All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Marginal Degradation of Universal Adhesive Restorations in NCCLs: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Abstract

Purpose

This systematic review aimed to answer the PICO question: do adhesive protocols used for non-carious cervical lesions (NCCLs) using a universal adhesive system influence marginal degradation, marginal staining, and retention of these restorations? The self-etching adhesive strategy and selective enamel etching were compared with the etch-and-rinse strategy as a control.

Materials and Methods

The study searched various databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Scopus, Embase, and grey literature, to find randomized clinical trials (RCTs) comparing self-etching (SE) or selective enamel etching (SEE) to the etch and rinse (ER) strategy. The risk of methodological bias was assessed using the Cochrane RoB 2 tool. Data were dichotomized and analyzed using RevMan v 5.3, adopting the Mantel-Haenszel method. The quality of evidence was assessed using Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE).

Results

Twenty RCTs were included in the meta-analysis. Results showed that using universal adhesives with the SE strategy resulted in clinical signs of marginal degradation at 12 months, 24 months, and 36 months of follow-up, and marginal staining at 24 months. The adhesive strategy did not interfere with the retention of restorative material used for NCCLs over 36 months, as assessed based on both the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) and World Dental Federation (FDI) criteria.

Conclusion

With moderate certainty of evidence, after 24 months of follow-up, the SE strategy results in the detection of clinical signs of marginal degradation and staining. The adhesive strategy adopted did not influence the retention rate of the restorations over 36 months of follow-up.

1. INTRODUCTION

Achieving a durable adhesive interface with enamel and dentin is an essential prerequisite to ensure the clinical success and longevity of adhesive dental restoration [1, 2]. To evaluate the effectiveness of this adhesion, tooth substrates have to be tested both in laboratory studies, under ideal working conditions, and in clinical trials that, when conducted appropriately, provide stronger scientific evidence [3, 4].

Non-carious cervical lesions (NCCLs) are considered most suitable for testing the clinical performance of direct adhesive restorations [5] due to the general absence of macro-mechanical retention [6, 7] and the presence of margins in both enamel and dentin. These margins are often sclerosed, which hinders adhesive effectiveness due to their acid-resistant characteristics [8, 9]. Variables such as marginal degradation, marginal staining and retention are the main parameters used to measure the clinical success of different adhesive strategies in these lesions [3].

Dental adhesives currently in use can be categorized into etching and rinse, self-etching, or selective enamel etching. In etch-and-rinse systems, the smear layer is removed by applying orthophosphoric acid at a concentration of 30-40%, which exposes the collagen [10]. The resin is then applied, infiltrating the dentinal tubules and interweaving with the collagen fibers, creating a base for the hybrid layer upon polymerization [11]. Self-etch adhesives, on the other hand, use acidic monomers capable of demineralizing and penetrating the dentin without the need for rinsing [12]. These adhesives alter the smear layer and integrate it into the hybrid layer. However, the effectiveness of self-etch adhesives when bonding to enamel remains uncertain. To address this concern, it is suggested that the enamel margins of the cavity be roughened with orthophosphoric acid before applying moderately self-etch adhesives (selective enamel etching) [13]. The most recent generation of adhesive systems is the universal or multi-mode systems [14]. This nomenclature refers to the possibility of using these systems in several protocols (etch and rinse (ER), self-etching (SE), or selective enamel etching (SEE)), and it is up to the dental surgeon to decide which one is best suited for each clinical situation [14, 15]. Since their launch, several randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have been conducted to evaluate the clinical performance of these systems. Some studies have reported that the adhesive protocol used does not affect the clinical performance of restorations fabricated for NCCLs, especially with regard to the retention of the restorative material [15, 16]. However, others have reported that small marginal failures were three times more frequent when a universal adhesive was applied in the SE mode [17], that the adhesive strategy used affects the marginal staining of restorations [18], and that the clinical performance of these systems was better when the ER strategy was adopted [19].

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to answer the following PICO question: can the adhesive protocols adopted in NCCLs restorations using a universal adhesive system influence the marginal degradation, marginal staining and retention of these restorations? The self-etching adhesive strategy and selective enamel etching were compared with the etch-and-rinse strategy as a control. Although meta-analyses with similar PICO questions have been published, they have presented contradictory results [20, 21]. This highlights the lack of consensus on the subject, which justifies the need for the present study. Moreover, the moderate certainty of evidence in the meta-analysis conducted by Uros et al. [21] suggests that future studies could have a significant impact and could alter the estimated effects.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Protocol and Registration

The study protocol was registered with the Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number: CRD42020200020) and adhered to the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) [22].

2.2. Search Strategy

On July 15, 2022, six databases—PubMed, Web of Science, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Scopus, Embase, and grey literature (OpenGrey)—were searched. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and keywords were utilized in the search strategies, which were adjusted accordingly for each database (Table 1). The search strategies were designed to find all relevant published articles without date restrictions or language. A supplementary manual search was also performed by reviewing the reference lists of the identified articles.

