All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

How Does Oral Health Status Correlate with Cognitive Decline in Individuals with Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease: An Umbrella Review

Abstract

Background

Issues pertaining to oral health have been recognised as a common concern among dementia patients. Past studies have indicated several mechanisms through which poor oral health could contribute to cognitive decline, such as systemic inflammation and direct effects on daily functioning and quality of life.

Methods

An umbrella review was conducted through an extensive search across a range of databases. The search strategy combined specific terms that would specifically pick out relevant studies for oral health and cognitive decline in dementia. A standardized tool to evaluate systematic reviews was applied to assess the quality and potential bias of the studies included.

Results

We included 8 reviews in our investigation, which revealed a complex relationship between oral health and cognitive decline in dementia. It was observed that poor oral health, characterized by high levels of dental plaque, gingival bleeding, and periodontal disease, was frequently associated with worse cognitive outcomes. There were some studies that focused on the inflammatory process as a bridge, while others stressed that oral health directly influences quality of life and cognitive performance. Variability in severity was noted for periodontal disease and its correlation to cognitive impairment, and in a few studies, a protective effect of good oral hygiene was reported.

Conclusion

The findings of this umbrella review confirm that poor oral health is indeed associated with cognitive decline among individuals with dementia. This association was mediated by pathways, such as systemic inflammation, which exacerbates neurodegeneration and directly impacts the quality of life and daily functioning. Such results underscore the need for comprehensive oral health care as well as regular assessments in the care setting for people with dementia as one potential way of preventing deterioration in cognition.

1. INTRODUCTION

An increasing body of research is examining the connection between dental health and cognitive performance, which is a reflection of the growing understanding of the interdependence of neuronal and systemic health [1]. Dementia is a complex condition that is primarily characterised by progressive cognitive deterioration. It presents severe challenges not only to the sufferer but also to carers and health services worldwide [2]. In recent times, there have been increasingly more research scientists studying potentially modifiable risk factors for dementia about its onset and progression [3-6].

The state of the oral cavity, in most instances, matters a great deal to health and the overall quality of life. It is crucial for communication, nutrition, and a life free from pain. Oral infections leading to tooth loss, periodontal disease, or oral infection can cause or exacerbate systemic inflammation, poor glycemic control, and malnutrition—all known to have an effect on brain health [4-6]. Besides being a gateway to the body, the mouth may contain bacterial infections that induce systemic inflammatory responses, one of the proposed mechanisms that relates dental health to brain health [7]. A few observational studies are available that support the hypothesis that oral health is directly related to cognitive function [8-10]. In addition, due to decreased motor skills and forgetfulness caused by cognitive decline in dementia, poor oral hygiene often occurs, worsening the condition of both oral and cognitive health [9].

The relevant literature in this regard presents a mixed picture despite the probable biological causes and observational evidence. This is because different studies have examined different populations, defined oral and cognitive health in different ways, and employed different assessment procedures [10]. Although systematic reviews in this field have made an effort to compile the information that is currently accessible, it is difficult to reach firm conclusions because of variations in their methodologies and conclusions [11-13]. This heterogeneity underlines the need for an umbrella review, or a review of previous systematic reviews, that can provide a complete synthesis and evaluation of data related to the link between dental health and cognitive decline in dementia.

Therefore, the aim of this umbrella review is to critically appraise and summarize the findings of various reviews on the association between the status of oral health and cognitive deterioration in patients with dementia and, finally, to uncover any consensus or differences between studies.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

To ensure transparency and reproducibility, we strictly adhered to the PRISMA guidelines in conducting this umbrella review [14]. Following these guidelines, a full review protocol was developed and registered, detailing the objectives of the study, requirements for study inclusion, and how the risk of bias would be evaluated. For this investigation, the PECO protocol (Population, Exposure, Comparator, Outcome) was outlined as follows:

2.1.1. Population

The study involved patients diagnosed with various forms of dementia, such as Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia, and others. The age, sex, or ethnic background of the patients was not limited in any way, thus including a diverse group of the dementia population.

2.1.2. Exposure

The primary exposure of interest was the status of oral health. This included a variety of conditions, such as periodontal disease, number of missing teeth, presence of dental caries, and general oral hygiene status.

2.1.3. Comparator

Considering the exploratory character of our evaluation, the presence of a comparator group was not required, but the comparators in this review were people with dementia who had comparatively better oral health conditions, as determined by the individual studies included in the review.

2.1.4. Outcome

The primary outcomes were measures of cognitive decline, which included both the progression of dementia and changes in specific cognitive functions.

The eligibility and exclusion criteria developed for this review are shown in Table 1.

