | Epoxy 40% | Quartz 60% | Double Tapered | RTD, Grenoble, France |

| DT Light Post | Epoxy 40% | Quartz 60% | Double Tapered | RTD, Grenoble, France |

| DT Light-Post Illusion X-Ro | Epoxy 40% | Quartz 60% | Double Tapered | Bisco, USA |

| Aestheti Plus | Epoxy 40% | Quartz 60% | Two-stage Taper | RTD, Grenoble, France |

| Macrolock Illusion Post | Epoxy40% | Quartz 60% wt. | Tapered, Circumferential head grooves, spiral head serration | RTD, Grenoble, France |

| Ellipson Post | Epoxy resin 36% | Quartz fiber 80% wt. | Tapered, Oval fiber post | RTD, Grenoble, France |

| Fibercone ‘The Accessory Post’ |

Epoxy resin | Quartz stretched fiber | Tapered shaft portion | RTD, Grenoble, France |

| Endo-Light Post | Epoxy40% | Quartz 60% vol. | Tapered | RTD, Grenoble, France |

| DT Illusion Xro Sl | Epoxy 40% | Quartz fiber 60% vol. | Double Tapered | VDW, Munich, Germany |

| DT Light | Epoxy 40% | Pre-conditioned Quartz fiber 60% wt. | Double Tapered | VDW, Munich, Germany |

| DT Light Safety Lock | Epoxy 40% (silica and silane coated) |

Quartz 60%wt, | Double Tapered | VDW, Munich, Germany |

| Relyx Fiber Post | Epoxy 30-40% Zirconia filler. |

Glass 60-70% | Double Tapered | 3M ESPE, St.Paul, MN, USA |

| Dentin Post X | Epoxy 40% | Glass 60% | Tapered with aretentive head, Coating layers of silicate, silane and polymer | Komet, Lemgo, Germany |

| Glass Fiber Reforpost | Epoxy 19% | Glass 80% Stainless steel lament 1% |

Parallel and Serrated | Angelus, Londrina, PR, Brazil |

| Exacto Translucent Fiber Post | Epoxy 20% | Glass 80% | Double Tapered | Angelus, Londrina, PR, Brazil |

| Reforpin ‘The Accessory Post’ |

Epoxy 20% | Glass 80% | Tapered | Angelus, Londrina, PR, Brazil |

| Glassix Fiber Post |

Epoxy 40% | Glass 60% | Parallel | Nordin, Montreux Switzerland |

| Glassix Plus Radiopaque & Light Transmitting Fiber Post |

Epoxy (ethoxyline) 25-35% | Glass 65-75% | Parallel | Nordin, Montreux Switzerland |

| Matchpost | Epoxy 40% | Glass 60% | Tapered apical section | RTD, Grenoble, France |

| Parapost Fiber White | Epoxy 29% | Glass 42%, Filler 29% | Parallel | Coltene/Whaledent Inc, USA |

| Parapost Fiber Lux | Epoxy 40% | Glass 60% | Parallel | Coltene/Whaledent Inc, USA |

| Parapost Taper Lux | Epoxy 40% | Glass 60% | Tapered | Coltene/Whaledent Inc, USA |

| Dentolic Glass Fiber Post | Epoxy 20% wt. | Glass 80% wt. | Double Tapered | Itena-Clinical, France |

| Ilumi Fiber Optic Post, | Epoxy 30% wt. | Reinforced optical glass fiber 70%, | Tapered | iLumi Sciences Inc, USA |

| Radix Fiber Post | Epoxy 40% | Zirconium enriched glass 60% | Double Tapered | Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland |

| Snowpost | Epoxy 40% | Glass (with 18% zirconia) 60% | Taper in the apical third | Carbotech, Ganges, France |

| Snowlight | Vinyl-polyestermethacrylate 35% | Glass (with 18% zirconia) 65% | Taper in the apical third | Carbotech, Ganges, France |

| Carbon Fiber Reforpost | Epoxy 21% | Carbon 79% | Parallel and Serrated | Angelus, Londrina, PR, Brazil |

| Composipost | Epoxy 36% | Carbon 64%vol. | Two-stage parallel | RTD, Grenoble, France |