Eleven different universal adhesive systems were evaluated in the selected studies. The Single Bond Universal adhesive (3M ESPE) was employed in 13 studies [6-8, 16, 19, 29, 41, 42, 49, 51, 53, 55]. The other adhesives tested were Xeno Select (Dentsply) [45, 38], Prime&Bond Elect (Dentsply-Sirona) [29, 42, 45, 53], Gluma Bond Universal (Kulzer) [9], All Bond Universal (Bisco Dental) [9], Futurabond U (VOCO GmbH) [35-38, 46], Tetric N-Bond Universal (Ivoclar Vivadent) [44], Amber Universal (FGM) [43, 48], Adhese Universal (Ivoclar Vivadent) [40, 46, 47], Clearfil Universal Bond Quick (Kuraray Noritake) [50] and IBond Universal (Kulzer GmbH) [52].

The main restorative materials used were the Filtek Z350 XT (3M ESPE) composite resins [7, 8, 15, 16, 18, 19, 41, 49, 51, 55], Filtek Z250 (3M ESPE) [42], Evolux (Dentsply) [38, 45] Empress Direct (Ivoclar Vivadent) [44], Kalore (GC Corporation) [29, 53], Tetric EvoCeram (Ivoclar Vivadent) [37, 39, 40], Tetric N-Ceram (Ivoclar Vivadent) [43], Admira Fusion (Voco) [35-37, 47], Charisma Opal Flow (Haraeus-Kulzer) [6], Venus Diamond Flow (Kulzer GmbH) [52], G-aenial Universal Flo (GC Corporation) [6], Opalis (FGM) [48], and Liz (FGM) [43]. These were inserted in up to three increments. De Carvalho et al. [41] reported the layout sequence for each increment in the cavity.

| Database | Search strategy |

|---|---|

| PubMed | #1 (((((((((((((((((((Tooth Abrasion[MeSH Terms]) OR (Dental Abrasion[Title/Abstract])) OR (Tooth Erosion[MeSH Terms])) OR (Tooth Erosion*[Title/Abstract])) OR (Tooth Attrition[MeSH Terms])) OR (Dental Attrition[Title/Abstract])) OR (Occlusal Wear[Title/Abstract])) OR (Tooth Cervix[MeSH Terms])) OR (Cementoenamel Junction[Title/Abstract])) OR (Cervix Dentis[Title/Abstract])) OR (CEJ[Title/Abstract])) OR (Tooth Wear[MeSH Terms])) OR (Tooth Wears[Title/Abstract])) OR (Dental Wear[Title/Abstract])) OR (class V[Title/Abstract])) OR (class 5[Title/Abstract])) OR (non-carious cervical lesion[Title/Abstract])) OR (non-carious lesion[Title/Abstract])) OR (noncarious cervical[Title/Abstract])) OR (NCCL[Title/Abstract]) #2 ((((((((((Dentin-Bonding Agents[MeSH Terms]) OR (Acid Etching, Dental[MeSH Terms])) OR (Dental Etching[MeSH Terms])) OR (Universal adhesive[Title/Abstract])) OR (Adhesive System[Title/Abstract])) OR (Self adhesive[Title/Abstract])) OR (Self-adhesive[Title/Abstract])) OR (Self etch[Title/Abstract])) OR (Self-etch[Title/Abstract])) OR (Selective etch[Title/Abstract])) OR (Etching Modes[Title/Abstract]) #3 (((((Phosphoric Acids[MeSH Terms]) OR (Pyrophosphoric Acids[Title/Abstract])) OR (Universal adhesive[Title/Abstract])) OR (Etch-and-rinse[Title/Abstract]))) OR (Total etch[Title/Abstract]) #4 ((((((((((Dental Marginal Adaptation[MeSH Terms]) OR (Dental Marginal Adaptation*[Title/Abstract])) OR (Dental Restoration Failure[MeSH Terms])) OR (Dental Restoration Failure*[Title/Abstract])) OR (Dental Restoration Repair[MeSH Terms])) OR (Dental Restoration Repairs[Title/Abstract])) OR (Dentin Sensitivity[MeSH Terms])) OR (Dentin* Sensitivit*[Title/Abstract])) OR (Dentine Hypersensitivity[Title/Abstract])) OR (Tooth Sensitivit*[Title/Abstract])) OR (Dentin Hypersensitivity[Title/Abstract]) #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 |

