All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Effects of Mandibular Protraction Appliance and Jasper Jumper in Class II Malocclusion Treatment

Abstract

Objective:

This study aimed to compare the effects of Mandibular Protraction Appliance (MPA) and Jasper Jumper (JJ), associated with fixed orthodontic appliances for Class II malocclusion treatment.

Materials and Methods:

Sample comprised of 71 subjects, divided into 3 groups: Group 1: 24 patients, mean initial age 12.36 years, treated with MPA for 2.74 years; Group 2: 25 patients, mean initial age 12.72 years, treated with JJ for 2.15 years; Control Group: 22 subjects, mean age of 12.67 years, with untreated Class II malocclusion, followed for 2.12 years. Initial and final variables and treatment changes were compared between groups by ANOVA and Tukey tests.

Results:

JJ group presented greater restriction of growth and maxillary retrusion and MPA showed a greater increase of mandibular effective length. MPA and JJ groups showed improvement of maxillomandibular relationship. Maxillary incisors showed greater retrusion and retroclination in MPA group. MPA presented greater proclination of mandibular incisors and JJ showed greater protrusion. MPA and JJ groups presented a decrease in overbite and overjet.

Conclusion:

MPA showed a significant increase in mandibular effective length and great dentoalveolar compensation. JJ showed significant restriction of maxillary anterior displacement and also important dentoalveolar compensations. JJ must be indicated mainly in cases with maxillary protrusion, and MPA, especially in cases with mandibular deficiency.

1. INTRODUCTION AND STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

The current tendency for nonextraction treatment of Class II malocclusion is the use of appliances that do not need patient compliance, including fixed functional orthopedic appliances [1, 2]. Herbst appliance and its variations are the most used and investigated in the last years. Its main effects in Class II treatment are: Restriction of the anterior displacement of the maxilla, significant mandibular protrusion, distalization of maxillary molars, extrusion and retrusion of maxillary incisors, anterior movement of mandibular teeth in alveolar bone, intrusion of mandibular incisors, besides a significant improvement in maxillomandibular relationship [3, 4]. However, the Herbst appliance has a relatively high cost.

The Jasper Jumper appliance, more recently developed, had similar effects to the Herbst appliance, at a lower cost [1]. In 1995, Coelho Filho [5] developed the Mandibular Protraction Appliance, that consists of a simple mechanism that maintains continuous mandibular advancement and is constructed by the clinicians at a low cost. Some studies have demonstrated the efficacy of this appliance in correcting Class II malocclusion [5-10].

The Mandibular Protraction Appliance (MPA) and Jasper Jumper (JJ) are indicated for skeletal Class II malocclusion, mainly due to mandibular retrusion, and their main difference is rigidity. The effects of the MPA have not been compared with other fixed functional appliance, especially the JJ, to demonstrate the different effects in the correction of Class II malocclusions. Therefore, the objective of this study was to cephalometrically compare the dentoskeletal and soft-tissue changes after treatment of Class II malocclusions with MPA and JJ, associated with fixed appliances. The null hypothesis tested was: There are no differences between the effects of the MPA and JJ appliances in the Class II treatment.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Materials

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee in Human Research of the Bauru Dental School, University of São Paulo, Bauru, SP, Brazil. All patients signed informed consent.

The sample comprised of 71 subjects, divided into three groups. The primary selection criteria for the groups were a Class II Division 1 malocclusion with at least a bilateral half-cusp Class II molar relationship, all maxillary and mandibular teeth up to the second molars, a convex facial profile, and an accentuated overjet.

Group 1 comprised 24 patients (12 male; 12 female), at a mean age of 12.36 years (S.D =1.75), treated with MPA at a private clinic, for 2.74 years (S.D = 0.70).

