All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Utilization of Oral Health Services by Pregnant Women Attending Primary Healthcare Centers in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

Introduction

Poor oral health in women is significantly associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. This study examined the utilization of oral health services by pregnant women attending primary healthcare centers (PHCs) in Saudi Arabia.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, we used an online survey to assess the utilization of dental services by pregnant women who attended prenatal care between 2018 and 2019. We examined factors that affect women’s utilization of dental care during pregnancy. Bivariate and multivariate analyses included a dental visit before pregnancy, a prenatal health provider’s advice to visit a dentist, a regular medical checkup before pregnancy, dental problems, chronic illnesses, oral health knowledge, and sociodemographic characteristics. The Type-I error rate was set at 5%.

Results

Our sample included 1350 respondents. The percentages of women who reported a dental visit before, during, and after pregnancy were 38.1%, 31.0% and 51.3%, respectively. Women who visited a dentist before pregnancy and those who were advised by a prenatal health provider to visit a dentist were more likely to report a dental visit during pregnancy (Odds Ratio [OR]=3.00; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.33-3.86; OR=2.79; 95% CI, 2.04-3.82, respectively). Women with dental problems (OR=2.68; 95% CI, 1.82-3.96) and better oral health knowledge (OR=1.16; 95% CI, 1.05-1.29) had higher odds of visiting a dentist during pregnancy.

Discussion

A significant underutilization of dental services during pregnancy was reported, with only 31% of women reporting dental visits during this period. Most pregnant women sought dental care only when in absolute need, with preventive care often being postponed until after pregnancy. Factors contributing to this underutilization included scheduling difficulties, misconceptions about dental safety, financial barriers, and dentists’ reluctance to treat pregnant women due to a lack of training or fear of litigation. These findings align with both national and international studies, suggesting universal barriers despite cultural differences. Notably, the advice of prenatal health providers significantly increased dental visits during pregnancy, highlighting the importance of integrating oral health counseling into antenatal care. Improving education for dental professionals, ensuring coordinated care, and embedding oral health screenings into prenatal visits are recommended strategies. While our large sample size strengthens these findings, the cross-sectional design limits causal inferences. Nonetheless, our study provides critical insights for policymakers aiming to integrate dental services effectively into prenatal care in Saudi Arabia.

Conclusion

Our findings highlighted that pregnant women mostly sought dental services when they were in absolute need of them. Further examination of the factors that prevent them from seeking dental care during this sensitive yet crucial period is essential for designing effective interventions and informing best practices to improve oral health for this vulnerable population.

1. INTRODUCTION

Oral health during pregnancy is critical for the overall health, well-being, and quality of life of the mother [1]. Although the prevalence of oral diseases in pregnancy varies in the literature, the American Dental Association reported that up to 75% of pregnant women have gingivitis [2]. Hormonal imbalances due to fluctuations in progesterone and estrogen increase the risks of pregnancy-associated gingivitis and benign oral gingival tumors [3]. Pregnancy not only leads to physiological changes but also affects health behaviors, such as dietary habits. Consuming a healthy diet may be difficult during pregnancy as women may have aversions towards certain foods, food cravings, heartburn, constipation, and hemorrhoids [4]. The increased frequency of nausea and vomiting experienced by pregnant women may result in acid-induced enamel erosion and dental caries [5-7]. Pregnant women are also at a heightened risk of tooth loss due to various physiological changes that occur over the course of pregnancy [8].

Poor oral health in women is significantly associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes [9-12]. Pregnant women with periodontitis are more likely to experience preterm birth and have an increased risk of having low-birth-weight babies [13-15]. Pregnant women with untreated dental infections are more likely to experience sepsis, preeclampsia, and miscarriages [16]. Poor oral health in pregnant women not only impacts the health and well-being of the mother and her infant but can also affect the oral health of her child [17]. The cariogenic bacteria in active carious lesions in a mother’s mouth can be transmitted to her infant via saliva. Early acquisition of these bacteria, combined with inadequate oral hygiene and dietary practices, can lead to early childhood caries and necessitate extensive dental care at a young age [18].

Dental service utilization is a global health challenge that predicts oral health outcomes [19]. The dental care for women of childbearing age is not being prioritized as a core component of prenatal care [20]. Approximately 50% of pregnant women experience dental problems worldwide, and more than half of women have poor dental service attendance during pregnancy [21-23]. Oral care utilization is influenced by demographic, socioeconomic, psychological, and behavioral factors, such as age, race, ethnicity, treatment costs, health insurance coverage, and pre-pregnancy oral hygiene habits [24, 25]. Perceived need, preexisting oral health problems, and history of prior dental visits are also major predictors of prenatal oral care utilization [22, 26, 27].

Although studies have reported low dental service utilization among pregnant women globally, there is a lack of comprehensive data on dental service use specifically among pregnant women attending PHCs in Saudi Arabia. Previous research has largely focused on dental clinics or hospital settings, with limited attention given to community-based PHC settings where most pregnant women receive their prenatal care. Moreover, barriers specific to the Saudi healthcare context, such as cultural perceptions, health system integration, and provider knowledge, remain underexplored. This study aims to fill this gap by providing evidence on the patterns and barriers of dental care utilization among pregnant women attending PHCs in Saudi Arabia.