2.2. Search Strategy across Databases

Table 2 demonstrates how the search strategy was formulated to include a combination of MeSH terms and keywords that use Boolean operators to ensure a thorough retrieval of relevant reviews as well as the databases used in the construction and conduct of the search process for our umbrella review.

| Criterion | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Study type | Systematic reviews, meta-analyses, scoping reviews | Single studies, editorials, case reports |

| Population | Reviews focusing on individuals diagnosed with any type of dementia | Reviews focusing on non-dementia populations |

| Exposure | Reviews assessing oral health status (e.g., periodontal disease, dental caries) | Reviews not specifically addressing oral health |

| Comparator | Reviews including comparisons based on levels of oral health | - |

| Outcome | Cognitive decline or progression of dementia as primary outcomes | Reviews not focusing on cognitive outcomes |

| Language | No limitation | |

| Publication date | ||

| Database | Search String |

|---|---|

| PubMed | ("Dementia"["MeSH Terms"] "OR" "dementia"["All Fields"]) "AND" ("Oral Health"["MeSH Terms"] "OR" "oral hygiene"["All Fields"] "OR" "periodontal diseases"["MeSH Terms"] "OR" "dental caries"["MeSH Terms"]) "AND" ("Systematic Review"["Publication Type"] "OR" "Meta-Analysis"["Publication Type"] "OR" "scoping review"["All Fields"]) |

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY ("dementia") "AND" TITLE-ABS-KEY ("oral health" "OR" "oral hygiene" "OR" "periodontal disease" "OR" "dental caries") "AND" TITLE-ABS-KEY ("systematic review" "OR" "meta-analysis" "OR" "scoping review")) |

| Web of Science | (TI="dementia" "AND" TI=("oral health" "OR" "oral hygiene" "OR" "periodontal disease" "OR" "dental caries") "AND" TI=("systematic review" "OR" "meta-analysis" "OR" "scoping review")) |

| Cochrane Library | ("dementia":ti,ab,kw "OR" "Cognitive Decline":ti,ab,kw) "AND" ("oral health":ti,ab,kw "OR" "oral hygiene":ti,ab,kw "OR" "periodontal diseases":ti,ab,kw "OR" "dental caries":ti,ab,kw) "AND" ("systematic review":ti,ab,kw "OR" "meta-analysis":ti,ab,kw "OR" "scoping review":ti,ab,kw) |

| PsycINFO | (DE "Dementia") "AND" (DE "Oral Health" "OR" DE "Oral Hygiene" "OR" DE "Periodontal Diseases" "OR" DE "Dental Caries") "AND" (DE "Systematic Review" "OR" DE "Meta-Analysis" "OR" DE "Scoping Review") |

| Embase | ('dementia'/'exp' "OR" "dementia") "AND" ('oral health'/'exp' "OR" 'oral hygiene' "OR" 'periodontal disease'/'exp' "OR" 'dental caries'/'exp') "AND" ('systematic review'/'exp' "OR" 'meta-analysis'/'exp' "OR" 'scoping review') |

2.3. Data Extraction Protocol

Data extraction was performed by two independent reviewers using a standardized form tested on several reviews before being implemented fully. Any discrepancies arising from the interpretation of data between the reviewers were solved through discussion or by consultation with a third reviewer to ensure accuracy and agreement in the data collected.

The data from each included a systematic review and meta-analysis comprised:

2.3.1. Bibliographic Information

This included the names of the authors, the year the study was published, and the country where the research was conducted.

2.3.2. Review Details

This included whether the study was a systematic review or a meta-analysis, the search strategy adopted, the databases used to search, and how many studies were finally included.

2.3.3. Demographic and Clinical Variables

These included information concerning the number of subjects, age ranges, gender distribution, diagnosed type of dementia, as well as the degree of cognitive impairment.

2.3.4. Oral Health Survey

It included information related to measures of oral health that were reported, such as the number and severity of gum disease, missing teeth, and the number of dental caries.

2.4. Bias Evaluation Methodology

Throughout the bias evaluation process for this study, the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses [15] was followed. To strengthen the strength and credibility of the review, this approach was applied stringently to evaluate the methodological quality, risk of bias, and limitations of the selected research.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study Selection Process

