All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Connecting the Dots: Mapping Reflections to Dental Public Health Competencies Through Thematic and Sentiment Analysis

Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to qualitatively analyze senior dental students’ reflections on community dental practice and map these reflections to the 10 Dental Public Health [DPH] competencies defined by the American Association of Public Health Dentistry.

Methods

This study included senior dental students at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, who participated in field visits as part of a community dental practice course. Students were instructed to write their reflections post-visit, which were then collected for analysis. In total, 144 reflections were analyzed using thematic and sentiment analyses, employing Python programming language and various libraries for data manipulation and analysis. The identified themes were then mapped onto DPH competencies.

Results

Thematic analysis revealed key themes at different levels of reflection, focusing on personal experiences, practical fieldwork, and broader perspectives on experiences. The analysis highlighted significant themes such as “pediatric dentistry,” “presentation,” “engagement,” and “passion.” Overall, sentiments were predominantly positive across all levels, with variations in emotional experiences among students. The mapping of these themes to DPH competencies showed a close alignment with several key competencies in dental public health.

Conclusion

This study provides insights into the educational experiences and emotional responses of dental students during community fieldwork. The alignment of students’ reflections with DPH competencies and the predominantly positive sentiments underscore the effectiveness of field experiences in fostering students’ professional and personal growth in dental public health.

1. INTRODUCTION

Dental public health is “the science and art of preventing and controlling dental diseases and promoting oral health through organized community efforts” [1]. In dental public health, disease prevention, dental health assessment, and oral health improvement are carried out at the population level rather than at the individual level.

In Saudi Arabia, only 0.41% of registered dentists specialize in dental public health [2]. This deficiency may affect the oral health status of the population, resulting in an increased incidence of dental diseases, especially in rural and suburban areas. Among dental students, interest in pursuing dental public health as a possible specialty can be developed during the undergraduate years. Students’ engagement in community-focused field trips, health promotion programs, and service-learning can help develop positive attitudes toward dental public health [3].

Service-learning integrates organized community services with coursework and curricula to meet specific community needs [4]. It helps students apply their knowledge and skills in meaningful opportunities to address community issues. It provides equal benefits to students and the community and focuses on both the service and learning processes.

Reflection is an integral part of service-learning. Toole and Toole defined reflection as “the use of creative and critical thinking skills to help prepare for, succeed in, and learn from the service experience, and to examine the larger picture and context in which the service occurs” [5]. Critical reflections allow students to: connect their experience to the coursework, leading to a deeper understanding of academic concepts applied in real life; analyze and assess their experiences, facilitating the development of critical thinking and problem-solving skills; increase self-awareness, empathy, and personal growth; engage in community issues and contribute to positive change by instilling a sense of civic responsibility; and enhance communication skills by enabling students to articulate their thoughts and feelings effectively, both verbally and in written form [4, 6, 7].

In dentistry, reflections on various service-learning projects have been explored. At the University of British Columbia, predoctoral dental students were asked to write down their reflections before, during, and after service-learning. The authors found that students not only described their experiences but also stated and analyzed their thoughts and feelings, evaluated their experiences, and suggested future actions and reassessment ideas. Reflections enhanced students’ learning experiences and community-based education and improved their attitudes toward the community and services [8]. Senior dental students at the University of Minnesota reflected on their community-based education program that serves patients with limited access to dental care. An analysis of the students’ reflections revealed three main themes: professional responsibility, willingness to volunteer, and the importance of oral health education [9]. However, reflecting on the predetermined assumptions and fears of a certain experiment and reporting whether this experience fulfills or challenges these assumptions can help educators address these expectations prior to the beginning of these experiences [10]. These learning reflections were never approached in a structured method for analysis. Also, there is no mention in the literature of theme mapping to the competencies of the practice of Dental Public Health.