In this study, we examined the utilization of oral health services by women attending primary healthcare centers (PHCs) in Saudi Arabia before, during, and after their pregnancy and identified the barriers associated with access to dental care.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study Population and Sample Selection

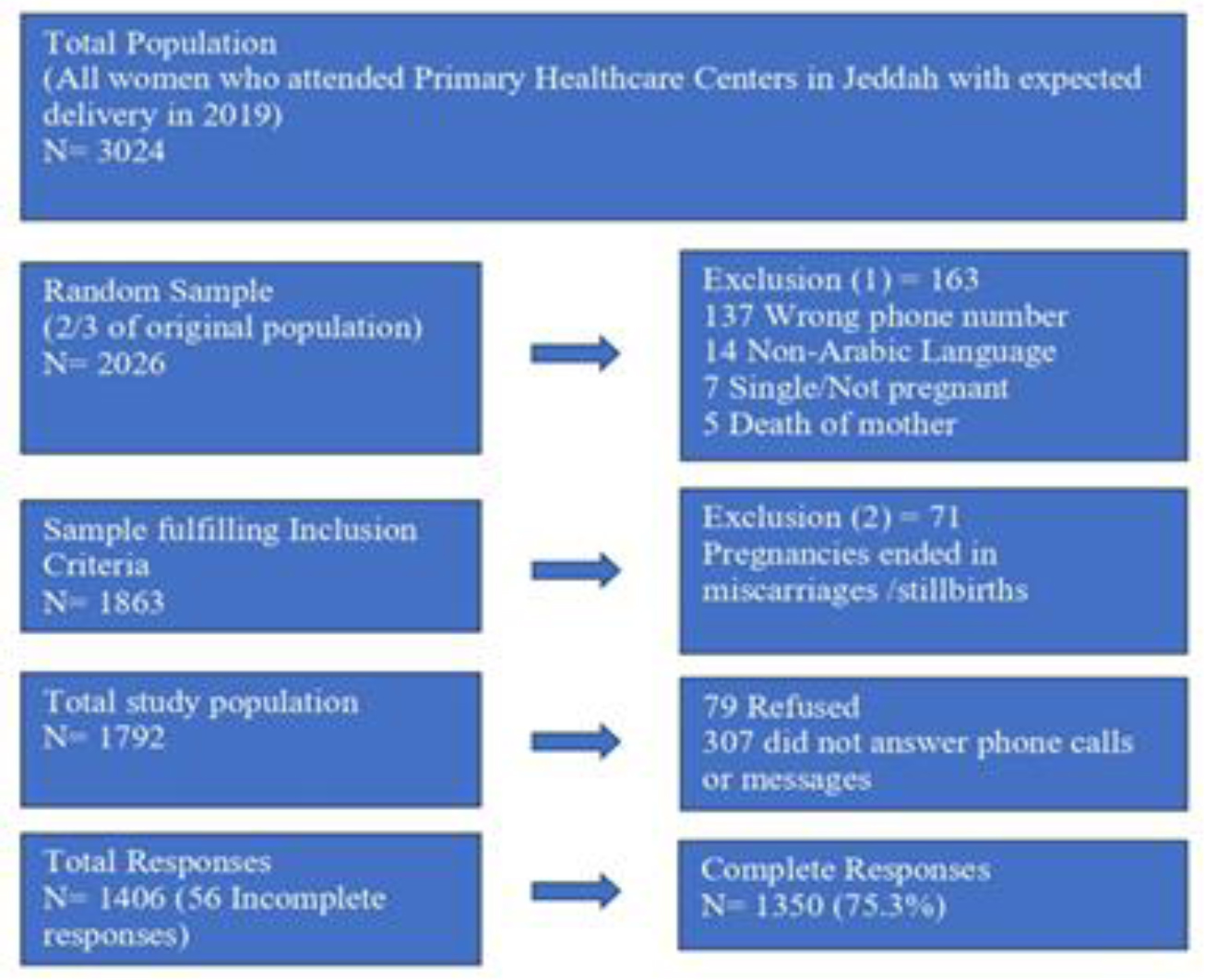

The Ministry of Health (MOH) oversees health care delivery in Saudi Arabia. It is responsible for formulating health policies and managing health infrastructure. There are five general hospitals funded by the MOH in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Each hospital is linked to a network of PHCs, which provide free preventive health care, treatment health services, such as management of chronic diseases, antenatal care, well-baby care, and dental services, and health promotion services. At the time of the study, there were 46 active PHCs in Jeddah. A list of the names and contact information of all mothers who attended antenatal care clinics in 2018-2019 was obtained from the directors of the PHCs. The sampling framework comprised 3024 women. A random sample of 2026 women, which comprised two-thirds of the original population, was selected for this study. Pregnant women were eligible to participate in the study if they had a pregnancy that ended in a live birth, had a working mobile phone number, spoke the Arabic language, and agreed to participate in the study. After applying our inclusion criteria and excluding those who did not meet the criteria, we had a sample of 1,792 women. Upon calling these eligible participants, 79 participants refused to participate, and 307 did not answer calls or messages. We received 1406 responses, of which 56 were incomplete. The final study sample consisted of 1350 participants, yielding a response rate of 75% (Fig. 1).

Process of selection of the study sample.

The figure illustrates the steps and selection criteria used to achieve the final study sample. We started with 3024 women who attended primary healthcare centers (PHCs) in Jeddah in 2019, and based on the multiple criteria, 1350 participants were selected as the final sample for the study.