| Web of Science | #1 TS=(Tooth AND Abrasion) OR TS=(Dental AND Abrasion) OR TS=(Tooth AND Erosion) OR TS=(Tooth AND Erosion*) OR TS=(Tooth AND Attrition) OR TS=(Dental AND Attrition) OR TS=(Occlusal AND Wear) OR TS=(Tooth AND Cervix) OR TS=(Cementoenamel AND Junction) OR TS=(Cervix AND Dentis) OR TS=(CEJ) OR TS=(Tooth AND Wear) OR TS=(Tooth AND Wears) OR TS=(Dental AND Wear) OR TS=(class AND V) OR TS=(class 5) OR TS=(non-carious AND cervical AND lesion) OR TS=(non-carious AND lesion) OR TS=(noncarious AND cervical) OR TS=(NCCL) #2 TS=(Dentin-Bonding AND Agents) OR TS=(Acid AND Etching, AND Dental) OR TS=(Dental AND Etching) OR TS=(Universal AND adhesive) OR TS=(Adhesive AND System) OR TS=(Self AND adhesive) OR TS=(Self-adhesive) OR TS=(Self AND etch) OR TS=(Self-etch) OR TS=(Selective AND etch) OR TS=(Etching AND Modes) #3 TS=(Phosphoric AND Acids) OR TS=(Pyrophosphoric AND Acids) OR TS=(Universal AND adhesive) OR TS=(Etch-and-rinse) OR TS=(Etch AND rise) OR TS=(Total AND etch) #4 TS=(Dental AND Marginal AND Adaptation) OR TS=(Dental AND Marginal) OR TS=(Dental Restoration Failure) OR TS=(Dental AND Restoration AND Failure*) OR TS=(Dental AND Restoration AND Repair) OR TS=(Dental AND Restoration AND Repairs) OR TS=(Dentin AND Sensitivity) OR TS=(Dentin* AND Sensitivit*) OR TS=(Dentine AND Hypersensitivity) OR TS=(Tooth AND Sensitivit*) OR TS=(Dentin AND Hypersensitivity) #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 |

| Cochrane | (Tooth Abrasion OR Dental Abrasion OR Tooth Erosion OR Tooth Erosion* OR Tooth Attrition OR Dental Attrition OR Occlusal Wear OR Tooth Cervix OR Cementoenamel Junction OR Cervix Dentis OR CEJ OR Tooth Wear OR Tooth Wears OR Dental Wear OR class V OR class 5 OR non-carious cervical lesion OR non-carious lesion OR noncarious cervical OR NCCL) in Title Abstract Keyword AND (Dentin-Bonding Agents OR Acid Etching, Dental OR Dental Etching OR Universal adhesive OR Adhesive System OR Self adhesive OR Self-adhesive OR Self etch OR Self-etch OR Selective etch OR Etching Modes) in Title Abstract Keyword AND (Phosphoric Acids OR Pyrophosphoric Acids OR Universal adhesive OR Etch-and-rinse OR Etch and rise OR Total etch) in Title Abstract Keyword AND (Dental Marginal Adaptation OR Dental Marginal Adaptation* OR Dental Restoration Failure OR Dental Restoration Failure* OR Dental Restoration Repair OR Dental Restoration Repairs OR Dentin Sensitivity OR Dentin* Sensitivit* OR Dentine Hypersensitivity OR Tooth Sensitivit* OR Dentin Hypersensitivity) in Title Abstract Keyword |

| Scopus | #1 (TITLE-ABS-KEY (tooth AND abrasion) OR TITLE-ABS KEY (dental AND abrasion) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (tooth AND erosion) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (tooth AND erosion*) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (tooth AND attrition) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (dental AND attrition) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (occlusal AND wear) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (cementoenamel AND junction) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (cervix AND dentis) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (cej) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (tooth AND wear) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (tooth AND wears) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (dental AND wear) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (class AND v) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (class 5) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (non-carious AND cervical AND lesion) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (non-carious AND lesion) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (noncarious AND cervical) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (nccl)) #2 (TITLE-ABS-KEY (dentin-bonding AND agents) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (acid AND etching, AND dental) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (dental AND etching) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (universal AND adhesive) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (adhesive AND system) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (self AND adhesive) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (self-adhesive) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (self AND etch) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (self-etch) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (selective AND etch) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (etching AND modes)) #3 (TITLE-ABS-KEY (phosphoric AND acids) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (pyrophosphoric AND acids) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (universal AND adhesive) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (etch-and-rinse) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (etch AND rise) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (total AND etch)) #4 (TITLE-ABS-KEY (dental AND marginal AND adaptation) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (dental AND marginal AND adaptation*) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (dental AND restoration AND failure) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (dental AND restoration AND failure*) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (dental AND restoration AND repair) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (dental AND restoration AND repairs) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (dentin AND sensitivity) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (dentin* AND sensitivit*) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (dentine AND hypersensitivity) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (tooth AND sensitivit*) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (dentin AND hypersensitivity)) #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 |

| OpenGrey | (Tooth Abrasion OR Dental Abrasion OR Tooth Erosion OR Tooth Erosion* OR Tooth Attrition OR Dental Attrition OR Occlusal Wear OR Tooth Cervix OR Cementoenamel Junction OR Cervix Dentis OR CEJ OR Tooth Wear OR Tooth Wears OR Dental Wear OR class V OR class 5 OR non-carious cervical lesion OR non-carious lesion OR noncarious cervical OR NCCL) AND (Dentin-Bonding Agents OR Acid Etching, Dental OR Dental Etching OR Universal adhesive OR Adhesive System OR Self adhesive OR Self-adhesive OR Self etch OR Self-etch OR Selective etch OR Etching Modes) AND (Phosphoric Acids OR Pyrophosphoric Acids OR Universal adhesive OR Etch-and-rinse OR Etch and rise OR Total etch) AND (Dental Marginal Adaptation OR Dental Marginal Adaptation* OR Dental Restoration Failure OR Dental Restoration Failure* OR Dental Restoration Repair OR Dental Restoration Repairs OR Dentin Sensitivity OR Dentin* Sensitivit* OR Dentine Hypersensitivity OR Tooth Sensitivit* OR Dentin Hypersensitivity) |