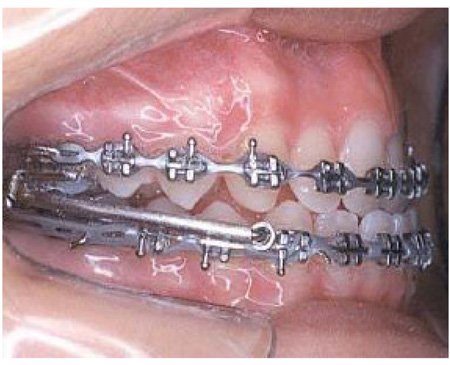

Patients from group 1 used the MPA in conjunction with fixed appliances (Fig. 1). The MPA is an intraoral fixed functional appliance developed by Coelho Filho [5] in 1995, that induces continuous mandibular protrusion to correct Class II malocclusions. It requires stainless steel rectangular archwires in both arches. The length of the appliance is determined by the distance from the mesial aspect of the maxillary tube to the stop on the mandibular archwire. Previous use of fixed orthodontic appliances is indispensable. Before placement of the MPA, 0.022 x 0.028-in fixed appliances were placed, and leveling progressed up to rectangular 0.021 x 0.025-in stainless steel archwires. Then the MPA was placed to correct the Class II anteroposterior discrepancy. The rectangular arches must have enough extension distal to the molar tubes for the bend-down tieback and to support elastic chains [5]. The mandible was advanced to an edge-to-edge incisor position.

Group 2 consisted of 25 patients (13 male; 12 female), at a mean age of 12.72 years (S.D = 1.20), treated with JJ [11] for 2.15 years (S.D = 0.29). These patients were treated in the orthodontic graduate clinic at Bauru Dental School, University of São Paulo, Bauru, SP, Brazil.

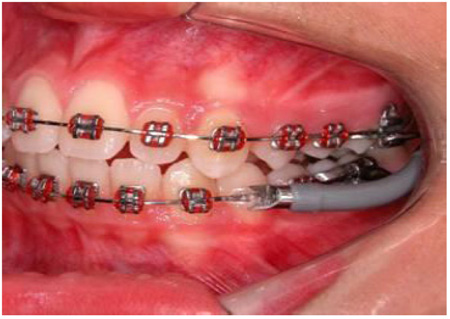

Patients from group 2 used the JJ appliance in conjunction with fixed appliances (Fig. 2). Before placement of the JJ, 0.022 x 0.028 in fixed appliances were placed, and leveling progressed up to rectangular 0.019 x 0.025 in stainless steel archwires. The Jasper Jumper (JJ) is a functional appliance for mandibular protraction (American Orthodontics, Sheboygan, USA). The mandibular arch was tied back to the first or second molars. In the maxillary arch, the jumper was attached to the headgear tube of the first molars as prescribed by the manufacturer with a ball-pin attachment. In the mandibular arch, the jumper was attached into the rectangular 0.019 x 0.025 in stainless steel archwire with a ball-pin attachment over the mandibular canine bracket from the distal side. JJ was selected according to the manufacturer’s instructions (American Orthodontics, Sheboygan, USA). The patients were seen every 4 weeks, and the appliances were activated every 8 weeks.

In both groups, functional appliances were removed when a Class I or overcorrected Class I canine and molar relationship was achieved. Finishing of the occlusion was obtained with fixed appliances. Retainers consisted of Hawley plates in the maxillary arches and bonded canine-to-canine lingual arches in the mandibular arches.

The Control Group comprised 22 subjects (12 male; 10 female), at a mean age of 12.67 years (S.D = 0.75), with untreated Class II malocclusion, observed for a mean period of 2.12 years (S.D = 1.63). These subjects were obtained from the files of Bauru Dental School, University of São Paulo, Bauru, SP, Brazil.

2.2. Methods

Two lateral cephalograms of each subject were used. Lateral cephalograms were manually traced, landmarks were digitized by a single investigator (RPH) and measurements were obtained with Dentofacial Planner 7.02 (Dentofacial Planner Software, Toronto, Ontario, Canada), which corrected the radiographic magnification (6 and 9.8%).

Variables included maxillary skeletal component, mandibular skeletal component, maxillomandibular relationship, vertical component, maxillary dentoalveolar component, mandibular dentoalveolar component and dental relationships. The mandibular effective length was considered the measurement of the variable Co-Gn in millimeters.

2.3. Error Study

After a month interval from the first measurement, thirty randomly selected cephalograms were retraced and re-measured by the same examiner (RPH). Casual errors were calculated according to Dahlberg’s formula [12], and the systematic errors were evaluated with dependent t tests [13], for P <.05.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Intergroup compatibility of sex distribution and severity of malocclusion were performed by Chi square tests. Intergroup compatibility of ages and treatment/observation time were performed by ANOVA test.

Initial variables and treatment changes were compared between the groups by ANOVA and Tukey tests.

All statistical analyses were performed with Statistica software (Statistica for Windows, Release 7.0, Copyright Statsoft Inc., 2005). Results were considered significant for P < 0.05.