2.2. Study Design and Ethical Approval

A cross-sectional study design was used to assess the utilization of dental services by women who attended PHCs in Jeddah for antenatal care during 2018-2019. The ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of King Abdulaziz University Faculty of Dentistry Research Ethics Committee [070-07-20] and the Institutional Review Board at the Ministry of Health [20-591E]. In addition, research clearance was obtained from the directors of research centers in each of the five government hospitals, and an email was sent to the directors of the PHCs to explain the purpose of the study and solicit their cooperation.

2.3. Survey Development and Administration

We used SurveyMonkey online software (http://www.surveymonkey.com) to create a structured quantitative questionnaire. It was translated from English to Arabic and then back-translated into English to ensure that the meaning was retained [39]. The online survey assessed participants’ dental care use in the six months before pregnancy, during pregnancy, and after their pregnancy, and identified factors that affect utilization of dental care during these time periods. The questionnaire for this study was adapted from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) [23]. Additional questions were added to address our study objectives. The online survey was pretested among a similar population to assess its clarity and suitability for participants, ease of navigation, and to estimate the time required to complete it. An electronic link to the online survey, along with the cover letter and informed consent, was sent to the participants via the WhatsApp messaging application (https://www.whatsapp.com). If the participant did not respond to the message, the research team members called the participant a maximum of 10 times on different days and at various times of the day before considering the number as not working. The actual participation in the study indicated their consent. Data collection started in February 2021 and was completed in January 2022. The data were exported for analysis to IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0.0.0, Armonk, NY: IBM. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

2.4. Study Variables

2.5. Oral Health Status

Existing oral health problems during pregnancy or six months before getting pregnant were reported as a dichotomous yes/no response. These included toothache, dental caries, gingival inflammation, and the need for tooth extraction. For analytical purposes, we created three composite variables: “any dental problem before pregnancy,” “any dental problem during pregnancy,” and “any dental problem before or during pregnancy.”

2.6. Oral Health Knowledge

Six statements were used to assess participants’ oral health knowledge. These statements were: (1) Dental treatment is safe during pregnancy, (2) Oral health affects general health, (3) Gum disease in pregnancy is related to preterm birth and/or low birth weight, (4) Women are at a higher risk for cavities and gum disease during pregnancy, (5) The second trimester is the ideal time for getting dental care, and (6) A mother with active cavities can spread bacteria that cause cavities to her baby. Most of these statements were adapted from previous studies of oral health knowledge of pregnant women [13, 17, 22, 26-28]. The sum of scores of all statements was calculated, and a composite score for oral health knowledge was formulated. The score ranged from 0 to 6, with a higher score indicating better oral health knowledge among the participants.

2.7. Regular Medical Checkup and Participants’ Medical History

Respondents were asked if they had a regular medical checkup in the six months preceding their pregnancy, and responses were recorded as yes/no. The presence of anemia, bronchial asthma, diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease was noted. These conditions were recorded as a yes or no response. For analytical reasons, a new composite variable “have any chronic disease” was created, and coded as yes, if participants reported having any chronic disease, and no, if they had none.

2.8. Oral Health Care Promotion by Prenatal Health Providers

The participants were asked if a prenatal health provider had advised them to visit a dentist during their pregnancy, and their responses were recorded as a binary yes/no.

2.9. Demographic Data

Demographic characteristics included age, level of educational attainment (elementary school diploma, middle school diploma, high school diploma, bachelor’s degree, and post-graduate degree), nationality (Saudi Arabian/non-Saudi Arabian), family monthly income in Saudi Riyals (SR; 1$=3.75 SR) (≤5,000, 5,001-7,000, 7,001-10,000, 10,001-15,000, 15,001-20,000, >20,000), and having a medical insurance (yes/no). Health insurance in Saudi Arabia typically includes dental coverage. For analytical purposes, the level of educational attainment was combined into three categories: <12 years of education, 12 years of education, and >12 years of education. Similarly, monthly income was consolidated into four groups: ≤5,000 SR, 5,001-7,000 SR, 7,001-10,000 SR, and >10,000 SR.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics in the form of frequencies and proportions for categorical variables and means and standard deviations for continuous variables were calculated. We examined the types of dental problems reported by the women in our study and compared them before and during pregnancy. A paired-samples t-test was used to check for differences in proportions between dental problems before and during pregnancy. We conducted Pearson’s χ2 test for categorical variables and the Pearson correlation coefficient for continuous variables to examine the associations between having a dental visit during pregnancy and selected characteristics. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and results with p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

A correlation matrix was calculated to assess correlations between independent variables. We used an adjusted binomial logistic regression model to quantify the association between independent variables and having a dental visit during pregnancy.

3. RESULTS

Table 1 presents the descriptive characteristics of our study participants. Most women were Saudi (88.7%, N = 1198), and their mean age was 32.0 years (standard deviation [SD] = 5.73). Almost half of them (47.9%, N = 647) had more than 12 years of education. Furthermore, 42.5% (N = 574) of the women had a family monthly income of up to 5,000 SR, whereas only 13.4% (N = 181) had an income greater than SR 10,000. Nearly one in five women (18.7%, N = 253) reported having anemia, and 5.5% (N = 74) had bronchial asthma.