| Carbonite | Epoxy 35% | Carbon 65%,(Carbon fiber braided plait) | Parallel | Nordin, Montreux Switzerland |

| C-Post | Epoxy 36% | Carbon 64%, Pyrolitic carbon fiber | Tapered | Bisco, USA |

| Carbopost | Epoxy 40% | Carbon 60% | Parallel | Carbotech, Ganges, France |

| Luxapost Fiber Post | Bis-GMA based resin | Glass fiber | Tapered | DMG, Hamburg, Germany |

| Fibrekor Fiber Post | Bis-GMA, HDDMA, UDMA, DEAMA 29% wt. Barium sulfate, barium silicate fillers. | Glass 71%wt., | Parallel and serrated | Pentron, Wallingford, CT, USA |

| Fibrekleer Serrated Post | BisGMA, UDMA, HDDMA 16-19% | Glass 81-84%wt. | Three types: parallel, tapered, and serrated | Jeneric/Pentron, Wallingford, CT, USA |

| Rebilda Post | Dimethacrylate 20% (UDMA) | Glass 70%, Filler 10% | Apical 8mm is taper, Coronal 10mm is parallel | Voco, Cuxhaven, Germany |

| FRC Postec Plus | Dimethacrylate 21% (UDMA, TEGDMA). Ytterbium trifluoride 9%, highly dispersedsilicon dioxide) | Glass 70%, | Tapered | Ivoclar-Vivadent, Schaan, Liechenstein |

| GC Fiber Post | Methacrylate 42% | Glass 58% | Double Tapered | Tokyo, Japan |

| Everstick Fiber Post | Semi IPN PMMA and Bis-GMA | Glass 61.5% wt. | Unidirectional fiber bundle | GC, USA |

6.1. Matrices used in Fiber-reinforced Posts

The functions of the matrix in fiber-reinforced posts are to hold the fibers together in the post, as well as interact with functional monomers contained in the adhesive cements for successful bonding of post to root dentine and to composite core materials [31]. Furthermore, the matrix transfers stresses between fibers and protects fibers from the outside environment such as chemicals, moisture, and mechanical shocks [42]. Thus, the matrix may influence the compressive strength of the post, as well as interlaminar shear properties between the matrix and the fiber [42].

