All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Career Motivations, Perceptions of the Future of Dentistry and Preferred Dental Specialties Among Saudi Dental Students

Abstract

Aim:

The purpose of this study was to determine the career motivations, perceptions of the future of dentistry and preferred postgraduate specialties of Saudi dental students.

Methods:

A pretested, self-administered, 16-item questionnaire was distributed to first- through fifth-year dental students at King Saud University in Saudi Arabia. Descriptive statistics were calculated, and the level of significance was set at 5%.

Results:

Of the 530 potential participants, 329 students (198 male and 131 female respondents) completed the questionnaire. High professional status (71.4%), a secure career (67.8%), a high income (78.1%), flexible working hours (54.4%), a wide range of career options after graduation (59.3%), opportunities for self-employment (69.3%) and good job opportunities abroad (65.3%) were endorsed to a great/considerable extent by the respondents. “It takes time to establish a practice” (62.3%), “Postgraduate education is a necessity” (72.4%) and “The increasing number of dental institutions is a threat to the profession” (59.3%) were endorsed to a great or considerable extent by the respondents. The most popular specialty among the male students was oral maxillofacial surgery (20.1%) and among female students was operative dentistry (23.4%).

Conclusion:

The career motivations of this group of dental students seemed to relate to socioeconomic aspects of dentistry and perceptions of the future of dentistry seemed to relate to the need for postgraduate education.

INTRODUCTION

As licensed healthcare workers, dentists occupy an important position in society [1]. There have been several studies by dental educators and researchers concerning the motives for entering the dental profession. The motivating factors for selecting any career are complex, and dentistry is no exception. Many issues may be considered when choosing a career, including one’s own strengths and weaknesses, interests and desires and willingness and financial ability to complete a possibly lengthy period of training as well as the type of work involved in a particular career, work environment, financial rewards and availability and attractiveness of alternative careers. Moreover, the relative importance of these factors may differ between men and women [2].

In particular, it is essential to understand the motivating factors, priorities, perceptions of the profession and sociodemographic backgrounds of students who choose to study dentistry [3]. Many individuals find themselves in occupations without truly understanding the reasons for their attraction to their career. Others make career decisions and pursue an occupation supported by their parents or follow in the footsteps of an older sibling [4]. High social status and income, helping people [1, 5] and self-employment opportunities [2, 5] are some of the most important factors reported to have influenced dental students’ motivation to pursue a career in dentistry. The choice of career is a critical decision with a strong influence on one’s future. Research into the motivations and expectations of dental students is especially important due to the duration and cost of training [6].

In 1987, Saudi Arabia had 3 dental schools, and the total number of dentists was 786; the dentist-to-population ratio was 1:8,906 [7]. According to 2012 Ministry of Health statistics, there are currently 10,011 dentists in Saudi Arabia, and the dentist-to-population ratio is 1:2,857 [8]. Furthermore, there are now 22 dental schools (7 private and 15 public), and a total of 3,324 students (2,250 men and 1,074 women) were enrolled in all years of study in the 15 public dental colleges in 2012 [9]. The College of Dentistry at King Saud University was established in 1975 in Riyadh as the first university-based public dental institution in Saudi Arabia [10]; it offers a six-year dentistry program that includes a one-year internship. The college is currently recognized by the Association of Dental Education in Europe (ADEE) and accredited by the National Commission for Academic Accreditation and Assessment (NCAAA). The students admitted to King Saud University participate in a one-year preparatory course after which, based on their grade point average (GPA), they are admitted to a medical, dental or other allied college.

Although other Saudi Arabian studies have reported the levels of interest in different postgraduate specialties and the career choices of graduate dentists [10, 11], none have explored the career motivations and interests in postgraduate specialties among students currently enrolled in dental school. Furthermore, no studies have investigated the future of dentistry as perceived by dental students. Consequently, this study was designed to elicit the career motivations, attitudes toward the future of dentistry and levels of interest in various postgraduate specialties among Saudi dental students at the College of Dentistry at King Saud University and to explore the differences in these aspects by gender.