| Embase | Tooth abrasion':ti,ab,kw OR 'dental abrasion':ti,ab,kw OR 'tooth erosion':ti,ab,kw OR 'tooth erosion*':ti,ab,kw OR 'tooth attrition':ti,ab,kw OR 'dental attrition':ti,ab,kw OR 'occlusal wear':ti,ab,kw OR 'tooth cervix':ti,ab,kw OR 'cementoenamel junction':ti,ab,kw OR 'cervix dentis':ti,ab,kw OR cej:ti,ab,kw OR 'tooth wear':ti,ab,kw OR 'tooth wears':ti,ab,kw OR 'dental wear':ti,ab,kw OR 'class v':ti,ab,kw OR 'class 5':ti,ab,kw OR 'non-carious cervical lesion':ti,ab,kw OR 'non-carious lesion':ti,ab,kw OR 'noncarious cervical':ti,ab,kw OR nccl:ti,ab,kw) AND ('dentin-bonding agents':ti,ab,kw OR 'acid etching, dental':ti,ab,kw OR 'dental etching':ti,ab,kw OR 'universal adhesive':ti,ab,kw OR 'adhesive system':ti,ab,kw OR 'self adhesive':ti,ab,kw OR 'self etch':ti,ab,kw OR 'selective etch':ti,ab,kw OR 'etching modes':ti,ab,kw) AND (('phosphoric acids':ti,ab,kw OR 'pyrophosphoric acids':ti,ab,kw OR 'universal adhesive':ti,ab,kw OR 'etch and rinse':ti,ab,kw OR etch:ti,ab,kw) AND rise:ti,ab,kw OR 'total etch':ti,ab,kw) |

2.3. Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection Process

Two researchers (EPV and TAFB) independently selected the titles and abstracts of the studies identified by searching the electronic databases and exported the data to EndNote (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, USA). Duplicate studies were subsequently eliminated through a two-step process. Initially, EndNote software was employed to eliminate duplicates; however, due to variations in database indexing processes, this tool cannot eliminate all duplicates. Therefore, in the second step, articles were sorted alphabetically by title, and duplicate studies were identified and removed manually. Any differences of opinion among the researchers were resolved through discussion and consensus; if necessary, a third researcher (CMSS) was consulted. For studies that seemed to meet the exclusion criteria or lacked sufficient data in the title and abstract, the full-text article was obtained and reviewed to make a decision.

Inclusion criteria were established based on the following PICO strategy [23].

2.3.1. Patients

Adult patients presenting with NCCLs and with an indication for direct composite restoration. Lesions were required to be non-carious, non-retentive, more than 1 mm deep, involve both the enamel and dentin of vital, non-mobile teeth, and have the cavosurface margins involving not more than 50% of the enamel.

2.3.2. Intervention

Composite resin restorations performed using universal adhesive through selective enamel conditioning or self-etching adhesive strategies.

2.3.3. Comparison

Composite resin restorations performed using a universal adhesive through etch and rinse adhesive strategy.

2.3.4. Outcomes

Clinical signs of marginal degradation were considered as primary endpoints. Marginal staining and retention of the restoration as the secondary endpoints. Clinical assessments were based on the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) criteria and/or the World Dental Federation (FDI) criteria.

Only RCTs were considered. The reference lists of the RCTs that met all the inclusion criteria and were considered potentially relevant for this review were manually searched. Two researchers (EPV and TAFB) independently tracked all the references from these RCTs.

2.4. Risk of Bias

The full texts of articles that met the eligibility criteria were comprehensively and independently evaluated by two researchers (EPV and TAFB) for methodological bias risk using the Cochrane RoB 2 tool [24]. Disagreements were settled through discussion, with the involvement of a third researcher (CMSS) when required.

The overall risk of bias was rated as low, unclear, or high based on six key domains: bias arising from the randomization process; bias due to deviations from intended interventions; bias due to missing outcome data; bias in measurement of the outcome; bias in selection of the reported result; and overall. For all studies classified as “unclear” in a key domain, the authors of the article in question were contacted for additional information.

2.5. Data Overview

Two independent researchers (EPV and TAFB) extracted relevant study data from the eligible articles. Disagreements were resolved through discussion, and a third researcher (CMSS) was consulted when necessary.

Information about the author, year of publication, sample size, age of participants, study design, adhesive strategies used, commercial name and manufacturer of the universal adhesives, statistical analyses, follow-up period, and results regarding retention, marginal degradation and marginal staining were tabulated. In instances where data was missing, efforts were made to contact the corresponding author via email weekly for up to four weeks to obtain the necessary information.