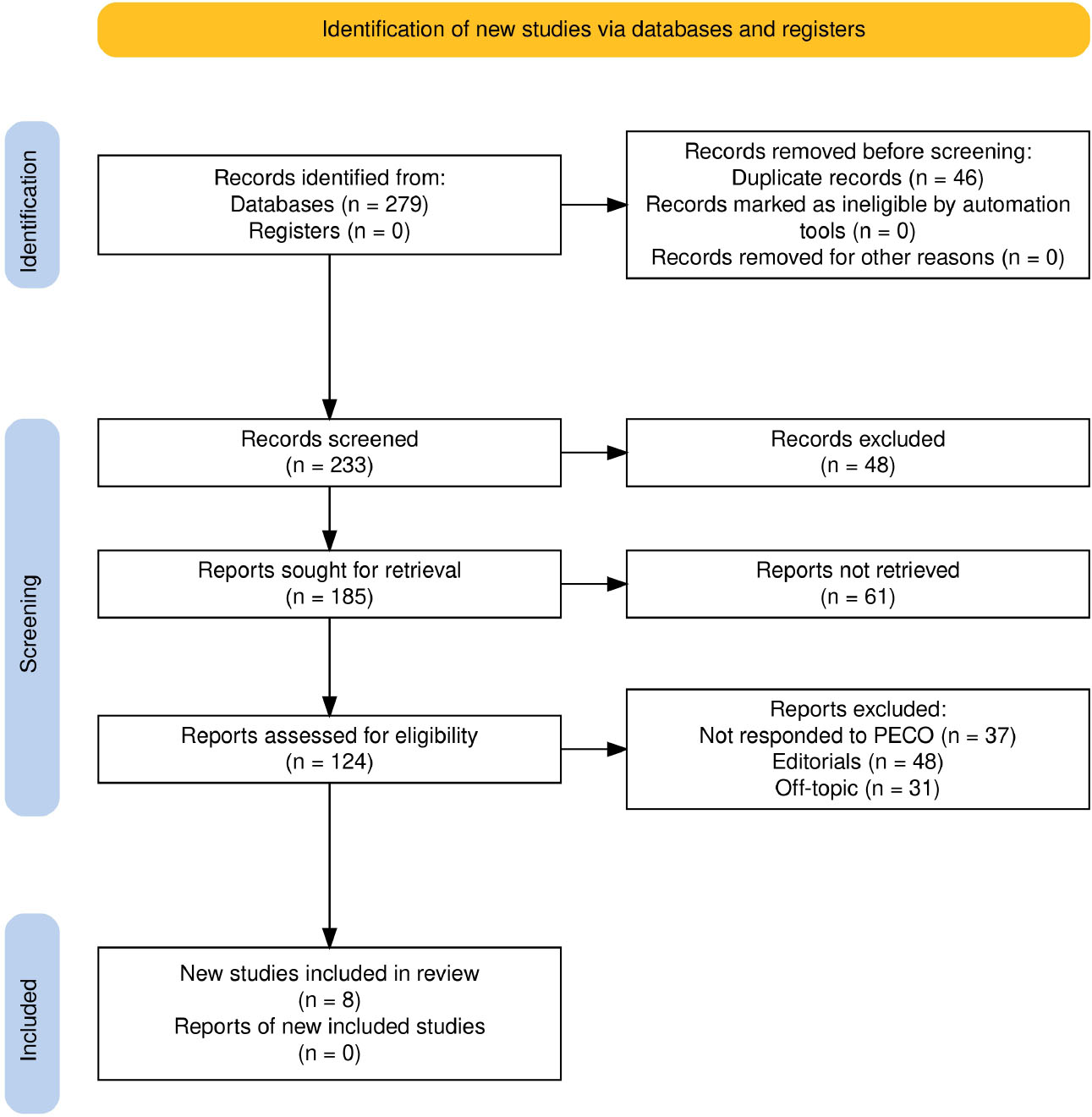

A total of 279 records were first identified from various databases, as Fig. (1) shows. A total of 46 duplicates were removed before the screening process. A total of 530 data reports were reviewed in the initial stage of screening. However, 48 of them were excluded because the full text could not be accessed. Hence, 185 reports were found and retrieved. Sixty-one of those reports could not be acquired. Next came the search for the remaining 124 reports, which were still qualified. Due to predetermined criteria, a large number of papers were eliminated from this evaluation: 37 studies did not meet the norms of the PICO framework, 48 were editorials, and 31 reports were off-topic. Eight reviews [16-23] that satisfied all inclusion requirements were allowed to be included in the review after this process.