MATERIALS AND METHODOLOGY

The subjects of this study were students enrolled in the College of Dentistry at King Saud University, and the study was approved by the College of Dentistry Research Center (CDRC; registration number NF2314). At the time of this study, a total of 571 students (373 men and 198 women) were enrolled in the dentistry program. The questionnaire was designed to maximize the response rate and minimize missing data; hence, it was as brief as reasonably possible. The 16-item questionnaire was pretested with a group of 5 randomly selected male and female students who were each in their first- or fifth-year to identify any obstacles to its comprehension, and necessary modifications were made accordingly. These students were not included in the final analysis.

During the 2011-12 academic year, first-year through fifth-year students were invited to voluntarily participate in our questionnaire survey. At the end of a regularly scheduled classroom lecture, the questionnaires were distributed to a total of 530 students present on the day of the survey by their respective class representatives to be completed and returned immediately. An introductory first page explaining the purpose of the study and assuring the confidentiality of the participants’ information was attached to the questionnaire. The vocational and socioeconomic factors reported by Vigild and Schwarz [1] and the flexibility and business factors reported by Scarbecz and Ross [2] are characteristics that distinguish dentistry from many other professions; these factors may be considered important from a student’s perspective. Consequently, seven statements were derived based on the motivation factors from the above-mentioned studies [1, 2]. The questionnaire included the following career motivations: a) high professional status; b) a secure career; c) a high income; d) flexible working hours; e) a wide range of career options after graduation; f) opportunities for self-employment; and g) good job opportunities abroad. Furthermore, the questionnaire included the following three statements related to the students’ attitudes and perceptions of the future of dentistry: a) “It takes time to establish a practice,” b) “Postgraduate education is a necessity,” and c) “The increasing number of dental institutions is a threat to the profession.” The students were asked to indicate their level of agreement with each of seven statements regarding the influences on their choice of dentistry and each of three statements concerning their attitudes and perceptions of the future of dentistry using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from “not at all” to “to a great extent.”

Demographic information, including age, gender and year of study, was obtained. The students were also asked whether one or both of their parents were dentists. The students were asked to identify the person with the greatest influence on their choice to pursue a career in dentistry (parents/family, a friend, self, a family dentist, a teacher or a counselor) and their primary field of interest before applying dental school (dentistry, medicine, pharmacy, engineering or other) by responding to close-ended questions.

All of the completed questionnaires were collected for data analysis, which was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 16.0 software for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics (i.e., frequency distributions) were calculated. For all of the analyses, a p-value of 0.05 was considered the threshold for statistical significance.

RESULTS

Of the 530 potential participants, 329 students (198 male and 131 female respondents) completed the questionnaire. Among the men, the response rates according to the year of study were first-year (63.4%), second-year (55.1%), third-year (64.5%), fourth-year (71.6%) and fifth-year (28.3%) with an overall response rate of 56.6%. Among the women, the response rates according to the year of study were first-year (73.2%), second-year (43.2%), third-year (83.7%), fourth-year (52.6%) and fifth-year (93.5%) with an overall response rate of 69.2%. The mean age of the male students was 21 ± 1.5 years, and the mean age of the female students was 20.9 ± 1.2 years. The demographic characteristics of the study population based on gender are shown in Table 1.

Demographic variables of dental students by gender.

| Demographic Variables | Males n=198 (%) |

Females n=131 (%) |

Total N=329 N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year of study | |||

| 1st | 63.4 | 36.6 | 82 (24.9) |

| 2nd | 70.4 | 29.6 | 54 (16.4) |

| 3rd | 52.6 | 47.4 | 76 (23.1) |

| 4th | 72.6 | 27.4 | 73 (22.2) |

| 5th | 34.1 | 65.9 | 44 (13.4) |

| One or both parents dentists¹ | |||

| Yes | 65 | 35 | 20 (6.1) |

| No | 59.9 | 40.1 | 307 (93.9) |

1 Missing values=2

The individuals with the greatest influence on the choice to pursue dentistry and the primary field of interest according to gender.