2. METHODS

2.1. Field Visits and Reflections

Senior dental students at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, undertake a course in community dental practice, which requires them to participate in school field visits. During these visits, they examine and assess the oral health of school students, provide oral hygiene instructions, and teach them about dental problems and how to prevent them. Each dental student is instructed to reflect on their experiences after field visits. Each student was required to submit their reflection, but there were no right or wrong answers expected. The assignment focused solely on participation, not content evaluation, and students were explicitly encouraged to express their experiences openly and freely. The study was conducted with ethical approval from the King Abdulaziz University Ethics Committee, with exempt status granted due to the use of existing student reflections [Ethics Reference Number #245-11-23]. This research was conducted on humans by the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013 [http://ethics.iit.edu/ecodes/node/3931]. The sample included all 144 reflections from students in the senior cohort, with ages ranging from 22 to 23 years, and a balanced gender distribution of approximately 50% male and 50% female, as the entire cohort was included.

Reflection comprises three levels: Level 1 is self-reflection before the visit (expectations/mirror); Level 2 is the situation or setting during the visit (reality/ microscope); and Level 3 is the impact on the self and community (the big picture/binoculars). A list of questions for each level was given to dental students, and the instructors encouraged to use for each level, and the instructors encouraged dental students to use at least three questions at each level to guide their writing process.

2.2. Thematic Analysis

The authors conducted a thematic analysis to identify common themes in the reflections at each level. The data were segmented at a specified level and split into individual sentences using a custom simple sentence splitter. Key themes were identified based on sentence content. The themes reflected the students’ experiences, emotions, and insights related to their fieldwork.

2.3. Sentiment Analysis

The authors conducted sentiment analysis to assess the emotional tone of the students’ reflections. Each sentence in the reflection was analyzed using TextBlob to derive sentiment polarity scores (ranging from -1 to +1). Based on the polarity score, the sentiments were classified into three categories (positive, neutral, and negative). The average sentiment score for the students’ reflections at each level was calculated to provide personalized sentiment analysis.

2.4. Mapping to DPH Competencies

After identifying the themes, the authors matched each core theme to the 10 DPH competencies. This mapping aimed to contextualize students’ experiences and insights within the broader framework of dental public health education and practice.

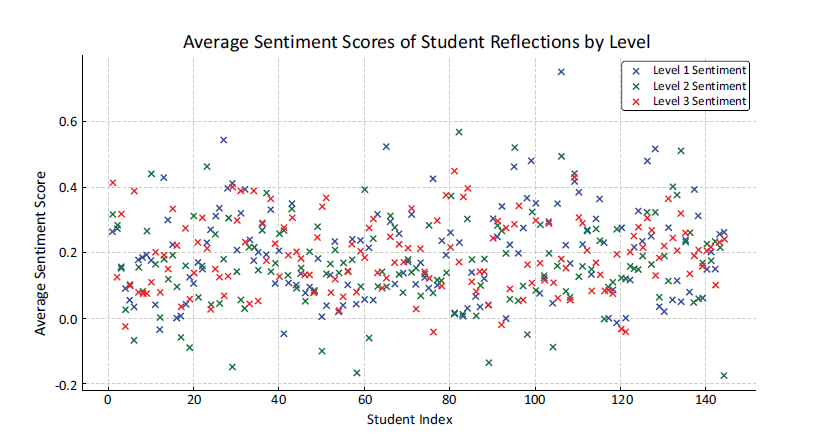

Study analyses were performed using Python programming language, using libraries such as pandas for data manipulation, TextBlob for sentimental analysis, and custom algorithms for thematic analysis. A scatter plot was used to visualize the average sentiment score for each student’s reflection using the matplotlib.pyplot and NumPy libraries. Word clouds were generated to visually represent the key themes identified in the thematic analysis using wordcloud library. The size of each word in the cloud corresponded to its frequency in the thematic analysis.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Thematic Analysis

Thematic analysis identified different themes for each of the three levels of reflection. Level 1 reflections were predominantly personal and focused on students’ experiences and emotions. The key themes are as follows: 1) presentation skills, for example, one student mentioned overcoming their dislike of presentations and motivating themselves to present with love; 2) pediatric patient interaction and developing patience, especially when managing a large group of children; and 3) a growing interest in pediatric dentistry (Table 1).