3. RESULTS

The casual errors varied from 0.25 mm (Molar Relationship) to 0.94 mm (6-GoMe) and from 0.41º (ANB) to 1.47º (1.NB). Only two angular variables (IMPA and 1.NB) presented statistically significant systematic errors.

The three groups were compatible regarding the initial and final ages and time of evaluation (Table 1), sex distribution (Table 2) and initial severity of Class II molar relationship (Table 3).

|

Variables (Years) |

Group 1 MPA (n=24) |

Group 2 Jasper Jumper (n=25) |

Control Group (n=22) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean(S.D) | Mean(S.D) | Mean(S.D) | ||

| Initial Age | 12.36(1.75) | 12.72(1.20) | 12.67(0.75) | 0.606 |

| Final Age | 15.10(1.50) | 14.87(1.20) | 14.79(1.70) | 0.869 |

| Evaluation time | 2.74(0.70) | 2.15(0.29) | 2.12(1.63) | 0.065 |

|

Gender Groups |

Masculine | Feminine | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1- MPA | 12 (50%) | 12 (50%) | 24 (100%) |

| 2- Jasper Jumper | 13 (52%) | 12 (48%) | 25 (100%) |

| Control | 12 (54.5%) | 10 (48.5%) | 22 (100%) |

| Total | 37 (52.1%) | 34 (47.9%) | 71 (100%) |

| X2= 0.09 | DF=2 | P=0.953 | |

|

Class II Groups |

1/2-cusp | 3/4-Cusp | Full-Cusp | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1- MPA | 7 (29.17%) | 5 (20.83%) | 12 (50%) | 24 (100%) |

| 2- Jasper Jumper | 4 (16%) | 9 (36%) | 12 (48%) | 25 (100%) |

| Control | 10 (45.45%) | 5 (22.73%) | 7 (31.82%) | 22 (100%) |

| Total | 21 (29.57%) | 19 (26.76%) | 31 (43.67%) | 71 (100%) |

| X2= 5.71 | DF=4 | P=0.221 | ||

At pretreatment stage, MPA group presented significantly greater maxillary protrusion, a smaller mandibular effective length and a more protruded mandible, when compared to the other groups (Table 4). The control group presented slighter anteroposterior discrepancy (ANB, Wits) when compared to the experimental groups (Table 4). The MPA group had more buccally tipped maxillary incisors and greater overjet, in relation to the other groups (Table 4). The control group presented a significantly smaller Class II molar relationship (Table 4).

The JJ group presented greater restriction of growth and anterior displacement of the maxilla and greater maxillary retrusion and the MPA group showed a significantly greater increase of mandibular effective length (Table 5). Both experimental groups showed significant improvement in maxillomandibular relationship in relation to the control group (Table 5). The maxillary incisors presented greater retrusion and palatal inclination in the MPA than the other groups (Table 5). The MPA group presented greater labial inclination and the JJ group showed greater protrusion of the mandibular incisors than the control group (Table 5). The MPA and JJ groups presented a decrease in overbite and overjet relative to the control, and the MPA group had greater overjet decrease also in relation to the JJ group (Table 5).

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Pretreatment Comparison

MPA group showed a more protrusive maxilla in relation to the JJ and control groups. The mandible presented a smaller effective length in MPA group, when compared to JJ and control groups. This could be because subjects in MPA group were younger in the pretreatment stage than the other groups' individuals, in spite of not statistically significant.

| Variables |

Group 1 MPA (n=24) |

Group 2 Jasper Jumper (n=25) |

Control Group (n=22) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean(S.D) | Mean(S.D) | Mean(S.D) | ||