Table 2 presents the reported dental problems of study participants before and during pregnancy. About 38.0% (N-515) and 51.3% (N = 693) of women visited a dentist before and after pregnancy, respectively. Only 31.0% (N = 419) had a dental visit during pregnancy, and among those, most (70.6%, N = 296) had a dental checkup only. During pregnancy, 49.5% (N = 668) reported experiencing a toothache, representing a significant increase of 3.6% compared to pre-pregnancy estimates (p < 0.01). The proportion of women who reported a need for tooth extraction during pregnancy was 35.3% (N = 477), a significant decrease of 5.0% compared to the proportion (40.4%, N = 545) reported before pregnancy (p < 0.001). The proportion of women with gum problems during pregnancy remained the same as before pregnancy (26.7%, N=360 vs. 27.3%, N = 369, p >0.05). The difference in proportions for tooth decay before and during pregnancy was 2.2% (57.0%, N = 770 vs. 54.8%, N = 740, p =0.05).

| Participants’ Characteristics | Statistic |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (standard deviation) | 31.98 (5.73) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| < 12 years of education | 234 (17.3) |

| 12 years of education | 469 (34.7) |

| > 12 years of education | 647 (47.9) |

| Family monthly income, n (%) | |

| ≤5,000 SR | 574 (42.5) |

| 5,001 – 7,000 SR | 307 (22.7) |

| 7,001 – 10,000 SR | 288 (21.3) |

| > 10,000 SR | 181 (13.4) |

| Nationality, n (%) | |

| Saudi | 1198 (88.7) |

| Non-Saudi | 152 (11.3) |

| Health insurance, n (%) | |

| No | 1188 (88.0) |

| Yes | 162 (12.0) |

| Past medical history, n (%) | |

| Anemia | |

| No | 1097 (81.3) |

| Yes | 253 (18.7) |

| Bronchial asthma | |

| No | 1276 (94.5) |

| Yes | 74 (5.5) |

| Diabetes | |

| No | 1327 (98.3) |

| Yes | 23 (1.7) |

| Hypertension | |

| No | 1315 (97.4) |

| Yes | 35 (2.6) |

| Heart disease | |

| No | 1346 (99.7) |

| Yes | 4 (0.3) |

| Any medical condition (anemia, asthma, diabetes, hypertension, heart disease), n (%) | |

| No | 1005(74.4) |

| Yes | 345(25.6) |

| Oral health knowledge, mean (standard deviation) | 2.32 (1.28) |

Table 3 presents the results of the bivariate analyses. The prevalence of a dental visit during pregnancy was higher among women who reported having any dental problems before or during pregnancy compared to those who did not have any problems before or during pregnancy (34.4% vs. 21.8%; 36.6% vs. 15.1%, p <0.05, respectively). We also found that women who had a dental visit before pregnancy had a higher prevalence of having a dental visit during pregnancy compared to those who did not report a dental visit before pregnancy (48.2% vs. 20.5%, p <0.05). Among women who had a regular medical checkup before pregnancy, 35.5% had a dental visit during pregnancy compared with 27.3% who did not report having a medical checkup before pregnancy (p <0.05). Furthermore, women who were advised by a physician or nurse to visit a dentist during a prenatal visit had twice the prevalence of visiting a dentist during pregnancy compared to women who were not advised to do so (53.6% vs 26.3%, p < 0.05). Finally, women with higher oral health knowledge scores had a higher prevalence of dental service utilization during pregnancy compared to those with lower scores (p <0.001). None of the demographic factors nor having any medical conditions were found to be significantly associated with having a dental visit during pregnancy (Table 3).