Level 2 reflections focused more on the practical aspects of fieldwork and the impact of individual experiences. The students discussed the logistics of their visits, including dividing tasks among team members and describing the settings in which they interacted with the children. Teamwork, organization, educational envi- ronment, and improvements in efficiency were among the most prominent themes (Table 1).

| Level | Themes Identified |

|---|---|

| Level 1 [Mirror] | Presentation Skills Pediatric Engagement Patient Interaction Passion for Pediatric Dentistry |

| Level 2 [Microscope] | Teamwork Organization Educational Environment Efficiency and Improvement |

| Level 3 [Binoculars] | Importance of Oral Health Education Career Considerations Gratitude and Enjoyment |

Students considered a broader perspective of their experiences when they reached Level 3. Common themes included: 1) the importance of oral health education; 2) career considerations, as these experiences led students to contemplate future specializations, such as becoming a pedodontist or engaging in public health; and 3) expressions of gratitude and enjoyment (Table 1).

The word cloud emphasized significant themes like “pediatric dentistry,” “presentation,” “engagement,” and “passion,” underlining the multifaceted nature of the students’ field experience (Fig. 1).

Word cloud generated based on the thematic analysis of the students’ reflections.

Scatter plot visualizes the average sentiment scores for each student’s reflections.

3.2. Sentiment Analysis

Overall, the sentiment analysis was positive across all three levels. There were fewer instances of neutral and negative sentiments at Levels 1 and 2, with a majority instead or predomenance of positive sentiments. Level 3 had the highest proportion of positive sentiments, suggesting a more favorable reflection on the broader aspects of fieldwork. In contrast, Level 2 had the highest proportion of negative sentiments (Table 2).

| Reflection Level | Positive Sentiments | Neutral Sentiments | Negative Sentiments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 (Mirror) | 439 | 189 | 74 |

| Level 2 (Microscope) | 460 | 212 | 109 |

| Level 3 (Binoculars) | 485 | 345 | 62 |

Individually, the students’ average sentiment scores varied across levels, indicating a diverse range of emotional experiences. While some students consistently expressed positive sentiments across all levels, others exhibited greater variations. Students who expressed negative sentiments were mainly concentrated at Level 2 (Fig. 2).

3.3. Mapping to Public Health Competencies

Mapping indicated that students’ field experiences and reflections closely aligned with several key competencies in dental public health. For instance, themes of organization and teamwork were aligned with competency in managing oral health programs, while reflections on ethical decision-making and patient interaction correlated with ethical practice in dental public health (Table 3).

4. DISCUSSION

This study aimed to qualitatively analyze dental students’ fieldwork reflections using thematic and senti- ment analyses. The analyses provided profound insights into their educational experiences and emotional responses and allowed for a comprehensive understanding of students’ learning and development in the context of dental education.

Personal and introspective themes identified at Level 1 align with the findings of Quick, who emphasized the importance of self- and peer assessment in developing skills in reflection, decision-making, professionalism, and communication, particularly in complex ethical scenarios [11]. Teamwork and organization were the highlights of Level 2, which reflects the essential role of inter- professional collaborative care and interprofessional education [IPE] in dental curricula, as discussed by Davis et al. [12]. Their study underlined the need for IPE to achieve patient-centered care, which resonates with the themes of teamwork and patient management found in the present analysis. The Interprofessional Education Collaborative published the Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice, comprising four categories: values/ethics, roles/responsibilities, interprofessional communication, and team and teamwork. These competencies offer educators a key framework for guiding the adoption and execution of IPE [13, 14].

