Do Products Preventing Demineralization Around Orthodontic Brackets Affect Adhesive Bond Strength?

Abstract

Objective:

This study investigated the effects, on the shear bond strength of orthodontic brackets, of using an antimicrobial selenium-containing sealant (DenteShieldTM) to serve dual functions of priming enamel prior to bonding and as a protective barrier against whitespot lesion formation.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 150 extracted human premolars were randomly assigned into 10 groups (n=15/group). Stainless steel brackets were bonded with two adhesive systems (DenteShieldTM or Transbond XT) after the enamel was conditioned with a primer (DenteShieldTM or Assure Universal) or a filled resin sealant (DenteShieldTM, Pro SealTM or Opal SealTM). The specimens were stored in deionized water at 37 °C for 24 hours and debonded with a universal testing machine.

Results:

The use of DenteShieldTM adhesive to bond orthodontic brackets to the enamel surface resulted in a significantly lower (P<0.05), but clinically acceptable, shear bond strength (mean & SD: 14.5±1.6 MPa) as compared with Transbond XT group (mean & SD: 19.3±1.7 MPa). DenteShieldTM sealant used as primer resulted in shear bond strength values comparable to those of Pro SealTM and Opal SealTM. All adhesive-sealant and primer-sealant combinations tested in this study exhibited shear bond strength values greater than 9.6 MPa, sufficient for clinical orthodontic needs.

Conclusion:

DenteShieldTM sealant can serve as primer as well as anti-demineralization sealant during orthodontic treatment without adversely affecting the shear bond strength of the bracket.

1. INTRODUCTION

Enamel demineralization, known as White Spot Lesion (WSL), is an unwelcomed but common occurrence in patients undergoing orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances [1]. The reported prevalence of WSLs associated with fixed appliances ranges from 15% to 85% [2-4]. The higher risk for developing WSLs in orthodontically treated patients is attributed to the fixed appliances that create plaque retention sites, limit the naturally occurring self-cleansing mechanism of the oral musculature and saliva, and make proper cleaning around orthodontic brackets difficult [4, 5].

Although the majority of WSLs can re-mineralize after removal of orthodontic appliances, many of these lesions are irreversible, which can pose a cariogenic and cosmetic problem for many orthodontically treated patients [6, 7]. Numerous attempts have been made to minimize or eliminate the formation of WSLs. Vigilant oral hygiene regimen and frequent application of fluoride have been deemed the most efficient method for preventing WSLs [8, 9] However, the effectiveness of these methods is directly related to the patient’s full compliance which is unlikely, as highlighted by some studies [10-13].

To address the compliance issue, a number of methods have been proposed. One approach to minimize enamel demineralization, independent of patient compliance, is the application of resin sealants on the enamel surface around and beneath the orthodontic brackets. Light-cured sealants such as Pro SealTM and Opal SealTM have been purported to be effective in reducing the risk of WSL formation. When applied around and beneath orthodontic brackets, these sealants create a physical barrier that protects enamel against bacterial acid challenge without adversely affecting the bond strength of orthodontic brackets [14]. These sealants are highly filled, and thus their wear resistance are superior to that of unfilled resins [15].

Several in vitro studies demonstrated a reduction in enamel demineralization associated with bonded orthodontic brackets when a fluoride-releasing sealant was used [15-17]. Yet, Leizer et al., [18] and Tufekci et al., [19] found no clinically significant differences in the effectiveness of these sealants and control groups. The ability of fluoride-releasing sealants to minimize the occurrence of WSLs depends on the amount of fluoride released into the adjacent environment and more importantly on their continued ability to release fluoride ions over time [20]. Previous studies have shown that the rate of fluoride ions released from these sealants decrease sharply over the first few weeks after application [21]. Therefore, despite having an initial positive protective effect, the efficacy of these fluoride-releasing sealants in the long term is uncertain.

DenteShield TM (SelenBio Inc, Austin, TX, USA) (DS) is a recently introduced light-cured antibacterial sealant that has been developed to combat WSLs during orthodontic treatment. It contains selenium which in polymer form can produce superoxide radicals [22], causing oxidative stress that damages the bacterial cell wall and DNA [23, 24]. In an in vitro investigation, Tran et al., [25] demonstrated the ability of DS sealant to inhibit bacterial attachment and biofilm formation by two of the main culprits in plaque development, namely Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus salivarius. These bacteria cannot survive under selenium-containing sealant as opposed to regular dental sealants [25]. Furthermore, selenium-containing sealants such as DS, when polymerized, do not leach selenium and are thus believed to sustain their antibacterial effects over time. Selenium forms a covalent attachment to the polymer of the sealant which prevents it from getting released into the surrounding environment [25].