| Males n=198 (%) |

Females n=131 (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Influential person | 0.042* | ||

| Parents/family | 32.7 | 46.5 | |

| Friends | 9.2 | 3.1 | |

| Self | 45.9 | 41.9 | |

| Family dentist | 9.2 | 5.4 | |

| Teacher/counselor | 3.1 | 3.1 | |

| Primary field of interest | 0.023* | ||

| Dentistry | 64.6 | 54.2 | |

| Medicine | 28.3 | 32.8 | |

| Pharmacy | 0 | 4.6 | |

| Engineering | 2.0 | 3.1 | |

| Other | 5.1 | 5.3 | |

* Statistically significant

The level of agreement (among all of the participants) with statements about motivating factors and the future of dentistry.

| Not at all (%) |

Small Extent (%) |

Moderate Extent (%) |

Considerable Extent (%) |

Great Extent (%) |

Missing (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motivating factors¹ | ||||||

| High professional status | 0.6 | 5.8 | 20.7 | 23.1 | 48.3 | 1.5 |

| Secure career | 2.4 | 7.6 | 21.9 | 30.7 | 37.1 | 0.3 |

| High income | 2.4 | 3.6 | 15.5 | 37.4 | 40.7 | 0.3 |

| Flexible working hours | 8.5 | 12.8 | 23.1 | 33.7 | 20.7 | 1.2 |

| Wide range of career options after graduation | 3.6 | 9.7 | 27.1 | 35.3 | 24.0 | 0.3 |

| Opportunity for self-employment | 2.4 | 6.1 | 21.3 | 35.3 | 34.0 | 0.9 |

| Good job opportunities abroad | 2.7 | 6.7 | 23.7 | 31.9 | 33.4 | 1.5 |

| Perceived future of dentistry² | ||||||

| It takes time to establish a practice. | 1.5 | 8.8 | 25.5 | 29.5 | 32.8 | 1.8 |

| Post-graduate education is a necessity. | 2.1 | 7.3 | 17.3 | 35.9 | 36.5 | 0.9 |

| The increasing number of dental institutions is a threat to the profession. | 8.5 | 8.2 | 22.5 | 37.1 | 22.2 | 1.5 |

1Cronbach’s alpha=0.85; 2Cronbach’s alpha=0.63

The individuals with the greatest influence on the choice to pursue dentistry and the primary fields of interest reported by the students are shown according to gender in Table 2. Approximately 46% of the male respondents pursued dentistry based on their own interest, whereas 46.5% of the female respondents reported that their parents/family influenced their choice of dentistry as a profession. Dentistry was the primary field of interest for the majority of both the male (64.6%) and female (54.2%) students. However, medicine had been the first preference for 28.3% of the male students and 32.8% of the female students.

The percentages of respondents reporting their various levels of agreement with the statements related to the choice of dentistry as a career and the perceived future of dentistry are shown in Table 3. High professional status (71.4%), a secure career (67.8%), a high income (78.1%), flexible working hours (54.4%), a wide range of career options after graduation (59.3%), opportunities for self-employment (69.3%) and good job opportunities abroad (65.3%) were endorsed to a great/considerable extent by the respondents. Approximately 64% of the female respondents agreed to a great extent with the item “high professional status” compared with approximately 39% of male respondents. The only significant difference between the genders was in the response to this item (p<0.001).

“It takes time to establish a practice” (62.3%), “Postgraduate education is a necessity” (72.4%) and “The increasing number of dental institutions is a threat to the profession” (59.3%) were endorsed to a great or considerable extent by the respondents. There were significant differences between the men and women concerning their agreement with the following statements: “It takes time to establish a practice” (p=0.001) and “Postgraduate education is a necessity” (p<0.001). A higher percentage of female students (39.4%) agreed to a great extent with the item “It takes time to establish a practice” compared with male students (29.6%). A higher percentage of female students (52.7%) also agreed to a great extent with the item “Postgraduate education is a necessity” compared with male students (26.4%). However, there were no gender-related significant differences concerning their agreement with the statement “The increasing number of dental institutions is a threat to the profession” (p=0.053). The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients for the scales used to assess the motivating factors and perceptions of the future of dentistry were 0.85 and 0.63, respectively.