3.2. Bias Assessment Observations

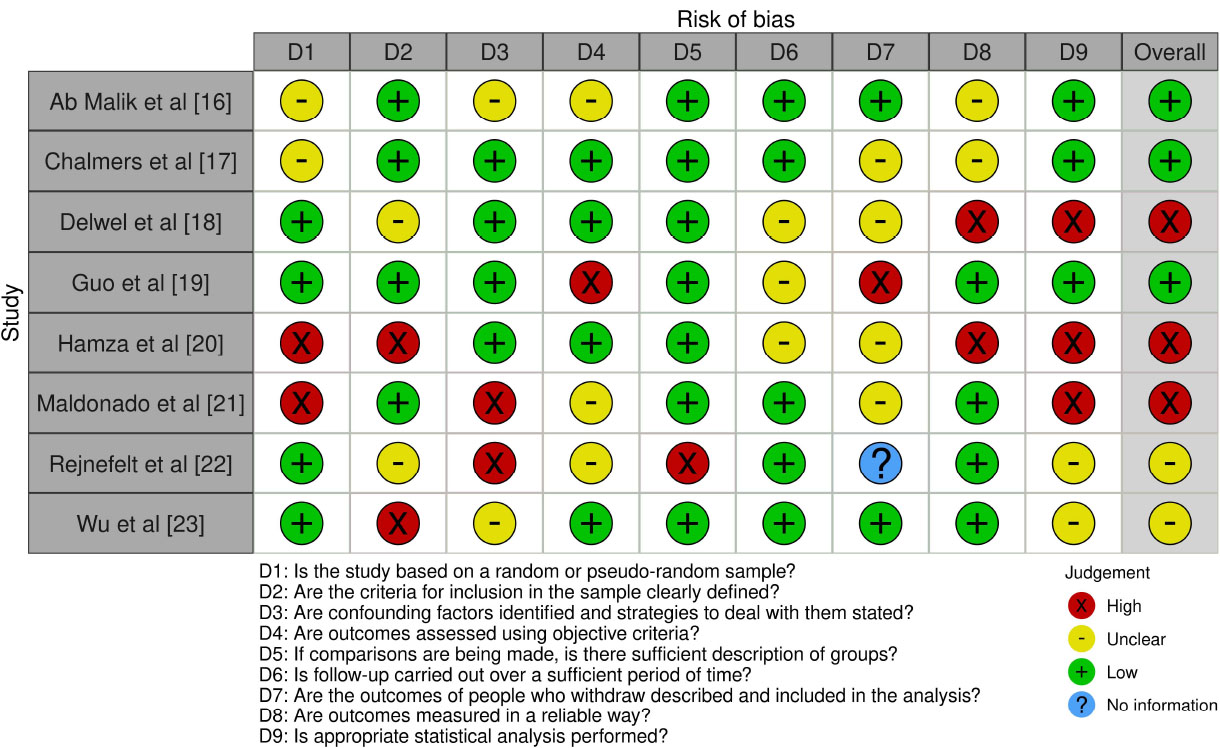

As shown in Fig. (2), the bias assessment of the included reviews highlighted variability in methodological rigor and the presence of potential biases. Reviews by Hamza et al. [20] and Maldonado et al. [21], and to a lesser extent, Delwel et al. [18], demonstrated higher methodological quality, particularly in sampling, outcome assessment, and statistical analysis. Conversely, Ab Malik et al. [16] and Chalmers et al. [17] received lower scores, reflecting substantial potential biases. These biases primarily stemmed from limitations in inclusion criteria, inadequate handling of confounding factors, and insufficient descriptive information on comparator groups. Furthermore, issues with the validity of outcome measurements and follow-up durations were noted in many studies. However, Guo et al. [19] excelled in certain methodological criteria, notably in the comprehensive assessment of periodontal indices.

Study selection process for this review as per PRISMA guidelines.

Bias assessment observations across the included reviews.

3.3. Summary of Incorporated Studies

Table 3 summarizes the included reviews [16-23]. Findings from Ab Malik et al. [16] revealed a higher prevalence of periodontal disease in dementia patients, characterized by increased plaque index (PI), bleeding on probing (BOP), pocket depth (PD), and clinical attachment loss (CAL). Chalmers et al. [17] emphasized the need for regular oral health assessments using standardized tools like the Brief Oral Health Status Examination to improve management in dementia care settings. Reviews by Delwel et al. [18] and Guo et al. [19] identified oral health challenges in elderly dementia patients, including plaque accumulation, periodontitis, and decreased salivary flow, underscoring the need for improved caregiver education and targeted periodontal interventions.

Studies by Hamza et al. [20] and Maldonado et al. [21] linked poor periodontal health, as reflected by significant differences in PPD, BOP, CAL, and PI, with an increased risk of cognitive impairment. These studies highlighted the role of inflammation as a mediator between periodontal disease and cognitive decline. Rejnefelt et al. [22] focused on oral health challenges in advanced dementia stages, such as reduced saliva flow and plaque accumulation, while noting no significant changes in tooth loss or caries. Wu et al. [23] reported mixed findings regarding the impact of oral health on cognitive decline, emphasizing the need for consistent methodologies to clarify these associations.

3.4. In-depth Assessments on Oral Health and Dementia Correlation

Table 4 illustrates the relationship between oral health status and dementia across included reviews [16-23]. Ab Malik et al. [16] examined multiple periodontal indices (e.g., DP, gingival bleeding, PD, CAL, CPI, and MABL) and found that severe periodontal disease is associated with cognitive deterioration. Guo et al. [19] linked periodontitis to cognitive impairment, highlighting systemic inflammation as a key mediator. Their findings showed that worse periodontal health, measured by indices, such as GI, PI, BOP, and CAL, significantly increased the risk of cognitive decline (OR = 1.77, p < 0.01).