| Dental Problem | Before Pregnancy (N, %) |

During Pregnancy (N, %)a |

|---|---|---|

| Any dental problem | ||

| No | 358 (26.5) | 351 (26.0) |

| Yes | 992 (73.5) | 999 (74.0) |

| Toothache | ||

| No | 730 (54.1) | 682 (50.5) |

| Yes | 620 (45.9) | 668 (49.5)** |

| Tooth decay | ||

| No | 580 (43.0) | 610 (45.2) |

| Yes | 770 (57.0) | 740 (54.8)* |

| Red, swollen, or bleeding gums | ||

| No | 981 (72.7) | 990 (73.3) |

| Yes | 369 (27.3) | 360 (26.7) |

| Tooth needs extraction | ||

| No | 805 (59.6) | 873 (64.7) |

| Yes | 545 (40.4) | 477 (35.3)*** |

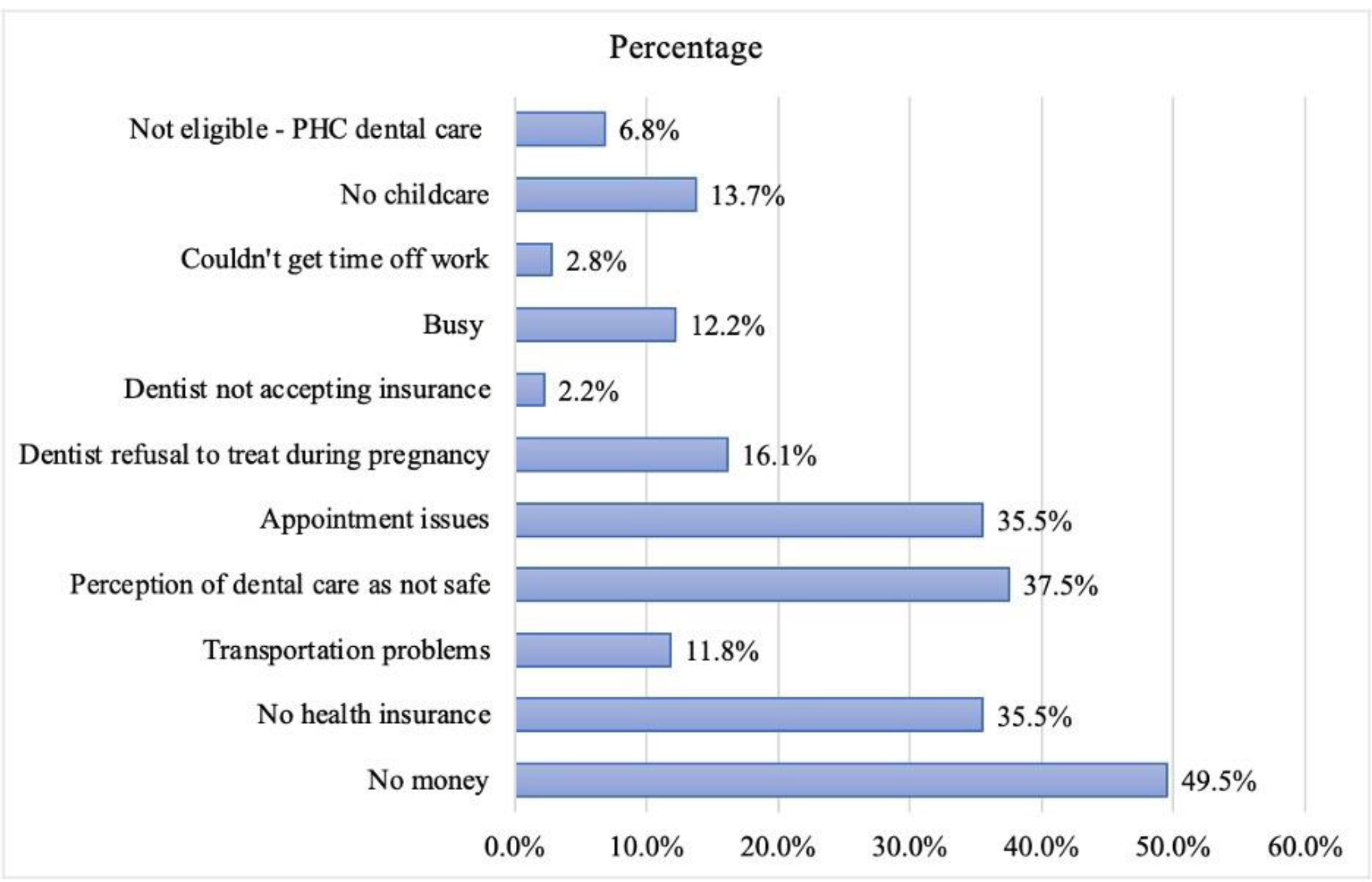

One-third of the study women (34.0%, N=459) needed oral health care during pregnancy but were unable to access it. Fig. (2) shows the barriers to dental care reported by these women. The most common barriers to seeking dental care were low income or having no money (49.5%, N=227), believing dental treatment is unsafe during pregnancy (37.5%, N=172), experiencing problems scheduling dental appointments (35.5%, N=163), and lacking dental coverage (35.5%, N=163). About 16.0% (N=74) of women reported that they were unable to obtain dental care during pregnancy because the dentist refused to treat them. In the open ‘other’ category for barriers to care, some participants described their reasons for not receiving care, such as:

| Characteristics | Had A Dental Visit During Pregnancy | p-valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (31.0%) | No (69.0%) | Prevalencec | ||

| Ageb | - | - | - | 0.857 |

| Education level | - | - | - | 0.415 |

| < 12 years of education | 74 (17.7%) | 160 (17.2%) | 31.6% | - |

| 12 years of education | 135 (32.2%) | 334 (35.9%) | 28.8% | - |

| > 12 years of education | 210 (50.10%) | 437 (46.9%) | 32.5% | - |

| Family monthly income | - | - | - | 0.843 |

| ≤5,000 SR | 173 (41.3%) | 401 (43.1%) | 30.1% | - |

| 5,001 – 7,000 SR | 96 (22.9%) | 211 (22.7%) | 31.3% | - |

| 7,001 – 10,000 SR | 89 (21.2%) | 199 (21.4%) | 30.9% | - |

| > 10,000 SR | 61 (14.6%) | 120 (12.9%) | 33.7% | - |

| Health insurance | - | - | - | 0.501 |

| No | 365 (87.1) | 823 (88.4) | 30.7% | - |

| Yes | 54 (12.9%) | 108 (11.6%) | 33.3% | - |

| Nationality | - | - | - | 0.25 |

| Non-Saudi | 41 (9.8%) | 111 (11.9%) | 27.0% | - |

| Saudi | 378 (90.2%) | 820 (88.1%) | 31.6% | - |

| Have any medical conditions (anemia, asthma, diabetes, hypertension, heart disease) | - | - | - | 0.597 |