2.6. Summary Measures and Summary of Results

The studies were categorized based on the criteria used for conducting the clinical assessments. The data collected were dichotomized (retention/non-retention, marginal degradation/no degradation, and marginal staining/no marginal staining) and analyzed using RevMan v 5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration; Copenhagen, Denmark) by adopting the Mantel-Haenszel method, a random effects model, and with the risk difference as the effect measure.

Meta-analyses were performed for the variables retention, marginal degradation, and marginal staining to compare the adhesive strategies self-etching (SE) vs. etching and rinsing (ER) and selective enamel etching (SEE) vs. ER at different follow-up time points.

2.7. Grading the Certainty of Evidence

The certainty of evidence (certainty in effect estimates) was assessed by two independent reviewers (TAFB and EVT) for the outcomes (retention, marginal degradation and marginal stating) using the GRADE classification. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or consensus involving a third-party reviewer (AMS). The GRADE approach initially assumes that the included studies provide high-quality evidence. However, if serious or very serious problems related to the risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, or publication bias are identified, the quality or certainty of the evidence is reduced accordingly to moderate, low, or very low [25, 26].

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study Selection

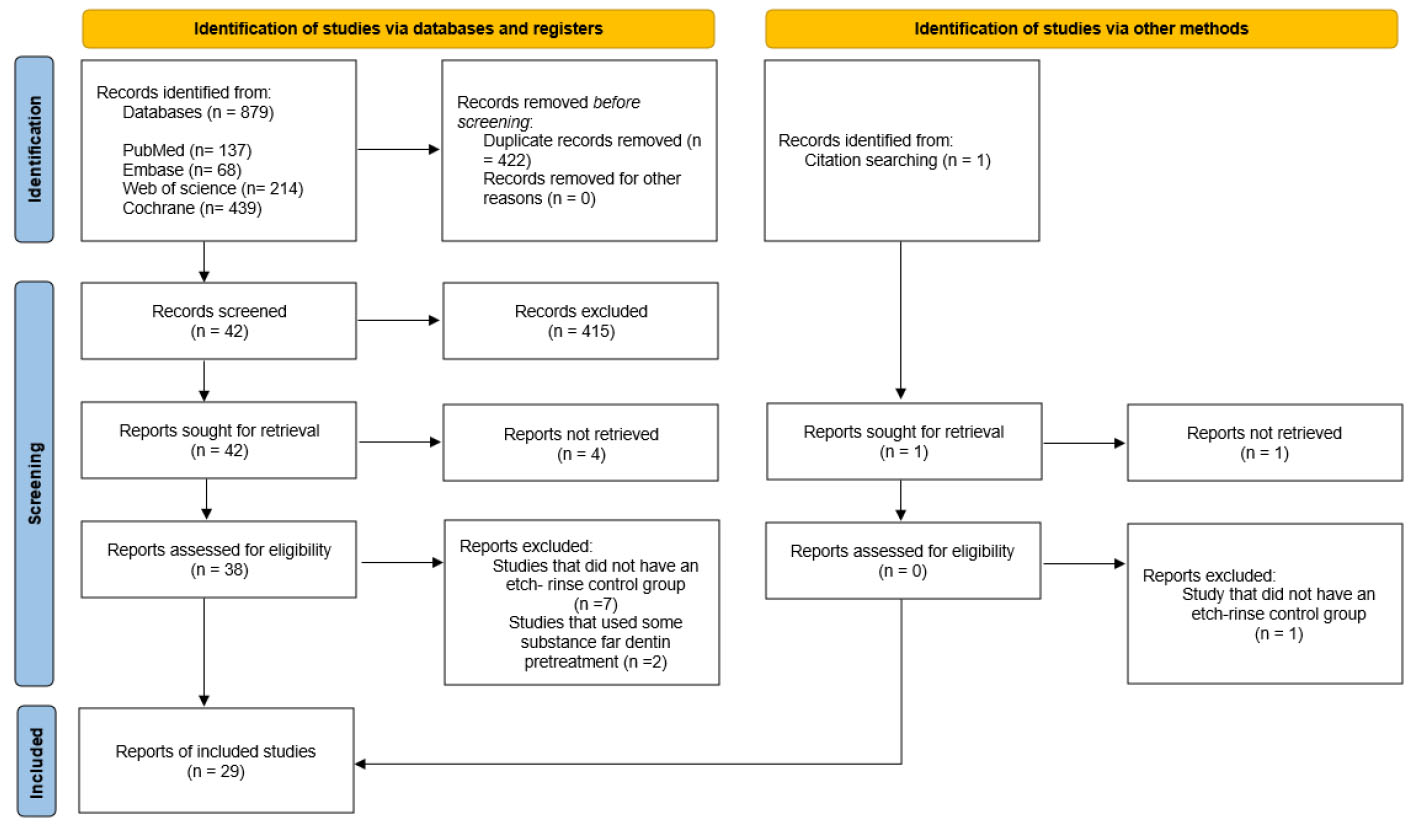

The initial search across all databases yielded 879 records. Out of these, 422 duplicate studies were eliminated using EndNote. Another 415 studies were removed after evaluation based on their titles and abstracts. Forty-two studies of interest were thoroughly read and analyzed in full-text form, and out of these, 29 met the pre-established inclusion criteria.