| Maxillary Skeletal Component | ||||

| SNA (º) | 84.59 (4.57)A | 82.60 (3.36)A | 81.93 (3.15)A | 0.051 |

| Co-A (mm) | 84.37 (3.68)A | 85.34 (4.44)A | 86.01 (4.65)A | 0.425 |

| A-Nperp (mm) | 3.76 (2.68)A | 1.17 (3.80)B | 1.19 (2.85)B | 0.007* |

| Mandibular Skeletal Component | ||||

| SNB (º) | 78.18 (3.32)A | 77.30 (2.39)A | 77.70 (3.76)A | 0.628 |

| Co-Gn (mm) | 102.59 (4.52)A | 106.30 (4.99)B | 106.04 (6.09)B | 0.028* |

| P-Nperp (mm) | -1.53 (4.05)A | -4.83 (4.89)B | -3.35 (4.33)AB | 0.040* |

| Maxillomandibular Relationship | ||||

| ANB (º) | 6.39 (2.78)A | 5.30 (3.06)AB | 4.23 (1.97)B | 0.028* |

| Wits (mm) | 2.42 (2.62)A | 1.62 (2.45)A | -0.45 (2.43)B | 0.000* |

| Vertical Component | ||||

| FMA (º) | 22.58 (5.24)A | 24.62 (3.92)A | 23.80 (2.72)A | 0.227 |

| SN.GoGn (º) | 30.17 (4.85)A | 31.12 (4.05)A | 30.86 (4.76)A | 0.756 |

| LAFH (mm) | 57.72 (5.77)A | 61.27 (4.93)A | 59.75 (4.10)A | 0.051 |

| Maxillary Dentoalveolar Component | ||||

| 1.PP (º) | 120.19 (6.12)A | 110.63 (7.11)B | 113.26 (5.60)B | 0.012* |

| 1-PP (mm) | 25.18 (3.28)A | 25.95 (4.48)A | 25.97 (2.57)A | 0.686 |

| 1.NA (º) | 29.01 (6.60)A | 23.95 (7.50)B | 23.27 (6.53)B | 0.010* |

| 1-NA (mm) | 4.97 (2.20)A | 4.49 (2.86)A | 3.32 (1.94)A | 0.063 |

| Mandibular Dentoalveolar Component | ||||

| IMPA (º) | 96.98 (7.90)A | 97.66 (7.39)A | 94.77 (4.68)A | 0.333 |

| 1.NB (º) | 27.39 (8.21)A | 28.22 (5.80)A | 25.58 (5.01)A | 0.375 |

| 1-NB (mm) | 4.36 (2.59)A | 4.98 (2.11)A | 3.94 (1.54)A | 0.252 |

| 1-PM (mm) | 36.39 (3.19)A | 38.18 (2.83)A | 37.18 (2.57)A | 0.100 |

| Dental Relationships | ||||

| Overjet (mm) | 8.40 (2.55)A | 6.14 (2.30)B | 4.68 (1.52)B | 0.000* |

| Overbite (mm) | 4.81 (2.00)A | 4.99 (1.69)A | 4.78 (1.73)A | 0.910 |

| Molar Rel. (mm) | -1.39 (1.54)A | -1.33 (1.22)A | 0.71 (1.13)B | 0.000* |

| Variables |

Group 1 MPA (n=24) |

Group 2 Jasper Jumper (n=25) |

Control Group (n=22) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean(S.D) | Mean(S.D) | Mean(S.D) | ||