| No | 308 (73.5%) | 697 (74.9%) | 30.6% | - |

| Yes | 111 (26.5%) | 234 (25.1%) | 32.2% | - |

| Oral health knowledgeb | - | - | - | 0.01 |

| Dental problems before pregnancy | - | - | - | - |

| Tooth decay | - | - | - | 0.001 |

| No | 153 (36.5%) | 427 (45.9%) | 26.4% | - |

| Yes | 266 (63.5%) | 504 (54.1%) | 34.5% | - |

| Toothache | - | - | - | <0.001 |

| No | 191 (45.6%) | 539 (57.9%) | 26.2% | - |

| Yes | 228 (54.4%) | 392 (42.1%) | 36.8% | - |

| Red, swollen, or bleeding gums | - | - | - | 0.005 |

| No | 283 (67.5%) | 698 (75.0%) | 28.8% | - |

| Yes | 136 (32.5%) | 233 (25.0%) | 36.9% | - |

| Tooth needs extraction | - | - | - | <0.001 |

| No | 216 (51.6%) | 589 (63.3%) | 26.8% | - |

| Yes | 203 (48.4%) | 342 (36.7%) | 37.2% | - |

| Any dental problems before pregnancy | - | - | - | <0.001 |

| No | 78 (18.6%) | 280 (30.1%) | 21.8% | - |

| Yes | 341 (81.4%) | 651 (69.9%) | 34.4% | - |

| Dental visit before pregnancy | - | - | - | <0.001 |

| No | 171 (40.8%) | 664 (71.3%) | 20.5% | - |

| Yes | 248 (59.2%) | 267 (28.7%) | 48.2% | - |

| Medical checkup before pregnancy | - | - | - | 0.001 |

| No | 202 (48.2%) | 537 (57.7%) | 27.3% | - |

| Yes | 217 (51.8%) | 394 (42.3%) | 35.5% | - |

| Advice by prenatal health providers to visit a dentist | - | - | - | <0.001 |

| No | 294 (70.2%) | 823 (88.4%) | 26.3% | - |

| Yes | 125 (29.8%) | 108 (11.6%) | 53.6% | - |

| Dental problems during pregnancy | - | - | - | - |

| Tooth decay | - | - | - | <0.001 |

| No | 150 (35.8%) | 460 (49.4%) | 24.6% | - |

| Yes | 269 (64.2%) | 471 (50.6%) | 36.4% | - |

| Toothache | - | - | - | <0.001 |

| No | 128 (30.5) | 554 (59.5%) | 18.8% | - |

| Yes | 291 (69.5%) | 377 (40.5%) | 43.6% | - |

| Red, swollen, or bleeding gums | - | - | - | <0.001 |

| No | 268 (64.0%) | 722 (77.6%) | 27.1% | - |

| Yes | 151 (36.0%) | 209 (22.4%) | 41.9% | - |

| Tooth needs extraction | - | - | - | <0.001 |

| No | 220 (52.5%) | 653 (70.1%) | 25.2% | - |

| Yes | 199 (47.5%) | 278 (29.9%) | 41.7% | - |

| Any dental problems during pregnancy | - | - | - | <0.001 |

| No | 53 (12.6%) | 298 (32.0%) | 15.1% | - |

| Yes | 366 (87.4%) | 633 (68.0%) | 36.6% | - |

Barriers to dental care for women who needed but could not access the care during pregnancy (n=459).

“I’m pregnant, they don’t do anything to you”, “I needed root canal treatment but because x-rays are harmful to the fetus, the dentist prescribed me an antibiotic”, “I went but the dentist didn’t look in my mouth, they just asked me questions”, “I had pain in my decayed molars but they didn’t do anything because I needed fillings and cleaning”, “the dentist refused to tighten my braces and told me it’s better not to do so during pregnancy, especially during the first trimester”, “all my appointments were refused until after delivery.”

Several mentioned that the dentist preferred not to treat them while they were pregnant to prevent potential harm to the fetus from X-rays, local anesthesia, filling material, and extractions. A few others explained that every time they went, there was something wrong with the dental unit or that the clinic was closed for maintenance.

Out of the 459 women who needed dental care during pregnancy but could not access it, the biggest barrier was lack of money (49.5%), followed by the perception that dental care is unsafe during pregnancy (37.5%).

Table 4 presents the multivariate logistic regression model of having a dental visit during pregnancy. The results of the correlation matrix showed weak correlations between the independent variables. It was found that women who had any dental problem before or during pregnancy had nearly three times the odds (OR: 2.68, 95% CI: 1.82-3.96) of having a dental visit during pregnancy compared to women who did not have any dental problems. In addition, women who visited a dentist before pregnancy and those who were advised by a physician or nurse at a prenatal visit to visit a dentist during pregnancy had three times higher odds of having a dental visit during pregnancy relative to those who did not visit a dentist before pregnancy or were not advised by a physician or nurse to visit a dentist (OR: 3.00, 95% CI: 2.33-3.86; OR: 2.79, 95% CI: 2.04-3.82, respectively). The odds of visiting a dentist during pregnancy increased by 16% among women who had higher oral health knowledge scores compared to their counterparts with lower scores (OR: 1.16, 95% CI: 1.05-1.29).

Table 4.