Delwel et al. [18] identified a dual relationship where poor oral health in dementia patients exacerbates oral pathologies, such as candidiasis, stomatitis, and xerostomia, which in turn complicates dementia management. Hamza et al. [20] provided a comprehensive view of factors like oral hygiene, dentition, and salivary markers, suggesting that inflammatory pathways play a critical role in linking oral health decline to Alzheimer’s progression. Similarly, Maldonado et al. [21] observed significant increases in BOP, CAL, GBI, and PPD among dementia patients, supporting the association between poor periodontal health and cognitive degradation.

Rejnefelt et al. [22] reported a general deterioration in oral health among dementia patients, particularly in terms of

| Study ID/Refs. | Focus of Review | Database(S) Used | Key Findings related to Oral Health and Dementia | Overall Inference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ab Malik et al [16] | Periodontal disease in dementia | Medline/Pubmed, Web of Science, Scopus, Cochrane Library, Embase/OVID | Higher incidence of periodontal disease (higher PI, BoP, PD, CAL) in dementia patients | Moderate quality with lower comparability scores; highlights inflammation in dementia |

| Chalmers et al [17] | Oral health assessment tools in residential aged care | Electronic databases (1980-2002), secondary search | Emphasizes the necessity of regular oral assessments by trained carers; highlights the Brief Oral Health Status Examination as a comprehensive tool | Supports the use of specific tools for dementia patients; need for continued tool evolution |

| Delwel et al [18] | Oral hygiene and health in elderly with dementia | PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane Library | Reports high levels of gingival bleeding, periodontitis, plaque, candidiasis, stomatitis, and reduced salivary flow in elderly with dementia | Suggests a significant prevalence of oral health issues; underscores need for better caregiver education |

| Guo et al [19] | Link between periodontal disease and cognitive impairment/dementia | PubMed, Web of Science, Embase | Found strong association between periodontitis and cognitive impairment; moderate/severe periodontitis notably linked with dementia | Highlights periodontitis as a risk factor for cognitive impairment, with detailed statistical analysis |

| Hamza et al [20] | Epidemiology of oral health in dementia | PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus | Oral health deteriorates in AD/dementia; periodontal diseases and edentulousness linked with cognitive decline. | Broad study period and multiple conditions examined; highlights need for special oral care in dementia. |

| Maldonado et al [21] | Periodontitis association with dementia | MEDLINE, EMBASE | Dementia patients show worse periodontal health than controls; significant differences in PPD, BOP, GBI, CAL, and PI. | High relevance with strong statistical backing; suggests need for periodontal screening in dementia. |

| Rejnefelt et al [22] | Oral health in dementia patients in facilities | MEDLINE (Entrez PubMed) | Dementia patients in facilities experience worse oral health, including higher caries incidence and reduced saliva flow. | Limited data but underscores increased oral health issues in advanced dementia stages. |

| Wu et al [23] | Longitudinal studies on oral health and cognitive decline | PubMed/Medline, CINAHL | Mixed findings on the impact of oral health on cognitive decline; methodological differences noted among studies. | Highlights need for consistent methodologies to clarify associations between oral health and cognition. |

| Study ID/Refs. | Dental/Periodontal Indices | Cognitive Impairment Associations | Overall Findings | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ab Malik et al. [16] | Dental Plaque, Gingival Bleeding, Periodontal Pocketing, CAL, CPI, Periodontal Disease Severity, MABL, Inflammatory Mediators | Correlation with cognitive decline | Majority report significant differences: higher plaque, gingival bleeding, deeper pockets, and greater CAL in dementia patients. Mixed results for CPI. No significant differences in MABL, but high inflammatory mediators associated with decline. | Significant differences in plaque, gingival bleeding, CAL (p < 0.05). Mixed results for CPI (p > 0.05). |

| Guo et al. [19] | Periodontitis association with Cognitive Impairment, Periodontal Status (GI, PI, BOP, GBI, CPI, CAL, PPD) | Higher odds of cognitive impairment with periodontitis | OR = 1.77 for cognitive impairment, consistent worse periodontal status in dementia patients across multiple indices. Sensitivity analysis shows high heterogeneity for PPD. | Statistically significant association for OR = 1.77 (p < 0.01). High heterogeneity in PPD analysis (p > 0.05). |

| Delwel et al. [18] | Plaque Indices (Visible Plaque, O’Leary, Oral Hygiene Index), Oral Care Assistance, Oral Pathology (Candidiasis, Stomatitis, Xerostomia), Salivary Flow, Periodontal Health | Increased need for care and pathology in dementia | Significant findings in plaque accumulation and need for oral care assistance. Mixed results in periodontal health, with significant instances of oral pathology and reduced salivary function noted in dementia patients. | Significant plaque accumulation and oral care needs (p < 0.01). Mixed results for periodontal health (p > 0.05). |