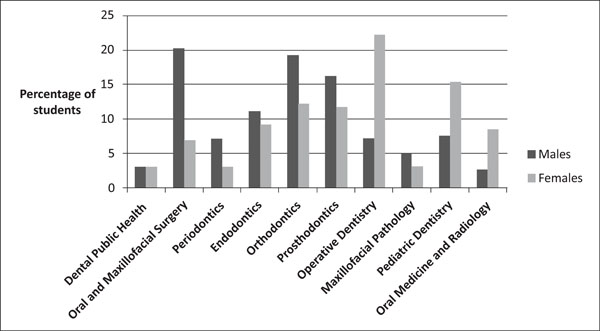

The number of participants reporting an interest in various specialties is shown according to gender in Fig. (1). There were gender-related significant differences concerning preferred specialties (p<0.001). The most strongly preferred specialty among the male students was oral and maxillofacial surgery (20.4%), and the most strongly preferred specialty among the female students was operative dentistry (23.4%).

Participants’ specialties of interest by gender (percentage).

DISCUSSION

This report describes the career motivations, attitudes toward the future of dentistry and levels of interest in various specialties among dental students. The results of this survey showed that more than 54% and 59% of the respondents agreed to a considerable or great extent with all of the statements concerning their career choice and the future of dentistry, respectively. For approximately 20% of male students, the preferred specialty of interest was oral and maxillofacial surgery, whereas operative dentistry was the most preferred specialty for approximately 23% of female students. The results presented here are the first to be reported for Saudi dental students.

Approximately 6% of the participants in this study had at least one parent who was a dentist. A study that compared Japan and Sweden revealed that nearly 60% of Japanese dental students had at least one parent who was a dentist [12]. An Iranian study reported that dental students with at least one parent practicing dentistry scored significantly lower on the “characteristics of the profession” dimension than other students, and the authors attributed this result to a greater degree of familiarity with the difficulties of practicing dentistry among students with a parent in the dental profession [13]. Several other studies have reported that having friends and relatives in the dental profession was an important factor in their subjects’ career choices [14, 15]. Because of the low percentage (6.1%) of respondents in this study who had at least one parent in dentistry, the influence of having a dentist as a parent on the respondents’ career choices should be interpreted with caution.

Most Saudi students live with their families; thus, their parents may play a major role in their career decisions. Parents/family was the most influential factor in the decision to pursue a career in dentistry for approximately 38% of all the participants, including 33% of males and 46% of females. These numbers are comparable to other studies that have reported a strong parental influence on the career decisions of their respondents [16-18]. However, the majority of male students (approximately 46%) chose dentistry based on their own interest, which is consistent with the results of a Turkish study that found that approximately 72% of male respondents reported that pursuing dentistry was a personal decision [19].

Some studies have found that dentistry was the first career choice for the majority of dental students [15, 20], whereas other studies have reported that medicine was their first preference [5, 21]. In this study, dentistry was the primary field of interest for the majority of both the male and female students. However, approximately 28% of male and 33% of female students reported that medicine was their primary field of interest. These results are similar to the results of a Turkish study that revealed that dentistry was the first choice of the majority of the students and that among the students whose first choice was not dentistry, the majority had selected medicine as their initial preference for higher education [19]. A Nigerian study [22] reported that 60% of the respondents had selected medicine as their first choice; half of the respondents had unsuccessfully attempted to change their course of study, and a few wished to change it. Some students continue their studies in dental schools although their original primary field of interest was not dentistry. This fact may have far-reaching implications because these students may be compelled to pursue a profession that may not fulfill their career expectations. Additional longitudinal studies evaluating the differences in academic performance or graduation rates between students whose primary field of interest was dentistry or other fields may offer a broader view of the implications of making the wrong career choice. Future studies should also assess whether the students whose first preference was medicine or another profession have attempted to change their course or would wish to do so in the future.