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.00 (0.97-1.02) | 0.51 |

| Education | ||

| 12 years of education | 0.77 (0.53-1.13) | 0.19 |

| > 12 years of education | 0.79 (0.54-1.17) | 0.24 |

| < 12 years of education | Reference | |

| Family income | ||

| 5,001 – 7,000 | 0.96 (0.69-1.34) | 0.82 |

| 7,001 – 10,000 | 1.01 (0.71-1.43) | 0.97 |

| > 10,000 | 1.24 (0.82-1.87) | 0.31 |

| < 5,000 | Reference | |

| Health insurance | ||

| Yes | 1.28 (0.87-1.88) | 0.22 |

| No | Reference | |

| Nationality | ||

| Saudi | 1.19 (0.78-1.82) | 0.41 |

| Non-Saudi | Reference | |

| Any chronic illness | ||

| Yes | 1.03 (0.77-1.37) | 0.87 |

| No | Reference | |

| Oral health knowledge | 1.16 (1.05-1.29) | 0.004 |

| Any dental problems before or during pregnancy | ||

| Yes | 2.68 (1.82-3.96) | <0.001 |

| No | Reference | - |

| Dental visit before pregnancy | ||

| Yes | 3.00 (2.33-3.86) | <0.001 |

| No | Reference | |

| Advice by prenatal health providers to visit a dentist | ||

| Yes | 2.79 (2.04-3.82) | <0.001 |

| No | Reference | |

| Regular medical checkup before pregnancy | ||

| Yes | 1.27 (0.99-1.64) | 0.07 |

| No | - | - |

4. DISCUSSION

Our study participants were enrolled from PHCs in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The sample primarily consists of healthy Saudi women of reproductive age from low- to middle-income socioeconomic backgrounds. Our study aimed to examine the utilization of oral health services by pregnant women and identify barriers to care. Even though most of the PHCs in Jeddah have dental clinics, and oral health care is integrated into primary care, three out of four women (74%) reported having dental problems, and only 31% of the women reported having a dental visit during pregnancy. The rate of dentist visits reduced drastically during pregnancy as compared to the pre- and post-pregnancy periods. We also observed that women who visited a dentist during pregnancy had pre-existing dental conditions, such as toothache, dental caries, periodontal disease, or teeth requiring extractions. During pregnancy, women only went for dental checkups and waited till they delivered to have more invasive services, such as dental restorations, extractions, or gum treatment. These findings align with previous research in Saudi Arabia, which highlights similar underutilization patterns due to misconceptions, fear, and lack of awareness [21, 28]. Comparisons with international studies help reveal whether these barriers are context-specific or universal. An Indian study reported similar challenges, particularly concerns about safety, low referral rates, and affordability [29]. Additionally, research from Nigeria highlights how cultural beliefs and geographic accessibility also affect utilization [30]. These shared patterns suggest that barriers are often universal, though context-specific interventions remain essential.

Our study highlighted that not only did most pregnant women present themselves for dental care when they were in absolute need of it, but there were others (34%) who were remotely unable to access dental care. Difficulties in scheduling dental appointments and long wait times to secure an initial or follow-up dental appointment were among the top-cited reasons that hindered the “affordable” and “integrated” dental care at the PHCs during pregnancy and throughout the lifespan of women. When the integration of oral health into prenatal healthcare is unsuccessful, patients tend to seek dental care in private dental settings. However, due to their low socioeconomic status, financial pressures, and lack of health insurance coverage, this vulnerable population faces limited access to dental health care, making it neither accessible nor equitable.

We also realized that the perception that dental treatment is unsafe during pregnancy prevented pregnant women from accessing dental care. Other reports on the utilization of dental services among pregnant women in Saudi Arabia have shown a similar finding [21, 31]. Poor oral health literacy among pregnant women and their ignorance of the adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with periodontal disease were reported [21, 32]. Whether this perception is related to independent predisposing factors within the women themselves, such as low education and income levels, or poor oral health literacy, or is rather imposed by dentists who refuse to provide dental care for pregnant women for various reasons, it nonetheless poses a significant barrier to the utilization of dental services.

Approximately 16% of the study women reported refusal to treat by a dentist as a barrier to dental care. A study on obstetrician-gynecologists reported that 77% of their pregnant patients had “declined” treatment by dentists [33]. Dentists may refuse to provide dental care for pregnant women out of fear of litigation, harm to the fetus, or lack of knowledge and understanding of the current guidelines about oral health care during pregnancy [34]. Declining necessary and timely preventive and treatment services or delaying them until after pregnancy raises ethical concerns and may cause potential harm to the overall health and well-being of the mother and her child [35]. Multiple professional dental and medical organizations, such as the American Dental Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, have provided practice guidelines for the dental management of pregnant women, establishing that dental diseases can be treated safely throughout pregnancy [36, 37]. Typically, dentists with inaccurate knowledge of the appropriateness of dental procedures during pregnancy tend to avoid caring for pregnant patients [34]. A national survey of U.S. dental school deans indicated limited clinical exposure of students to pregnant patients [38]. Furthermore, a survey of recent dental graduates from several dental colleges in Saudi Arabia found that 27% had never seen a pregnant woman in their clinic, and only 30% described their knowledge of oral healthcare for pregnant women as adequate [39]. Educating and training dental students in the proper care and management of pregnant women, and updating dental curricula with current guidelines on the care of pregnant women, is vital to ease their fears and uncertainties about the safety of dental procedures and medication use during pregnancy. A best practice approach report by the Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors (ASTDD) for improving perinatal oral health recommends developing perinatal oral health competencies and integrating them into dental school, dental hygiene education, and training, as well as board certification and continuing education courses [40]. Ensuring a competent and adequate dental workforce in the country is crucial for educating pregnant patients and enhancing their utilization of dental care.