| Hamza et al. [20] | Oral Hygiene Status, Dentition, Periodontal Health, Prosthesis Status, Oral Pathologies, Salivary Status, Oral Pathogens, Inflammatory Markers | Notable decline in oral health in Alzheimer's patients; potential links between oral health and Alzheimer's disease progression. | Higher plaque scores, increased bleeding on probing, fewer natural teeth, and higher DMFT scores in Alzheimer's patients. Significant correlations between poor periodontal health (higher GI, PI, PPD, CAL) and Alzheimer's progression. Elevated inflammatory markers in patients with poor oral health. | Significant differences in GI, PI, PPD, CAL (p < 0.001). Elevated inflammatory markers linked to poor health (p < 0.01). |

| Maldonado et al. [21] | Periodontal Indices (BOP, CAL, GBI, PI, PPD) | Worse periodontal health linked to cognitive decline | Statistically significant differences with 35.72% increase in BOP, 2.53 mm increase in CAL, 6.98% increase in GBI, 15.95% increase in PI, and 1.46 mm increase in PPD in dementia patients. Standardized mean differences showed a mean difference of 0.53 indicating worse periodontal health in dementia patients. | Statistically significant increases in BOP, CAL, GBI, PI, PPD (p < 0.001). Mean difference of 0.53 (p < 0.05). |

| Rejnefelt et al. [22] | Dental Status, Caries, Saliva Flow, Oral Hygiene, Periodontal Health, Mucosal Alterations | Persistent worsening of oral health in dementia; no significant changes in tooth loss and caries in some studies. | Higher levels of plaque, gingival bleeding, and calculus in dementia patients. Common occurrence of denture stomatitis. Significant reductions in saliva flow rates noted over time. Longitudinal data show increasing oral hygiene and periodontal issues in dementia patients. | Significant reductions in saliva flow (p < 0.01). Mixed results for caries and tooth loss (p > 0.05). |

| Wu et al. [23] | Impact of Oral Health on Cognitive Status: Teeth Count, Caries, Mastication, Periodontal Disease, Personal Dental Care | Mixed results on the impact of oral health on cognitive status; some studies link fewer teeth and periodontal issues with cognitive decline. | Varied findings on the association between teeth count and cognitive decline. Development of caries correlated with lower cognitive test scores. Improved personal dental care associated with less pronounced cognitive decline. | Mixed results for teeth count (p > 0.05). Significant correlation for caries and cognitive decline (p < 0.01). |

saliva flow and plaque accumulation, while findings on tooth loss and caries were inconsistent. Wu et al. [23] explored dental health factors, such as teeth count, mastication, and caries, noting complex and mixed results. Improved dental care was linked to less severe cognitive decline in some studies, but findings lacked consistency.

4. DISCUSSION

The scope and character of these relationships varied, despite the fact that all of the evaluations included [16-23] recognised a general pattern of worsening dental health in dementia patients and its possible influence on cognitive decline. For example, Ab Malik et al. [16] and Hamza et al. [20] were more concerned with the inflammatory component and proposed that cognitive issues were caused by systemic inflammation. On the other hand, periodontal disease as a risk factor for cognitive impairment was the subject of sound statistical investigations by Guo et al. [19] and Maldonado et al. [21]. Wu et al. [23] specifically emphasised the preventive potential of maintaining proper oral hygiene, while Delwel et al. [18] and Rejnefelt et al. [22] emphasised the gradual nature of oral health loss in dementia. The complex relationship between oral health and cognitive functioning in ageing populations is presented by this varied but related body of studies.

According to Ab Malik et al. [16], inflammation may play a part in dementia development, suggesting that inflammatory mediators linked to poor dental health may also play a role in cognitive decline. Similar findings were proposed by Hamza et al. [20], who also pointed out that a possible inflammatory pathway connecting periodontitis and neurodegeneration may be highlighted by the elevated inflammatory markers in Alzheimer's patients with poor oral health. Guo et al. [19] provided a robust statistical foundation with an odds ratio calculation, highlighting the fact that periodontitis provides a substantial risk factor towards cognitive impairment. Their findings were strikingly comparable to those of Maldonado et al. [21], who assessed the development of periodontal diseases in patients suffering from dementia and found substantial statistical evidence linking periodontal health to cognitive deterioration. In addition to Guo et al. [19] reporting significant variation in probing pocket depth, both publications highlighted periodontal disease as a critical factor in maintaining cognitive status; however, Maldonado et al. [21] did not address this.