Among the articles excluded at this stage, seven did not adopt the conditioning and washing strategy [17, 27-31], which was adopted as a comparison parameter for study eligibility; the dentin was saturated with 100% ethanol prior to the application of the adhesive system in one study [32-34]; and the dentin was pre-treated with an enzyme inhibitor (epigallocatechin-3-gallate) in another study [34]. Fig. (1) summarizes the article selection process according to the PRISMA statement.

3.2. Characterization of the Included Studies

The studies were characterized according to a pre-established data extraction protocol. A total of 800 participants were included in the studies (20–63 participants per study), and participant ages ranged from 20 to 84 years. In total, 3,621 NCCLs were restored (100–246 per study). The number of NCCLs ranged from 1 to 8 per participant. Twenty-one studies reported that the experimental design followed the established Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines [7, 8, 15, 16, 35-51]. Fifteen studies reported registering the clinical trial with the German Clinical Trials Register [52], ClinicalTrials.gov [35-37, 44, 46, 47, 50], or ReBEC [16, 38, 42, 43, 45, 48, 49]. Eighteen studies featured the paired design [6, 7, 16, 18, 19, 35-41, 44, 45, 48, 49].

The morphological characterization of the NCCLs was described in detail in 18 studies [19, 35-38, 41-45, 48, 49, 51, 29, 53]; this included information on their dimensions (cervical-incisal height, width, and depth) and the geometry (45°, 45-90°, 90-135°, >135o.) and degree of sclerosis according to the criteria described by Swift et al. [54]. Two studies [9, 50] reported the dimensions and

Flowchart of the study selection process as recommended by the PRISMA statement (2020).

geometry of the NCCLs selected for sampling but did not report the degree of sclerosis present in them. Two studies [46, 47] described only the geometry and degree of sclerosis, while two others [8, 52] described only the depth of the lesions. Five studies did not describe any type of morphological characteristics of the NCCLs other than those that were part of the inclusion criteria [6, 18, 39, 40, 55].

The number of operators varied from study to study. In 12 studies, a single operator was responsible for performing all the restorations [8, 9, 29, 39, 40, 49, 50, 52, 55]. In the others, there were 2-5 operators who went through a calibration process. No operator was blinded to the adhesive strategies employed in any of the clinical trials, as each strategy required specific clinical procedures.

Twenty-five clinical trials described performing pumice and water prophylaxis immediately [6, 11, 12, 14, 19, 20, 23, 24, 31-33, 36, 40, 42, 56, 39-41, 43, 46, 47, 50, 52], one week [9], or two weeks [15, 16, 35-38, 44, 45, 49] before the restorative procedure. Only De Carvalho [41], Oz et al. [9], Cruz et al. [40], Hass et al. [43], and Barceleiro et al. [38] reported that the participants received guidance on oral hygiene.

Sixteen clinical trials employed absolute isolation of the operative field for humidity control during the restorative procedure [15, 35-40, 42-45, 48, 49, 51]. Twelve trials used relative isolation techniques, such as the use of cotton rollers, retractor wire, and saliva suction [7-9, 19, 41, 56, 46, 47, 50, 52, 53]. One clinical trial described no humidity control procedure [6].

The mechanical treatment of the substrate also varied among the studies. Some trials did not prepare, roughen, or create any retention features on the enamel or dentin of the NCCL-affected teeth [15, 16, 38, 40, 42, 43, 45-49, 51]. Others employed hyper-mineralization of dentin by aspirating [29, 44, 53, 55] and/or creating bevels at the occlusal margin of the lesion [8, 18, 52, 55].

The USPHS or FDI criteria were used for the clinical evaluation of the restorations placed. The clinical follow-up periods ranged from 6 to 60 months. The main data extracted from the studies are summarized in Table 2.

|

Study (Country, Year) |

No. of Groups |

Adhesive Strategy (n per group) |

NCCL Preparation | Universal Adhesive (manufacturer) | Follow Up | Evaluation Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mena-Serrano et al. (Brazil/USA, 2012) |