Bonding orthodontic bracket to the tooth surface involves the application of a primer following etching, before sitting the bracket with an adhesive. In a situation where DS sealant is to be used to prevent WSL formation, it is advised that the sealant can as well be used as the primer to be painted on the entire tooth surface following etching. This procedure eliminates the multiple steps of first bonding the bracket using primer and adhesive, and then painting sealant on the remaining tooth surface. However, the effect of selenium-containing sealants on the shear bond strength of orthodontic brackets, when serving the dual functions of primer and anti-WSL, has not been extensively investigated. The only published study found that DS adhesive produced lower but clinically acceptable shear bond strengths than a conventional orthodontic adhesive [26]. Therefore, the primary purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of using a selenium-containing sealant as primer on the resulting shear bond strength of the orthodontic brackets. The study also investigated the bonding efficacy of a selenium-containing adhesive.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Teeth Preparation and Group Allocation

Following the approval of the Institutional Review Board (IRB Approval: HSC20080233N) of the University of Texas Health at San Antonio (UT Health), freshly extracted unidentified human molar teeth appropriately disposed in various clinics of the UT Health School of Dentistry, were collected, examined and stored in 0.1% thymol solution. One hundred fifty molars that met the inclusion criteria of intact buccal enamel, with no cracks, no caries, and no enamel malformation were selected. The teeth were cleaned with a rubber prophylactic cup and oil-free pumice slurry for 10 seconds to remove the remnants of pellicle, debris, and stains. They were then rinsed thoroughly and individually mounted in cylindrical polycarbonate mounting rings using cold-curing acrylic resin. A mounting jig was used to mount the teeth in the same repeatable position, i.e. to mount the teeth in such manner that their buccal surfaces would be parallel to the applied force during the shear test. Tooth specimens were kept moist throughout the study to prevent desiccation. The 150 tooth specimens were randomly assigned to 1 of 10 groups (15 teeth per group). There were 4 primer-adhesive and 6 sealant-adhesive groups. The primer-adhesive groups were Assure/Transbond XT, Assure/DS adhesive, DS primer/Transbond XT, and DS primer/adhesive. The sealant-adhesive groups were DS sealant/Transbond XT, DS sealant/ DS adhesive, Pro Seal/Transbond XT, Pro Seal/ DS adhesive, Opal Seal/Transbond XT, Opal Seal/ DS adhesive. The materials used are listed in Table 1 . The instructions of use from the 4 manufacturers were closely followed when bonding the brackets to the teeth. One hundred fifty identical stainless steel maxillary first premolar brackets (Victory Series™, 3M Unitek, Monrovia, CA, USA) were used in this study to ensure consistency.

| - | Material Name | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|

| Adhesive | Transbond XT | 3M Unitek, Monrovia, CA, USA |

| DenteShieldTM | SelenBio Inc, Austin, TX, USA | |

| Primer | Assure Universal | Reliance Orthodontic Products, Itasca, IL, USA |

| DenteShieldTM Primer | SelenBio Inc, Austin, TX, USA | |

| Sealant | DenteShieldTM Sealant | SelenBio Inc, Austin, TX, USA |

| Pro Seal™ | Reliance Orthodontic Products, Itasca, IL, USA | |

| Opal Seal™ | Ultradent Products, South Jordan, UT, USA |

2.2. Bracket Bonding

For each group, the teeth were dried thoroughly by air, acid etched with 37% phosphoric acid gel for 30 seconds, rinsed with oil-free air/water spray for 15 seconds, and dried until the enamel surface of the etched teeth appeared to be chalky white. A thin, uniform coat of the primer or sealant (Table 1) was then painted on the etched surface using a brush. Subsequently, adhesive was applied to the bracket pad and the bracket seated firmly onto the buccal surface with bracket placement forceps. After removing excess adhesive with a small scaler, each bracket was light cured at close range for 12 seconds according to the manufacturers’ instructions. The curing light, Ortholux™ Luminous Curing Light (3M Unitek, Monrovia, CA, USA), was a high intensity LED with an output of at least 1600 mW/cm2. All specimens were stored in deionized water and incubated at 37ºC for 24 hours before shear bond strength testing.