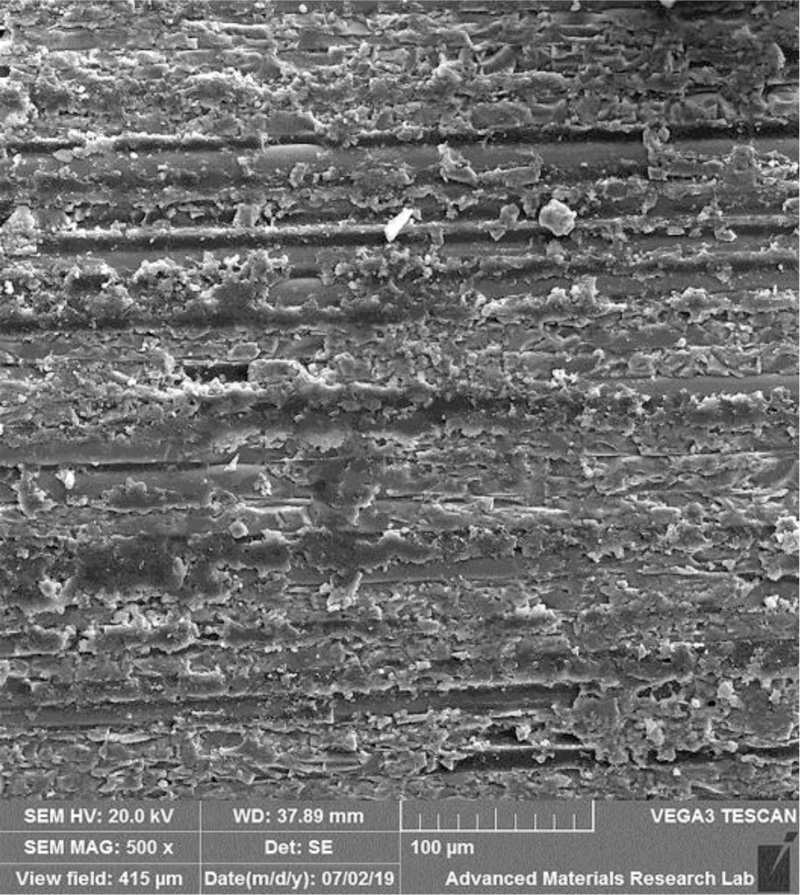

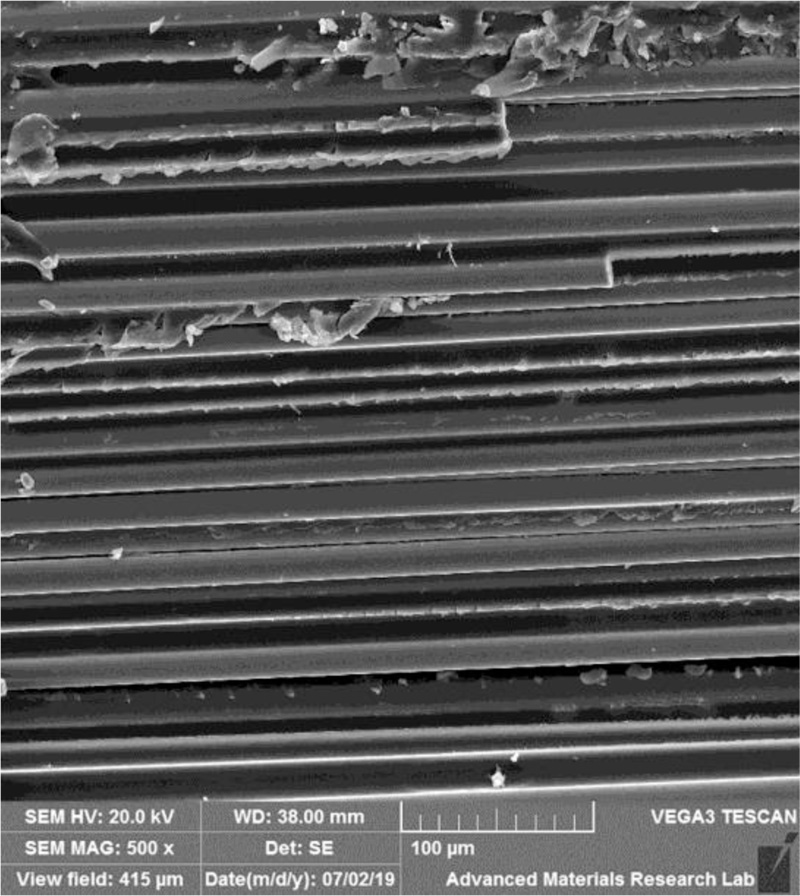

During the manufacturing of fiber-reinforced posts, glass or quartz fibers are pre-stretched and treated with silane coupling agent before they are impregnated in the resin matrix [43]. The resin-impregnated fibers are then heat cured to form blocks of different shapes and diameters. Finally, the blocks are shaped into posts with different geometries and diameters through a milling process [44]. As a result of the milling process, some of the fibers are exposed onto the surface of the prefabricated posts (Fig. 4).