4 | ER Moist Dentin (50) ER Dry Dentin (50) SE (50) SEE (50) |

None | Single Bond Universal (3M ESPE) |

6 months | USPHS |

| Perdigão et al. (Brazil/USA) 2014) |

18 months | USPHS | ||||

| Loguercio et al. (Brazil/ USA), 2015) |

36 months | USPHS | ||||

| Matos et al. (Brazil/ USA), 2020 |

60 months | USPHS FDI |

||||

| De Carvalho et al. (Brazil, 2015) |

4 | ER (38) SE (38) ER- Smokers (38) SE- No Smokers (38) |

Not described | Single Bond Universal (3M ESPE) |

12 months | USPHS |

| Lawson et al. (USA, 2015) |

3 | SU-ER (42) SU-SE (42) |

0.5mm bevel on the occlusal margin | Single Bond Universal (3M ESPE) |

24 months | USPHS |

| *SBM-ER (42) | * Scotchbond™ Multipurpose – Step 3 (3M ESPE) |

|||||

| Lopes et al. (Brazil, 2016) |

4 | ER Moist Dentin (31) ER Dry Dentin (31) SE (31) SEE (31) |

None | XenoSelect, (Dentsply) | 6 months | FDI |

| Barceleiro et al. (Brazil, 2022) |

36 months | USPHS FDI |

||||

| Albuquerque et al (Brazil, 2017) |

4 | ER Moist Dentin (50) ER Dry Dentin (50) SE (50) SEE (50) |

Not described | Futurabond U (VOCO) |

6 months | FDI |

| Albuquerque et al (Brazil, 2020) Albuquerque et al (Brazil, 2022) |

- | - | - | - | 18 months | USPHS FDI |

| - | - | - | - | 36 months | USPHS FDI |

|

| Islatince et al (Türkiye, 2018) |

3 | ER (82) SE (86) SEE (78) |

Dentin roughening Bevel on enamel |

Single Bond Universal (3M ESPE) |

18 months | FDI |

| Loguercio et al (Brazil/ Chile, 2018) |

4 | SU-ER (48) SU-SE (48) SU-ER + DR (48) SU-SE + DR (48) |

Dentin roughening – DR (Half of NCCL) |

Tetric N-Bond Universal (Ivoclar-Vivadent) |

18 months | USPHS FDI |

| Ruschel et al (Brazil/ USA, 2018) |

4 | SU-ER (52) SU-SE (50) |

Dentin roughening | Single Bond Universal (3M ESPE) Prime & Bond Elect (Dentsply Sirona) |

18 months | USPHS |

| Rushel et al (Brazil/ USA, 2019) |

PBE-ER (50) PBE-SE (51) |

36 months | USPHS | |||

| Matos et al (Brazil, 2019) |

4 | ER (54) SE (54) |

None | Ambar Universal (FGM) |

18 months | USPHS modificado FDI |

| ER + Cu (54) SE + Cu (54) |

Ambar Universal (FGM) + Nanoparticulas de Cu |

|||||

| Oz et al (Türkiye, 2019) |

7 | G-ER (21) G-SE (20) G-SEE (22) |

Not described | Gluma Universal (Kulzer) |

24 months | USPHS |

| A-ER (20) A-SE (21) A-SEE (22) |

All Bond Universal (Bisco) |

|||||

| **SB2-ER (29) | **Single Bond 2 (3M ESPE) |

|||||

| Zanatta et al (Brazil, 2019) |

4 | SU-ER (38) SU-SE (38) SB2 (38) CLF (38) |

None | Single Bond Universal (3M ESPE) Single Bond 2 (3M ESPE) Clearfill SE Bond (Kuraray Noritake Dental Inc.) |

24 months | FDI |

| Atalay et al (Türkiye, 2019) |

3 | ER (55) SE (55) SEE (55) |

0.5mm bevel (Occlusal margin) |

Single Bond Universal (3M ESPE) |

36 months | USPHS |

| Manarte-Monteiro (Portugal, 2019) |

6 | FBU-ER (35) FBU-SE (35) AD-ER (35) AD-SE (35) ***FBDC-SE (35) ***FBDC- SEE (35) |

None | Futurabond U (VOCO) Adhese Universal (Ivoclar Vivadent) ***FuturaBond DC |

12 months | FDI |

| Manarte-Monteiro (Portugal, 2022) |

- | - | - | - | 24 months | FDI |

| Cruz et al (Portugal, 2020) |

2 | ER (59) SE (58) |

None | Tetric N-Bond Universal (Ivoclar-Vivadent) |

6 months | FDI |

| Cruz et al (Portugal, 2021) |

- | - | - | Adhese Universal (Ivoclar-Vivadent) |

24 months | FDI |

| Kemaloglu et al (Türkiye, 2020) |

4 | ER + Charisma Opal Flow (25) SE + Charisma Opal Flow (25) ER + G-aenial Opal Flo (25) SE + G-aenial Opal Flo (25) |

Not described | Single Bond Universal (3M ESPE) |

24 months | USPHS |

| Perdigão et al (Spain/ USA, 2020) |

4 | SU-ER (34) SU-SE (35) |

Not described | Single Bond Universal (3M ESPE) |

36 months | USPHS |

| SU-ER + SBM* (34) SU-SE + SBM* (31) |

* Scotchbond™ Multiuso – Passo 3 (3M ESPE) |

|||||

| Hass et al (Brazil/ Chile, 2021) |

4 | ER+10s polymerization (35) ER+40s polymerization (35) SE+10s polymerization (35) SE+40s polymerization (35) |

None | Ambar Universal (FGM) |

18 months | FDI |

| Follak et al (Brazil, 2021) |

4 | PB-ER (53) PB-SE (50) SBU-ER (54) SBU-SE (54) |

None | Prime&Bond Elect (Dentsply Sirona) Single Bond Universal (3M ESPE) |

6 months | FDI USPHS |

| Merle et al (Germany, 2022) |

4 | iBond -ER (50) iBond-SE (50) iBond-SEE (29) ****OFL-ER (50) |

Enamel and dentin roughening | iBond Universal (Kulzer GmbH) ****OptiBond FL (Kerr GmbH) |

12 months | FDI |

| Oz et al (Türkiye, 2022) |

5 | CUQ-ER (47) CUQ-SE (46) CUQ-SEE (47) C-SE (47) TNU-ER (47) |

Not described | Clearfil Universal Bond Quick (Kuraray Noritake) Clearfil SE Bond (Kuraray Noritake) Tetric N-Bond Universal (Ivoclar Vivadent) |

24 months | USPHS |

Summary of risk of bias of included studies.