2.3. Shear Bond Strength Testing

Twenty four hours after bonding, the rings were secured in a shear bond testing fixture. Using a calibrated universal testing device (model 5565, Instron, Norwood, MA, USA), a load parallel to the bracket base in a gingival direction was applied to each bracket, producing a shear force at the bracket-tooth interface at a crosshead speed of 1.0 mm per minute. The load applied at the point of bond failure was recorded in Newtons (N) by the computer software, and the shear bond strengths were measured and recorded in Megapascals (MPa), where MPa = N/bracket base surface area. The surface area of the bracket base was 12.25 mm2.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The sample size calculation for this study was performed using nQuery Advisor software (Statistical Solutions, Cork, Ireland) and was based on historical data from a previous study [ 23 ]. It was estimated that approximately 15 samples should be included in each experimental group to detect a difference of approximately 2.0 MPa between groups. Calculations were based on standard deviations recorded historically in similar studies [ 14, 23, 26, 27] with an α of 0.05 and statistical power of 80%. Statistical analysis of the data was performed with SPSS (version 14.0, Chicago IL, USA) with the level of significance (α) pre-chosen at 0.05. Descriptive statistics, including the mean, standard deviation, and minimum and maximum values, were calculated for each of the groups tested. Bonferroni protected Mann-Whitney tests were used to conduct intra- and inter-group comparison of the shear bond strengths. Further inter- and intra-group comparisons of the shear bond strength was carried out using 2-way factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA).

3. RESULTS

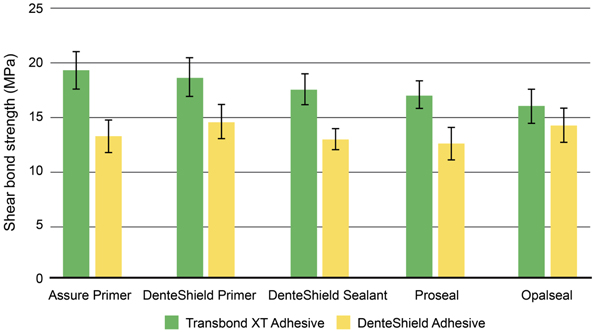

The mean shear bond strengths, standard deviations, and ranges for each primer-adhesive and sealant-adhesive combination tested are summarized in Fig. (1) and Table 2 . Data were analyzed by 2-way factorial analysis of variance. One factor represents type of sealant with five levels, and the other factor represents type of adhesive with 2 levels. In the omnibus analysis all effects were statistically significant at the P < 0.05 level [main effect of sealant: F(4, 140) = 8.23, p < 0 .001; main effect of adhesive: F(1, 140) = 289.48, P < 0.001; sealant by adhesive interaction: F(4, 140) = 8.06, P < 0.001]. The sealant by adhesive interaction was further explored by analyzing the simple main effect of adhesive at each level of sealant. This analysis showed that for all sealants, except Opal Seal, the bond strength of Transbond XT is significantly stronger (P < 0.05) than that of DS adhesive.

| Group | Sealant /Primer | Adhesive | Mean† | SD | Range* | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combination 1 | Assure Universal primer | Transbond XT | 19.3 | 1.7 | 16.9 - 21.7 | 15 |

| Combination 2 | Assure Universal primer | DenteShieldTM | 13.2 | 1.5 | 11.1 - 16 | 15 |

| Combination 3 | DenteShieldTM Primer | Transbond XT | 18.6 | 1.8 | 15.7 - 22.9 | 15 |

| Combination 4 | DenteShieldTM Primer | DenteShieldTM | 14.5 | 1.6 | 11.9 - 17.2 | 15 |

| Combination 5 | DenteShieldTM Sealant | Transbond XT | 17.5 | 1.4 | 15.5 - 19.6 | 15 |

| Combination 6 | DenteShieldTM Sealant | DenteShieldTM | 12.9 | 1 | 11.5 - 14.6 | 15 |

| Combination 7 | ProSeal sealant | Transbond XT | 17 | 1.3 | 15.2 - 19.3 | 15 |

| Combination 8 | ProSeal sealant | DenteShieldTM | 12.5 | 1.5 | 9.6 - 16.2 | 15 |

| Combination 9 | OpalSeal sealant | Transbond XT | 16 | 1.5 | 13.6 - 18.2 | 15 |

| Combination 10 | OpalSeal sealant | DenteShieldTM | 14.2 | 1.6 | 11.8 - 17.7 | 15 |