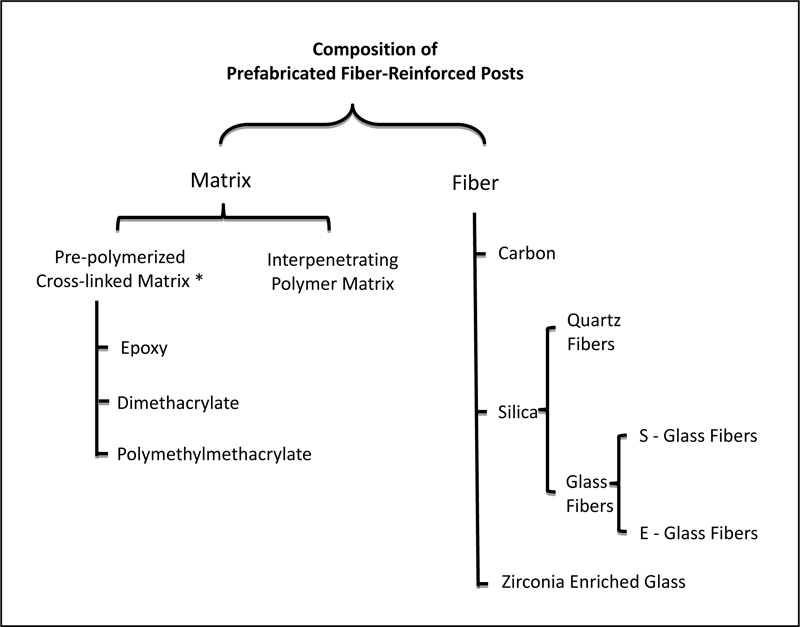

Two major types of matrices are used in prefabricated fiber-reinforced posts. The first type consists of a highly cross-linked polymer matrix polymerized by the manufacturers, while the second type consists of unpolymerized, the so-called interpenetrating polymer matrix where the dentist can polymerize it during the fabrication of the post-core restoration [11].

The most common types of matrices used in the polymerized cross-linked fiber-reinforced posts are epoxy-based or diamethacrylate-based cross-linked matrix. Less commonly, some manufacturers use polymethylmethacrylate-based resin matrix for their posts. Additionally, some investigators have suggested the use of aromatic polyimides as a matrix for fiber-reinforced posts [45].

Epoxy resin are thermosetting polymers, also known as polyepoxide, that are formed by the reaction of the base epoxide with the reactor polyamine [46]. On the other hand, the aromatic monomer Bis-GMA (bisphenol A glycidyl methacrylate) used widely as a matrix in dental composite resin materials have also been used as a matrix in fiber-reinforced posts. Bis-GMA matrix is known to be stiffer than the epoxy matrix [47]. As a result, flexural strength tests have shown that Bis-GMA-based matrix to experience greater stresses than epoxy-based matrix in fiber-reinforced posts [47]. Only a few manufacturers use polymethylmethacrylate of high molecular weight (> 220 KDa) as a matrix for fiber-reinforced posts [48].

The wide use of carbon-reinforced polyimide composite materials in aerospace and automobile industries has triggered researchers to investigate the possible use of these materials in fiber-reinforced posts [49]. Fiber-reinforced aromatic polyimides have been shown to have high strength and stiffness, lower density, high fatigue endurance, low thermal coefficient, and the ability to withstand extreme temperature changes [49, 50].

Gao and colleagues demonstrated that polyimide-based resin reinforced by high strength carbon fibers have good mechanical and biological properties and suggested its use in clinical situations [45]. Recently, Yang and Xu [51] found that blending polyimide and epoxy polymers have favorable mechanical properties and suggested its use as a matrix for fiber-reinforced posts. However, no fiber-reinforced post with polyimide matrix has been marketed.

6.2. Fibers used in Fiber-reinforced Posts

As it has been already alluded to, original fibers used in fiber-reinforced posts were made of carbon [22, 28]. As these carbon fibers did not fulfill aesthetic requirements under all-ceramic restorations, manufacturers developed more aesthetic fibers made of silica. Silica-based fibers can be either glass or quartz [30, 31]. The incorporated glass or quartz fibers imparted similar biomechanical properties, as carbon-fiber-reinforced posts, including elasticity, high tensile strength, low electrical conductivity, resistance to solubility and biochemical degradation [31,39,52]. On the other hand, some manufacturers used zirconia enriched glass fibers [15].

Due to their favorable mechanical properties and transparent appearance, glass fibers had become the most commonly used fibers in fiber-reinforced posts [46]. Based on their chemical composition there are several types of glass fibers available including A-glass (Alkali glass), C-glass (chemically resistant glass), D-glass (dielectric glass), R-glass (resistant glass), S-glass (high strength glass), and E-glass (electric glass) among others [42]. However, the most common types used in fiber-reinforced posts are the S-glass and E-glass fibers [46]. S-glass is known to have higher tensile strength and is rather expensive to produce, whereas E-glass has good tensile and compressive strength, as well as electrical properties and lower production cost [42]. However, E-glass has lower tensile modulus and lower fatigue resistance resulting in relatively poor impact resistance as compared to S-glass [42]. On the other hand, quartz fibers made out of pure silica in crystallized form, which is an inert material with a low coefficient of thermal expansion, has been used in several commercial fiber-reinforced posts [29] as seen in Table 1.