| Maxillary Skeletal Component | ||||

| SNA (º) | -0.83 (3.35)AB | -1.42 (2.31)A | 0.73 (2.59)B | 0.030* |

| Co-A (mm) | 2.81 (2.13)A | 0.58 (2.20)B | 2.95 (2.59)A | 0.000* |

| A-Nperp (mm) | -0.25 (2.24)AB | -1.28 (2.89)A | 0.78 (3.29)B | 0.049* |

| Mandibular Skeletal Component | ||||

| SNB (º) | 1.04 (2.61)A | 0.02 (1.07)A | 0.48 (2.19)A | 0.222 |

| Co-Gn (mm) | 7.14 (3.57)A | 4.17 (2.91)B | 4.11 (3.55)B | 0.002* |

| P-Nperp (mm) | 2.32 (2.90) A | -0.06 (4.34) A | 0.92 (4.97) A | 0.138 |

| Maxillomandibular Relationship | ||||

| ANB (º) | -1.88 (1.75)A | -1.42 (1.67)A | 0.23 (1.36)B | 0.000* |

| Wits (mm) | -2.13 (2.28)A | -1.72 (3.10)A | 1.15 (2.29)B | 0.000* |

| Vertical Component | ||||

| FMA (º) | -0.73 (2.20)A | 0.78 (2.62)A | -0.02 (1.91)A | 0.073 |

| SN.GoGn (º) | -0.56 (3.06)A | 0.70 (1.83)A | -0.28 (2.30)A | 0.172 |

| LAFH (mm) | 3.21 (2.44)A | 4.30 (2.65)A | 2.86 (2.58)A | 0.138 |

| Maxillary Dentoalveolar Component | ||||

| 1.PP (º) | -10.81 (8.04)A | 0.54 (17.22)B | 0.31 (3.45)B | 0.000* |

| 1-PP (mm) | 1.25 (2.07)A | 2.18 (3.71)A | 0.61 (1.17)A | 0.121 |

| 1.NA (º) | -10.69 (8.83)A | -1.62 (8.35)B | -0.60 (3.58)B | 0.000* |

| 1-NA (mm) | -2.82 (2.95)A | -0.61 (3.03)B | -0.21 (1.31)B | 0.001* |

| Mandibular Dentoalveolar Component | ||||

| IMPA (º) | 4.57 (9.02)A | 2.43 (5.95)A | -0.10 (4.14)A | 0.070 |

| 1.NB (º) | 5.18 (8.25)A | 3.28 (5.75)AB | 0.39 (4.36)B | 0.044* |

| 1-NB (mm) | 0.95 (1.49)AB | 1.63 (1.56)A | 0.38 (1.54)B | 0.024* |

| 1-GoMe (mm) | 0.28 (2.67)A | 0.47 (1.32)A | 1.51 (1.99)A | 0.105 |

| Dental Relationships | ||||

| Overjet (mm) | -5.64 (2.54)A | -3.70 (2.38)B | -0.08 (1.39)C | 0.000* |

| Overbite (mm) | -2.21 (1.84)A | -2.90 (1.33)A | -0.60 (1.90)B | 0.000* |

| Molar Rel.(mm) | 3.81 (1.94)A | 3.42 (1.18)A | -0.24 (1.42)B | 0.000* |

JJ group showed a more retruded mandible when related to MPA group. This could be explained because JJ is the group with more vertical growth pattern, despite without a significant difference.

MPA group presented the worst maxillomandibular relationship followed by the JJ group and then the control group. This was expected since the control group presented a smaller Class II molar relationship severity. However, despite these limitations, other studies have also used control groups with milder Class II characteristics than the experimental group [14-17].

MPA group presented more buccally tipped maxillary incisors as compared to the other groups. MPA group showed a greater overjet in relation to the JJ and control groups and the MPA and JJ presented more severe Class II molar relationship when compared to the control group.

4.2. Treatment Changes Comparison

Both treated groups presented a restriction of the forward displacement of the maxilla, however with a significant difference only between JJ and control groups.

JJ group presented a smaller increase of the effective length of the maxilla during treatment when compared to the other groups. This means that the JJ promoted a greater restriction of the maxillary growth in relation to MPA and the normal growth in untreated subjects. MPA was not effective in producing a significant restriction of the forward displacement of the maxilla, since there was not a statistically significant difference with the control group.

The effect of restricting the anterior growth and displacement of the maxilla was already observed in some studies evaluating cases treated with the JJ [11, 16-23].

The lack of significant difference in the maxillary skeletal component between the groups MPA and control was already observed by other authors [8, 24].

Some studies described the decrease of SNA angle and the backward relocation of the A point with the use of JJ appliance as the “headgear effect”, with distalization and intrusion forces in the maxillary posterior region [18, 19, 22]. However, since MPA has the same mechanism of Class II correction as JJ, this effect was also expected in MPA group, but this was not observed. Therefore, the uprighting effect of both appliances on the maxillary incisors led to forward relocation of A-point because of appositional changes at that alveolar area. Since the MPA group had more palatal tipping of the maxillary incisors [9], this could have camouflaged the restrictive effect of the MPA on the maxilla. Other researchers also reported A-point relocation related to the incisor inclination [22, 25, 26].

MPA group demonstrated a significantly greater increase in mandibular effective length when compared to JJ and control groups. This corroborates other studies, however, they also found a significant mandibular protrusion [5-8, 24].

It is noticed that there was no significant mandibular protrusion neither a significant increase in mandibular effective length with the use of JJ. This is in agreement with previous studies [16, 17, 19-21, 27]. However, some authors reported mandibular protrusion with the use of the JJ [11, 23, 26, 28].

Another factor that can explain this difference, despite the similar pretreatment age of the groups, is that the MPA group presented a significantly smaller mandibular effective length in this stage than the other groups. Possibly these subjects still were at the beginning of the craniofacial growth spurt.

The two experimental groups treated with MPA and JJ showed a significant improvement of the maxillomandibular relationship when compared to the control group, also reported in the literature [8, 9, 16-18, 20-23, 26-29]. This improvement of the maxillomandibular relationship results mainly of the restriction of the forward displacement of the maxilla in the JJ group and the increase of the mandibular effective length in the MPA group and the mandibular normal growth in the JJ group.