Our analysis revealed that women with any dental problems had approximately three times the odds of visiting a dentist during pregnancy compared to those without dental problems. A review of the determinants of dental care attendance during pregnancy indicated a relationship between perceived need and dental visits during pregnancy [27]. Moreover, consistent with other studies [22, 41], we observed that women who had a pre-pregnancy dental visit were three times as likely to visit a dentist during pregnancy compared to those who did not. Previous research reported that only 13.7% and 18% of pregnant women performed routine dental visits during pregnancy [21, 41]. Routine dental visits by women improve their oral health literacy and motivate them to maintain lifelong satisfactory oral health practices for themselves and their families [37]. Women who regularly visit their dentists before pregnancy are more likely to seek adequate dental care during pregnancy and are better prepared to negotiate their oral health care needs with the dental team [42]. Finally, we found that oral health promotion by prenatal health providers had a substantial effect on dental visits during pregnancy. Women were nearly three times more likely to visit a dentist when they were advised to do so by their physician or nurse during their prenatal visit. Our finding agrees with previous research, which suggests that oral health counseling by prenatal health providers, such as obstetricians, family physicians, nurses, and midwives, influences the use of oral health services and decreases high-risk behaviors [43]. Therefore, promoting regular preventive dental care, strengthening oral health counseling during antenatal visits, and educating women are key strategies to increase knowledge of oral health, improve health outcomes for both the mother and the child during pregnancy, and ensure a caries-free new generation.

Our study findings provide the MOH with valuable information about the factors affecting the use of dental services among pregnant women attending PHCs. The provision of continuous, comprehensive, and coordinated dental services is essential for successful oral health integration. Case coordination to ensure that every pregnant woman who attends prenatal care at the PHC receives evidence-based oral health promotion interventions that focus on current prenatal oral health guidelines is crucial [16]. Likewise, the education and training of dental providers to act as advocates for the delivery of care to pregnant women should be ongoing and included in the training requirements for working in primary and secondary public healthcare settings. In addition, the MOH needs to reassess the dental health care workforce to meet the acute need for preventive, treatment, and oral health promotion services in the centers [44]. Effective integration of oral health care into prenatal care is vital to achieving the goal of affordable and accessible dental care for women during pregnancy and throughout their lifespan. Recommended policy interventions include mandatory oral health check-ups as part of prenatal care, awareness campaigns via mobile health apps and clinics [45], and subsidized private-sector dental services for pregnant women to complement the public sector and reduce potential delays in care. Additional measures could include short interprofessional training modules for PHC professionals [38]. While the findings are promising, the lack of supporting clinical trials highlights the need for further investigation to validate these results in clinical settings.

Our study’s large sample size and high response rate provide a strong foundation for reliable results. While our study focused on pregnant women attending PHCs in Jeddah, the findings may be generalizable to other urban areas in Saudi Arabia with similar healthcare structures and socioeconomic profiles. However, caution is advised when extrapolating these results to rural regions or different health system contexts, as variations in accessibility, cultural beliefs, and provider practices may influence dental care utilization patterns.

5. STUDY LIMITATIONS

The cross-sectional design of the study is a limitation that prevents inferring causality. Recall bias is another limitation; however, we limited the study sample to women who had a delivery two years before the beginning of data collection. Moreover, asking a pregnant woman about her visit to a dentist during pregnancy is considered a critical event that is less likely to be affected by recall bias. Therefore, recall bias is an unlikely explanation for the results of the present study.

CONCLUSION

Pregnancy is a time when women must engage with the healthcare system multiple times to ensure a safe delivery and a healthy baby. This is an opportunity to provide dental healthcare when the woman is most receptive and motivated to take good care of her health, out of regard and respect for the health of her unborn child. Due to the small number of studies that attempt to comprehend the full context of this issue, there is a significant shortage of understanding regarding oral health during pregnancy. Data at both the local and national levels are needed to monitor pregnant women's oral health status and their access to dental care. Integration of oral health care into the prenatal health care delivery system does not guarantee efficient utilization of oral health care. It is important to investigate efficient methods and best practices for enhancing pregnant women's access to dental treatment in primary healthcare settings. This is critical for reducing oral health disparities and improving the oral and systemic health of pregnant women and their children. Healthcare providers can enhance uptake by educating patients, encouraging regular dental referrals, and engaging in interprofessional training. Strengthening oral health within national maternal care policies is essential to ensure equitable access for all expectant mothers.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: D.E.A.A.: Conceptualization; L.M. and S.N.: Data collection; S.A.: Methodology; S.N.: Writing, reviewing, and editing; N.A.: Validation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| PHCs | = Primary Healthcare Center |

| MOH | = Ministry of Health |

| PRAMS | = Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Ethical approval was obtained from our institutional review board (IRB) of King Abdulaziz University, Faculty of Dentistry Research Ethics Committee [070-07-20], Saudi Arabia and the Institutional Review Board at the Ministry of Health [20-591e].

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Informed consent to participate in the research was obtained from the participants.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data and supportive information are available within the article.

FUNDING

The study is funded by a grant from the Deputyship for Research and Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia, and King Abdulaziz University, Deanship for Scientific Research, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (project number IFPHI-341-140-2020).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to appreciate the help provided by Dr. Floyd J. Fowler, Jr., former senior research fellow and director of the Center for Survey Research at UMass Boston. They would also like to acknowledge the support provided by the healthcare workers and the contribution of the study participants during this study.