In addition to the types and properties of individual fibers, other fiber-related factors can affect the mechanical properties that may affect the clinical success of fiber-reinforced posts [42]. These include fiber orientation, fiber density, impregnation of fibers with the matrix polymer, and adequate adhesion of fibers to the matrix polymer [53, 42].

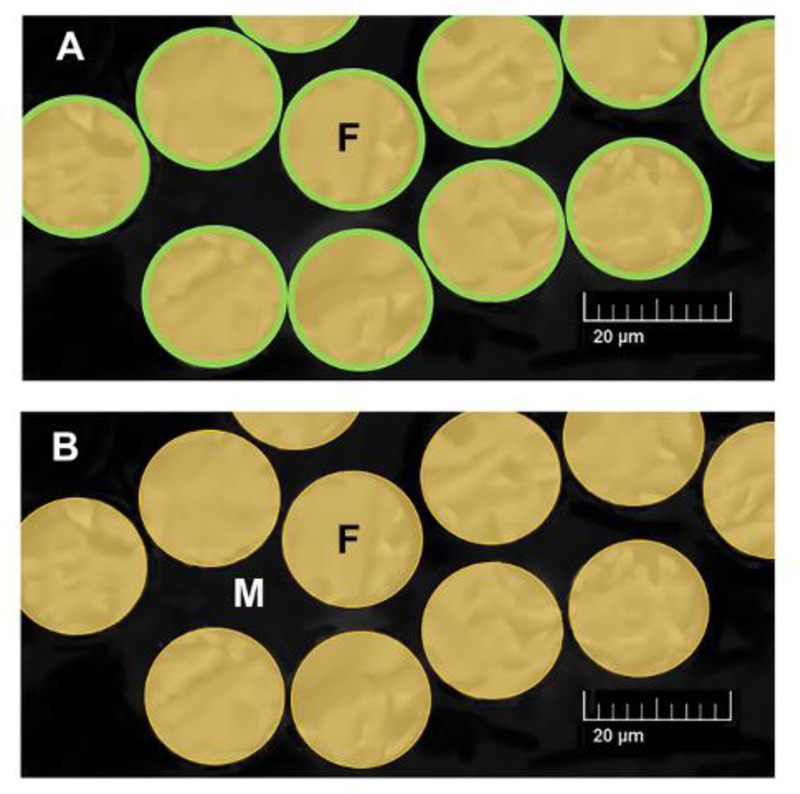

In fiber-reinforced posts, continuous unidirectional fibers are used [53]. Fibers direction influences the mechanical properties of fiber-reinforced posts [54]. The fibers are continuous and oriented parallel to the post longitudinal axis Fig. (5) with different diameters ranging from 6.0 to 21.0 microns [42, 48]. Fibers density (i.e. the number of fibers per mm2 of the post-cross-sectional surface) usually provided by the manufacturers’ and is expressed by weight or volume and varies from one brand to the other. Increased fiber density improves the strength and load-bearing capacity of fiber-reinforced posts [53]. In a transverse section of the post 30-50% of the area is occupied by fibers [30, 55] with fibers of smaller diameter allowing higher packing density of up to 70%.

The fibers should be well impregnated, meaning that resin should come in contact with the surface of every fiber, in order to achieve adequate adhesion of the fibers to the polymer matrix [53]. With good impregnation, optimal reinforcement and transfer of stresses from the polymer matrix to the reinforcing fibers are achieved [42]. During the fabrication of posts, fibers are pre-stressed, and resin injected under pressure to fill the spaces between the fibers, giving them solid cohesion [56]. The smaller the diameter of the fiber filaments the better the matrix ability to spread between the fibers leading to an increase in interlaminar tightness [48]. In addition, fibers are pre-coated with silane in order to improve the adhesion at the fiber-resin matrix interface [42, 56]. This also protects the fibers from damage during handling, modifying the catalytic and wettability properties of fiber surfaces so that their chemical resistance increased [57].