| Dental Public Health Competency | Identified Themes from Student Reflections |

|---|---|

| Manage oral health programs for population health | Organization efficiency in field visits |

| Demonstrate ethical decision-making in the practice of dental public health | Ethical considerations in patient interaction |

| Evaluate systems of care that impact oral health | Observations of educational environment care systems |

| Design surveillance systems to measure oral health status and its determinants | Assessment of children’s oral health (foundational)* |

| Communicate on oral and public health issues | Presentations to children communication skills |

| Lead collaborations on oral and public health issues | Teamwork collaborative efforts |

| Advocate for public health policy, legislation, and regulations to protect and promote the public’s oral health, and overall health | Understanding of oral health importance of education |

| Critically appraise evidence to address oral health issues for individuals and populations | Critical self-reflection and evaluation (foundational)* |

| Conduct research to address oral and public health problems | Reflective practice (foundational)* |

| Integrate the social determinants of health into dental public health practice | Awareness of social determinants career considerations |

The predominantly positive sentiments across all levels reflect a positive learning environment in dental education, which is crucial for student satisfaction, psy- chological and social well-being, academic achievement, and modeling of dental students’ professional identity [15-17]. The presence of negative sentiments, especially at Level 2, which includes students’ experiences in the field, interacting with and examining children, aligns with the complexities of clinical training in dentistry and the switch from theory to implementation. The negative sentiments at Level 2 primarily stemmed from students’ initial experiences managing community field trips in a non-clinical setting. This shift required them to navigate logistical challenges, set up examination areas, and interact with children outside of a traditional clinical environment. As students encountered these real-world complexities for the first time, they experienced stress associated with organizing and adapting to the unstructured nature of community-based practice. This is similar to the transition from preclinical to clinical practice in dentistry, or the “dissonance” phase of learning, which involves a decrease in students’ self-confidence and motivation, and an increase in stress and uncertainty regarding their ability to perform well in the future [18].

Saudi Arabia’s cultural values, including an emphasis on community service and collective responsibility, likely influenced students’ reflections and learning experiences in dental public health. In Saudi dental education, there is a recognized need to integrate community health perspectives, which may inspire students to consider broader societal impacts on oral health, aligning with regional values of social responsibility and service [19,20]. This cultural framework provides depth to students' reflections on their roles in public health.

Mapping the themes to the 10 DPH competencies was an important aspect of this study. Although most themes directly represented competencies, some did not directly reflect specific competencies. For example, the compe- tency “Designing surveillance systems to measure oral health status and its determinants,” was not directly reflected in sample sentences; however, students’ engage- ment in assessing children’s oral health hints at foundational surveillance skills. Students’ self-reflection and evaluation of their experiences represent critical thinking essential for evidence appraisal, which aligns with the competency “Critically appraise evidence to address oral health issues for individuals and popu- lations.” Furthermore, although “Conducting research to address oral and public health problems” was not directly mentioned in the sample sentences, students’ reflective practice is a key research skill.

5. FUTURE DIRECTIONS AND LIMITATIONS

The present findings provide a foundation for future research, particularly for understanding the complex nature of dental students’ experiences in diverse cultural and educational settings. Although the analysis provided valuable insights, it was limited by its dependence on self-reported data that may contain inherent bias. Therefore, objective measures and longitudinal data analyses should be incorporated in future studies to better understand the evolution of student perceptions and skills over time.

CONCLUSION

This study contributes to the literature on dental education by thoroughly exploring dental students’ experiences, feelings, and sentiments during community fieldwork. The alignment of themes with dental public health competencies and the overall positive sentiments highlight the effectiveness of such field experiences in promoting students’ professional and personal growth.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

M.B., M.S.: Study conception and design; M.S.: Data collection; M.B., M.S.: Analysis and interpretation of results; M.B., M.S.: Draft manuscript preparation.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| IPE | = Interprofessional education |

| AAPHD | = American Association of Public Health Dentistry |

| DPH | = Dental Public Health |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study was approved by the King Abdulaziz University Ethics Committee Saudi Arabia, with exempt status granted as it involved secondary data analysis of anonymized reflections. The ethics reference number is #245-11-23.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

No specific consent was obtained from individuals, as the reflections were a regular course requirement and the project involved secondary data analysis of anonymized content. This approach was approved by the institutional review board.