Some surveys of dental students have revealed that professional status, financial rewards, security and stable work are the major factors involved in choosing dentistry as a profession [5, 20, 23]. The majority of the respondents in this study agreed to a considerable or great extent with the vocational, socioeconomic, flexibility and business factors stated in the questionnaire as motivating factors for pursuing a career in dentistry, which is in line with the results of previous studies [16,18-20]. In this study, a relatively higher percentage of respondents agreed to a considerable or great extent with “high income” and “high professional status” compared with other motivating factors; this reflects the influence of monetary and social factors on the minds of majority of the students. A study evaluating first-year dental students’ motivations for attending dental school demonstrated that the relative importance of factors influencing students to choose dentistry may differ between the genders [2]. The results of this study showed that more women than men endorsed “high professional status” as a motivation.

Three items (the time required to establish a practice, the need for postgraduate education and the increasing number of dental institutions as a threat to the profession) were included in the questionnaire to evaluate the students’ perceptions of the future of dentistry. The majority of the respondents endorsed the three statements to a considerable or great extent. A relatively higher percentage of respondents agreed to a considerable or great extent with “Postgraduate education is a necessity” compared with the other two factors concerning the students’ perception of the future of dentistry. More women than men agreed that “It takes time to establish a practice” and that “Postgraduate education is a necessity.” A recent Saudi study reported that a relatively low proportion of female dentists had obtained postgraduate education leading to either a clinical specialty or an academic degree; this result was attributed to the impact of family commitments and responsibilities, which may have overcome the motivation to pursue postgraduate education [11]. However, the majority of the female respondents in this study recognized that postgraduate education is necessary for career advancement. A study conducted by Aggarwal et al. [16] explored the attitudes of dental students toward the future of dentistry in India; however, these attitudes were not assessed and reported in detail. Thus, the results of this study on other issues (i.e., “It takes time to establish a practice” and “The increasing number of dental institutions is a threat to the profession”) cannot be compared to other studies.

The Indian study reported a decrease in the number of students admitted to dental schools, and the authors attributed this decrease to a rapid increase in the number of dentists in India, which may have discouraged some prospective students who would have considered that the increased competition would limit their future earnings [16]. There has been an increase in the number of dental schools in Saudi Arabia from 1975 [7] to 2012 [9], and the dentist-to-population ratio has increased from 1:8,906 [7] in 1987 to 1:2,857 in 2012 [8], which has surpassed the projected ratio of 1:2,500 by 2020 [7]. A larger number of dental schools will produce a larger number of graduating dentists each year, and these qualified graduates may decide to pursue the postgraduate specialty of their choice, to work in public (government-run) or private dental facilities or to enter private practice depending on their academic and clinical achievements, financial resources and career interests. The graduate-to-postgraduate dentist ratio will be affected by the relative proportions of students who choose to remain as graduate dentists or continue with postgraduate work. Because the number of postgraduate positions available in each specialty is limited, an increase in the number of graduate-level general dentists may lead to an unbalanced graduate-to-postgraduate dentist ratio. Graduates who had wished to pursue postgraduate studies but chose not to base their decision on the limited number of postgraduate positions may decide to work in public or private dental facilities or to establish private practices. Because the employment opportunities in public and private dental facilities are limited, establishing a private practice may be the only choice for some graduates.

A study conducted by Al-Hussyeen [24] reported that the level of satisfaction of the surveyed Saudi adolescents with their chosen dental clinics increased significantly with their perception of receiving high-quality dental care and visiting modern-equipped dental clinics. The general population will become increasingly aware of the various dental specialties and their regular advancements; therefore, more patients may decide to visit highly qualified and experienced dentists at well-established, state-of-the-art clinics. Thus, it may be assumed that the increased number of dental schools, the need for postgraduate education and the time required to establish a practice are interrelated factors that dental students, as future dentists, may perceive as setbacks in the future of dentistry as a profession.