A durable adhesion between fibers and matrix of posts ensures that the load is transferred to the stronger fibers, thus optimizing the function of fibers as the reinforcing component of fiber-reinforced posts. On the other hand, if adhesion is not so durable and if any voids appear between the fiber and the matrix, these voids may act as initial fracture sites that encourage the breakdown of the material [42]. Differences in the coefficient of thermal expansion between fibers and resin matrix may affect the structural integrity of the post following thermal fluctuations in the mouth. There are large variations in the coefficient of thermal expansion between the polymer matrix (40-80 X10-6/°C) and that of E-glass (8 X10-6/°C), quartz (0.2 X10-6/°C), and carbon (0.4 X10-6/°C) fibers [29]. It has been shown that thermocycling decreased the flexural modulus of different fiber posts by approximately 10% [29]. This suggests that the mismatch in the coefficient of thermal expansion between fibers and matrix polymers might affect the long-term integrity of fiber posts.

Studies reported that post debonding is the most common type of failure seen in teeth restored with prefabricated fiber-reinforced posts [58]. In vitro studies have shown that the bond strength of luted fiber-reinforced posts was significantly lower in the apical third of canals followed by the middle third as compared to a coronal third of root canals [28, 59]. In fact, various fiber-reinforced posts have been shown to reduce the transmission of polymerization light intensity differently as light travels from the coronal toward the apical third of root canals [15].

The difference in light transmission between different fiber-reinforced posts can be attributed to differences in type and number of fibers, as well as the diameter and orientation of fibers [15]. In addition, the refractive index of the matrix used which can be influenced by factors such as the type of monomer, pigments, and fillers used can also affect absorption and scattering of light transferred to various depths of posts in the root canals [60]. Recently a novel fiber-reinforced post (iLumi fiber optic post; iLumi Sciences), was introduced into the market with the premise that it is able to transmit light to the most apical parts of the canal, thus improving the retention of the post and reducing the debonding rate [61]. In the iLumi fiber optic post, each fiber is thermally coated with optical glass cladding made of a non-corrosive, biocompatible material, the exact nature of which is kept confidential by the manufacturer (Fig. 6). This monolayer around each fiber is believed to force the light to be internally reflected and transmits to the apical end of the post. Studies have shown that this results in complete polymerization of resin cement as compared to other types of translucent fiber-reinforced posts [61]. While manufacturers claim that this resulted in increased bond strength of the apical third of luted iLumi fiber optic post, this has not been independently demonstrated.

It is highly desirable that posts cemented in root canals be visible on radiographs for evaluation and follow up. Therefore, prefabricated posts should have radiopacity similar to or close to that of root dentine. Studies have shown that different types of prefabricated fiber-reinforced posts exhibited different radiopacity levels. The composition of the post appears to be the most significant factor affecting the radiopacity of prefabricated fiber-reinforced posts [17]. Elements that appear to affect the radiopacity of the prefabricated fiber-reinforced post include silicon (Si), which may present in the form of silica, as well as zirconia (Zr), barium (Ba), and aluminum (Al) [17]. Differences in percentages of the various radiopaque elements, their atomic number, and crystallization forms seem to affect the radiopacity from one type of fiber-reinforced to the other [17]. These elements can be present in the fibers, matrix and/or added as fillers in some commercially available prefabricated fiber-reinforced posts.

CONCLUSION

Increased interest in the use of prefabricated fiber-reinforced posts resulted in the development of an enormous number of prefabricated cross-linked fiber-reinforced posts with different compositions, geometries, and properties. Understanding the composition of the different prefabricated fiber-reinforced posts available will aid clinicians in understanding the vast literature on the topic and help in their selection for clinical use. While the exact composition of the different prefabricated fiber-reinforced post is kept confidential by the manufacturers, the basic composition consists of pre-stretched fibers embedded in a resin polymer matrix. The functions of the different components and how they influence each other was discussed.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

FUNDING

This work was supported by research grant [No. 2018-A-DN-03] from Ajman University, Ajman, United Arab Emirates.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.