According to Delwel et al. [18] and Rejnefelt et al. [22], dementia patients have a high rate of oral health issues. Rejnefelt et al. [22] documented longitudinal decline, while Delwel et al. [18] concentrated on the necessity of offering oral care support. Although Delwel et al. [18] also reported conflicting findings on periodontal health, which tend to imply less of a causal relationship than what Rejnefelt et al. [22] described, these studies were comparable in that they concluded that dementia causes a steady loss in oral health. By presenting conflicting results about the correlation between tooth count and cognitive decline and pointing out that better personal dental care was linked to less severe cognitive decline, Wu et al. [23] offered a nuanced perspective. This study stood out from others because it raised the possibility that maintaining proper dental hygiene could prevent cognitive decline, an idea that has not been fully explored in previous research.

According to a review of the literature, those who have dementia typically have poor dental health [24-26]. The state of oral health is not substantially impacted by the type of dementia, such as vascular dementia or Alzheimer's disease [24, 27, 28]. However, poorer oral hygiene, which is characterised by increased plaque accumulation and more common oral illnesses, seems to be associated with a higher degree of cognitive impairment [24-29]. In the study by Srisilapanan et al. [30], there was a noteworthy deviation from the norm. The patients were attending a memory clinic that also included dental care, which resulted in comparatively better oral health results when compared to the general dementia population.

The way of life of people with dementia also affects their dental health; there are conflicting findings about whether living in a nursing home or the community has an impact on oral health outcomes [31, 32]. According to some research, there are no appreciable variations in oral health based on where a person lives [33-35], but other studies have found that residents of nursing homes have poor oral health [33, 36], which may be related to the higher levels of cognitive and functional impairments observed in these environments [37].

The capacity to maintain oral hygiene is impacted by cognitive decline in dementia because normal dental care tasks become more difficult due to worsening executive functions, working memory, attention, and motor abilities, including apraxia and diminished hand grip strength [38-40]. Increased plaque accumulation is frequently the outcome of this [41, 42], and it is a major cause of gingivitis and can develop in periodontitis [43]. Maintaining oral health in people with dementia is essential for both dental and general health reasons, as periodontitis has been linked to systemic disorders, such as cardiovascular illnesses and type 2 diabetes mellitus [4].

A useful point of reference is provided by the results of Lin et al. [44], who also conducted an umbrella review on the more general subject of oral-cognitive linkages. The intricacy and diversity of variables influencing the relationship between dental health and cognitive performance were acknowledged by the authors of both our review and the study by Lin et al. [44]. Periodontal disorders are mentioned as a significant risk factor for cognitive impairment in both reviews. Similar to Lin et al., we discovered that, as shown in the research by Guo et al. [19] and Maldonado et al. [21], a significant deterioration in dental health was one of the most important factors linked to cognitive decline.

By concentrating on dementia patients, our evaluation provided a more concentrated examination of the effects of dental health on this demographic. The study by Lin et al. [44], on the other hand, was more comprehensive, taking into account a variety of cognitive dysfunctions and elements, such as masticatory function and the oral microbiome that were not the main focus of our review. Additionally, the statistical analysis and longitudinal data in our research brought to light the progressive loss in oral health among dementia patients, a feature that Lin et al. [44] did not fully address. The review was able to go further into specifics on specific disease mechanisms because of its focused emphasis. For example, Ab Malik et al. [16] and Hamza et al. [20] highlighted inflammation pathways, while Wu et al. [23] discussed the protective benefits of keeping good oral hygiene. A slight but significant advantage over the widely utilised strategy taken by Lin et al. [44] is that this attention allowed for a more precise delineation of prospective treatment and preventive interventions that are more closely targeted to the demands of a dementia patient.

A more specific examination of periodontal health as a risk factor for dementia and cognitive decline was provided by Asher et al. [26], who carried out a targeted evaluation of the long-term effects of poor periodontal health on cognition. Their findings, which show links between poor periodontal health and higher risks of dementia and cognitive decline, are consistent with our review's finding that periodontal disease is a major contributor to cognitive impairment. In addition to the more general findings from our umbrella review, their specificity—especially when stratifying the analysis by degree of tooth loss—offers a deeper understanding of how different impacts of periodontal deterioration on cognitive health might occur at different degrees of this deterioration. This major challenge is further highlighted by Asher et al.'s [26] critical evaluation of the quality of the evidence and reverse causality, which shows that even in this field, improved research methodologies were underplayed compared to what would be considered appropriate, necessitating significant improvement.

Skallevold et al. [34] expanded the talks to include a wider range of mental illnesses, such as dementia, where it would appear that oral health is related to each of the conditions listed. The consideration of our review of inflammatory pathways is consistent with the findings of Skallevold et al. [34], which emphasise systemic inflammation and microbial imbalance as underlying processes. In addition to supporting our demand for comprehensive dental care methods in dementia management, this larger viewpoint highlights the necessity for interdisciplinary approaches in addressing these disorders and supports the biological plausibility of the link between oral health and cognitive decline.