The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients were 0.85 and 0.63 for the scales used to assess the motivating factors and the perceived future of dentistry, respectively. Gliem and Gliem [25] state that it is important to calculate and report Cronbach’s alpha for Likert-type scales to demonstrate the reliability of study’s measurements. The Cronbach’s alpha value for motivating factors in this study was comparable to the value in a study conducted by Scarbecz and Ross [2], although fifteen items were used to measure the four motivating factors in that study.

The majority of male respondents in this study preferred oral and maxillofacial surgery, followed by orthodontics, as their postgraduate specialties of interest, which is partially in accordance with the results of a previous Saudi study in which the majority of male dentists preferred the specialties of prosthodontics and orthodontics [10]. Furthermore, the majority of female subjects preferred operative dentistry, followed by pediatric dentistry, which is in contrast to a previous Saudi study reporting that the majority of female dentists preferred orthodontics, followed by endodontics [11]. None of the postgraduate preferences of the male and female students concurred with the results of a cross-cultural study that reported that orthodontics was the first preference of Canadian and Japanese students [17].

The majority of the students enrolled in the College of Dentistry at King Saud University were male (373 out of 571), which is in contrast to the Western world [1, 26] where a greater number of women are reported to have enrolled in dental schools. Rising numbers of female dental students have also been reported in a Nigerian study [3], a recent Turkish study [19] and an Indian study [16]. Furthermore, the results of this study conflict with the predictions of a previous Saudi study that an increasing number of women would enter the profession [27].

Some of the limitations of this study should be considered when interpreting the results. The students at private dental schools were not included in this study to evaluate any differences in perception between students of public and private dental schools. The study’s sample population was relatively small compared to the total number of dental students in Saudi Arabia. However, the sample size was comparable to both an Irish study [5] and a recent Turkish study [19]. The demographic characteristics of our respondents were comparable to the Saudi dental student population, which suggests that our results may be applicable to students at other dental schools in Saudi Arabia. Our results were derived from self-reported data and thus may have limited generalizability. The reliability of the scale used to measure the perceived future of dentistry was relatively low (Cronbach’s alpha=0.63). Future questionnaires with larger numbers of validated questions or statements addressing this issue may produce higher reliability coefficients. The response to the motivating factors, perceptions on the future of dentistry and interest in specialties may vary according to the year of study by the dental students. However, this topic was not analyzed in this study.

CONCLUSION

Within the limitations of this study, it can be concluded that the career motivations of this group of Saudi dental students seemed to be associated with the socioeconomic aspects of dentistry whereas, the perceptions regarding the future of dentistry seemed to be associated with the need for postgraduate education. To date, researchers have not examined the perceptions of dental students about the future of their profession. The relatively high percentage of respondents who endorsed the three statements about the future of dentistry indicated that these students recognized the importance of this issue. Additional cross-cultural studies, both cross-sectional and longitudinal, using validated questionnaires will provide us with a broader perspective on this issue. A large number of the students surveyed would like to pursue postgraduate studies in oral and maxillofacial surgery and operative dentistry, as these were the most popular specialties among male and female students, respectively.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author confirms that this article content has no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to thank the following groups and individuals for their valuable contributions: the College of Dentistry Research Center at King Saud University, Saudi Arabia for supporting this study (Research project # NF 2314); Dr. Salim AlMalik, General Director and Minister’s Advisor, International Affairs, Ministry of Higher Education, Saudi Arabia; Dr. Nimmi Biju Abraham and Dr. Vimal Jacob, Dental Caries Research Chair; Mr. Nassr Al-Maflehi, Biostatistician, Department of Periodontics, College of Dentistry, King Saud University. I also wish to thank the students for their participation.