The vertical component remained practically unchanged in all groups evaluated, indicating that treatment with MPA and JJ did not influence the craniofacial growth pattern. Some authors reported an increase of the vertical measurements, with a tendency of clockwise mandibular rotation in patients treated with the JJ appliance [16-19, 22, 26], while others did not verify significant vertical changes [20, 27].

MPA group presented a greater palatal tipping and a greater retraction of the maxillary incisors when compared to the JJ and control groups. This is probably because, at the beginning of treatment, the maxillary incisors in the MPA group were significantly more labially tipped, and consequently, during treatment, a greater retrusion was needed in order to correct the overjet. This palatal tipping corroborates some previous findings about MPA [5, 8, 24, 30].

Some studies found a significant retrusion of the maxillary incisors in cases treated with the JJ [16-19, 22, 26, 28]. The lack of significant retrusion of JJ group in the present study may be due to the greater maxillary retrusion observed during treatment [16].

MPA group presented greater labial tipping of the mandibular incisors with treatment, when compared to the control group, already mentioned in the literature [8, 24]. In JJ group, this side effect probably was minimized by the lingual crown torque applied to the mandibular anterior teeth [11, 16, 17].

JJ group presented greater protrusion of the mandibular incisors in relation to the control group, corroborating previous studies [16-19, 21-23, 26-28]. However, this significant protrusion was also reported by studies evaluating MPA [8, 24].

Both experimental groups presented significant decreases of the overjet and overbite and significant improvement in molar relationship with treatment, in relation to the control group. However, MPA group showed a greater decrease of overjet also significant when compared to JJ group.

The greater decrease of the overjet in MPA group in relation to JJ group can be explained by the pretreatment increased overjet presented by MPA group. This way, the overjet correction needed to be greater in MPA group.

The correction of overjet was several times previously reported in the literature [8, 16-24, 26, 28].

In MPA group, the overjet correction was due to the increase in mandibular effective length, the palatal tipping of the maxillary incisors and the protrusion and proclination of the mandibular incisors. In JJ group, the overjet correction was mainly due to the restriction of the forward displacement of the maxilla and the protrusion of mandibular incisors, associated with the normal mandibular growth.

The labial inclination of mandibular incisors in MPA group and the protrusion of these teeth in JJ group may have contributed to the relative “Intrusion Effect” of these teeth and correction of the overbite [20, 26, 28].

In general, MPA and JJ associated with fixed appliances corrected the Class II malocclusion, and this was due to some skeletal and mainly dentoalveolar changes [8-10, 18-22, 24, 27]. This way, both appliances can be used in growing patients as well as in adults, that do not present growth potential [9, 10, 16, 18].

However, these skeletal and dentoalveolar changes presented important differences between the two appliances, that must be remembered when planning an orthodontic treatment.

In MPA group, there was a significant increase in mandibular effective length and great dentoalveolar compensation, including palatal inclination and retrusion of the maxillary incisors and buccal inclination of mandibular incisors.

In JJ group, there was a significant restriction of the anterior displacement of the maxilla, and also important dentoalveolar compensations, as protrusion of mandibular incisors.

This way, JJ must be indicated mainly in cases with a maxillary protrusion, and MPA, especially in cases with mandibular deficiency.

Thus, the most important of the orthodontic treatment is the detailed planning and the correct determination of the treatment protocol. Further researches are needed in order to evaluate the long-term stability of treatment with MPA and JJ associated to fixed appliances.

Functional appliances can also be used in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis, to reduce the asymmetry of mandibular growth and TMJ disorder [31]. Functional appliance can reduce the pain during jaw movement, maximal mouth opening, TMJ sounds and crepitations and TMJ click [31].

CONCLUSION

The JJ group presented a greater restriction of growth and anterior displacement of the maxilla and greater maxillary retrusion and the MPA group showed a significantly greater increase of mandibular effective length. Both experimental groups showed significant improvement in maxillomandibular relationship. Maxillary incisors presented greater retrusion and palatal inclination in MPA group. Regarding mandibular incisors, the MPA group presented greater labial inclination and the JJ group showed greater protrusion. The MPA and JJ groups presented a decrease in overbite and over jet.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee in Human Research of the Bauru Dental School, University of São Paulo, Bauru, SP, Brazil.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals were used in this research. All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Written informed consent has been obtained from all patients.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.