Simple main effect analysis indicated that Transbond XT/ Assure primer (mean 19.3 ± 1.7 MPa) and Transbond XT/ DS primer (mean 18.6 ± 1.8 MPa) had similar shear bond strength values. Similar trend was observed when either primer was applied with DS adhesive. No significant difference in shear bond strength was found between DS primer and DS sealant when used with either DS adhesive or Transbond XT. No significant differences in shear bond strength detected among the three different sealants tested, Pro Seal, Opal Seal, and DS (P > 0.05), when used with either of the tested adhesives. However, the bond strength was numerically higher but not statistically significant, when primer (either Assure or DS) was used with Transbond XT compared to using any of the sealants. This phenomenon was also observed with DS adhesive.

4. DISCUSSION

The objective of the present study was two-fold. The first was to investigate the possibility of the DS protective sealant serving as a primer without jeopardizing the bond strength of orthodontic brackets. To this end, the effect on the shear bond strength of adhesive systems when the selenium-containing sealant was first applied to the surface of the tooth was determined and compared to that of DS primer and other commercially available sealants and primers. The second objective was to evaluate the bonding efficacy of the DS adhesive which was tested against Transbond XT, which is a very commonly used orthodontic bonding adhesive.

The shear bond strength of DS adhesive was significantly lower than that of Transbond XT, regardless of the type of sealant or primer used (except for Opal Seal). However, the bond strength remained well above the clinically acceptable level. These results, which are in agreement with those reported by Machicek et al., [26], suggest that adequate bond strengths can be achieved with this selenium-containing adhesive system.

Although Transbond XT produced significantly higher shear bond strength than DS adhesive, from a clinical perspective, it is important to obtain adequate bond strength that allows for safe debonding than to obtain the greatest possible bond strength. High shear bond strength may very well pose a clinical problem during debonding, which may involve enamel crack or fracture.

All sealant-adhesive and primer-adhesive combinations tested in this study had shear bond strength above 9.6 MPa which exceeds the minimal range recommended for routine clinical use (6 - 8 MPa) [27]. The variability observed in mean shear bond strength values for each adhesive combined with different sealants might be attributed to the compatibility between the adhesive and the sealants.

Our findings indicated that for each adhesive system tested in this study, using a filled resin sealant as opposed to an unfilled resin primer prior to adhesive lowered bond strength values to a non-significant extent. Lowder et al14 also reported similar observation. However, the fact that a clinically acceptable bond level was achieved regardless of whether a primer or a sealant used for priming, indicates that any of the tested sealants can be used alone for priming enamel during orthodontic bonding while sealing the tooth surfaces. Therefore, using protective sealants is thought to simplify the orthodontic bonding procedure by condensing the priming and sealing steps in one application. It is pertinent to mention that this report being an in vitro investigation also has the general limitations of this kind of studies; the tested agents were not subjected to the biological and physiological factors and activities that occurs in oral environment, which would inevitably affect the shear bond strength under in vivo conditions. Thus, the result of the present study may not mirror what would be obtained in vivo with regards to the shear bond strength.

In comparison to sealants such as Pro Seal and Opal Seal that only creates physical barrier to acid demineralization, DS sealant has the advantage of creating not only a physical barrier but also a biological barrier against caries-causing oral bacteria [25] and yet providing comparable bond strength for orthodontic bonding. In the present study, DS adhesive system shows promise as an effective and reliable method for orthodontic bonding. Further investigation is needed to determine if antibacterial effects of DS adhesive system are clinically translated into reduced WSL formation during orthodontic treatment. Future research should also attempt to determine the site of bond failure and assess the adhesive remnants on the bracket after bracket debonding.

CONCLUSION

The following conclusions can be drawn from this in vitro study:

- DS sealant did not adversely influence the bond strength of orthodontic brackets.

- DS adhesive can provide sufficient bond strength necessary for orthodontic treatment.

- The resulting shear bond strength of DS sealant is comparable to that of the commonly used fluoride-releasing sealants.

- All primer-adhesive and sealant-adhesive combinations studied demonstrated clinically acceptable shear bond strength values above 9.6 MPa.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| ANOVA | = Analysis of Variance |

| DS | = DenteShieldTM |

| MPa | = Megapascals |

| N | = Newtons |

| WSL | = White Spot Lesion |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The collection of extracted unidentified human teeth used in the present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB Approval: HSC20080233N) of the University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals/humans were used for studies that are the basis of this research.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none