Our umbrella review did not particularly address the practical aspects of oral health care for older adults with dementia living in the community, but Ho et al. [37] did. Our findings about the increasing decline of oral health in dementia are consistent with their recognition of the dearth of accessible, specialised oral health care interventions and the limited services that are currently offered. In contrast to the theoretical connections offered in the preceding steps, the solutions developed by Ho et al. [37], such as the mobile dental programs and caregiver -supported oral hygiene, can be regarded as tangible manifestations of how oral health interventions could be put into practice.

4.1. Limitations

The primary difficulties of our umbrella review stem from attempting to compile results from multiple sources that use and approach diverse criteria. One of the main issues is the wide variation in the research that defines and quantifies mental decline and oral health. In this regard, it will be challenging to draw any firm conclusions about whether dental health and mental deterioration in demented patients are directly related, mostly due to the wide range of results that are not generally applicable. Furthermore, a large portion of the data we looked at was derived from observational studies, which frequently fail to take into consideration all the external factors that could have an impact on the results. These factors include disparities in affluence, access to healthcare, nutrition, and other health issues, among others [45-50]. These variables can have separate effects on mental and oral health, and if they are not consistently controlled for in research, it becomes more difficult to draw firm conclusions about causality. Furthermore, it can be challenging to determine if poor dental health causes a loss in mental performance or vice versa because some studies only record a single point in time [50-53].

The reliance on aggregate data obscures individual variances in the ways that dental health affects mental decline, which is another significant drawback. While some research suggests that maintaining proper dental hygiene may actually prevent mental decline, other research demonstrates a very strong correlation between poor oral health and a higher risk of mental decline [54-57]. This contradiction implies that the relationship between dental health and psychomotor function is influenced by individual characteristics, which could include predispositions or other lifestyle factors, a nuance that is sometimes obscured by the analysis of aggregate data from many groups.

4.2. Clinical Recommendations and Future Implications

Several useful suggestions are drawn from the results of our comprehensive analysis, which show a connection between the cognitive decline of dementia patients and their declining oral health. Above all, it is critical to incorporate thorough and frequent dental health examinations into the daily treatment of dementia patients. In addition to diagnosing and treating current dental disorders, these evaluations ought to emphasise preventative treatment in order to delay the development of future oral health difficulties.

Anti-inflammatory techniques should also be taken into account, given the evidence that suggests a possible inflammatory connection between poor dental health and cognitive impairment. This could entail localised or systemic therapies to lessen oral cavity inflammation. Additionally, adequate nutritional support—which includes foods that reduce inflammation—should be attained.

Individualised dental care regimens are necessary due to the wide range of ways that oral health affects cognitive performance. Given the patient's stage of dementia and general health, these strategies ought to be customised to meet their needs and capabilities. The maintenance of regular oral hygiene habits, which have been demonstrated to have preventive benefits against cognitive decline, should be part of care plans in addition to medical therapy for oral health issues.

Additionally, carers must receive training and education. In situations when the dementia patient may not be able to maintain good oral hygiene on their own, these carers should be equipped to offer information or guidance as needed. When assisting a patient with dental care, behavioural management skills must be part of the instruction given.

Furthermore, it is evident that more research is needed to understand the mechanisms and causal relationships behind the cognitive impairment associated with dental health in dementia. Standardised outcome measurements and methodologies should also be used in future research to lower variability and enhance finding comparison. In order to maintain cognitive health, such practices would aid in the development of more targeted therapies and suggestions for improved oral health.

CONCLUSION

Our research showed an association between poor oral health and deteriorating mental functions at all times. The data revealed that problems, such as periodontitis and tooth loss, were often associated with the risk of mental impairments. The literature review indicated that inflammation may be a common underlying factor for the relationship between deteriorating oral health and worsening brain health. Although there were some differences in the study approaches and their results, it was broadly agreed that good oral hygiene could help mitigate some decline of mental abilities in dementia sufferers. Since most of the studies we looked at were observational and differed in their approach, it is hard to tell whether one causes the other. Nonetheless, these findings highlight the importance of thorough oral care in managing dementia, suggesting that such care could be a practical way to lessen some mental decline.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

R.N.R., N.S.A., and S.B.: The conceptualization of the study was carried out; G.C.S., G.M., and D.R.: The methodology was designed; R.N.R. and N.S.A.: The software was curated; R.N.R. and S.B.: Formal analysis was conducted; R.N.R. and N.S.A.: The investigation was led; R.N.R. and N.S.A.: Data curation was also performed; D.R., M.M.M. and G.M.: The original draft preparation was done; G.C.S., G.M., and M.C.: Writing—review and editing conducted; G.C.S., M.C., and G.M.: Supervision was provided; G.M.: Funding acquisition was managed; D.R.: Administration was overseen. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| PECO | = Population, Exposure, Comparator, Outcome |

| PI | = Plaque Index |

| BOP | = Bleeding on Probing |

| PD | = Pocket Depth |

| CAL | = Clinical Attachment Loss |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.