3.3. Analysis of the Risk of Bias in the Studies

Upon evaluating the predefined key domains to assess the risk of bias for each article, it was noted that none of the RCTs had implemented operator blinding. While the absence of operator blinding in RCTs indicates a significant risk of bias in this domain, we acknowledge that blinding might not have been feasible due to variations in clinical protocols for each restorative procedure. Evaluations for the other domains are detailed in Fig. (2).

3.4. Meta-analysis

3.4.1. Marginal Degradation

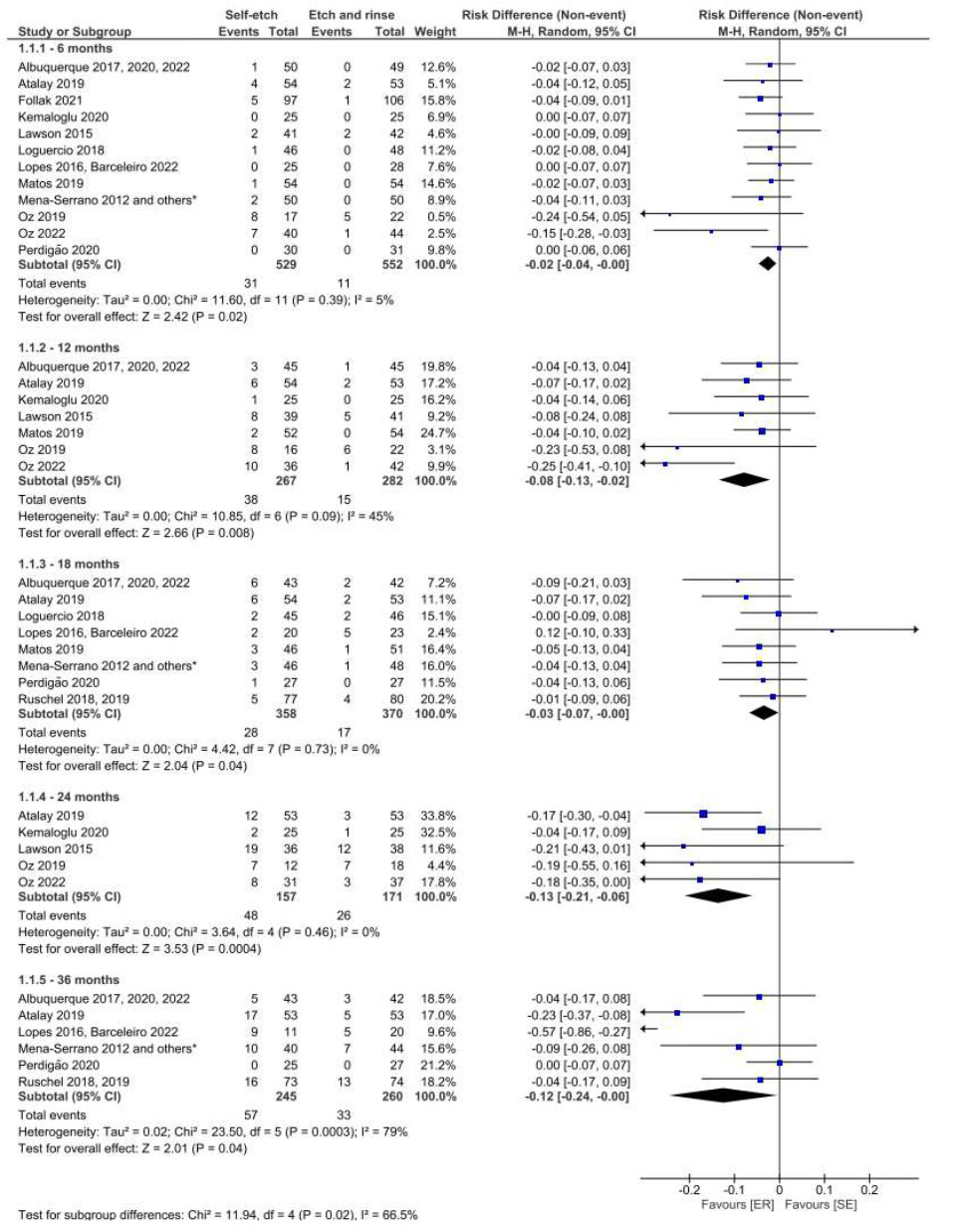

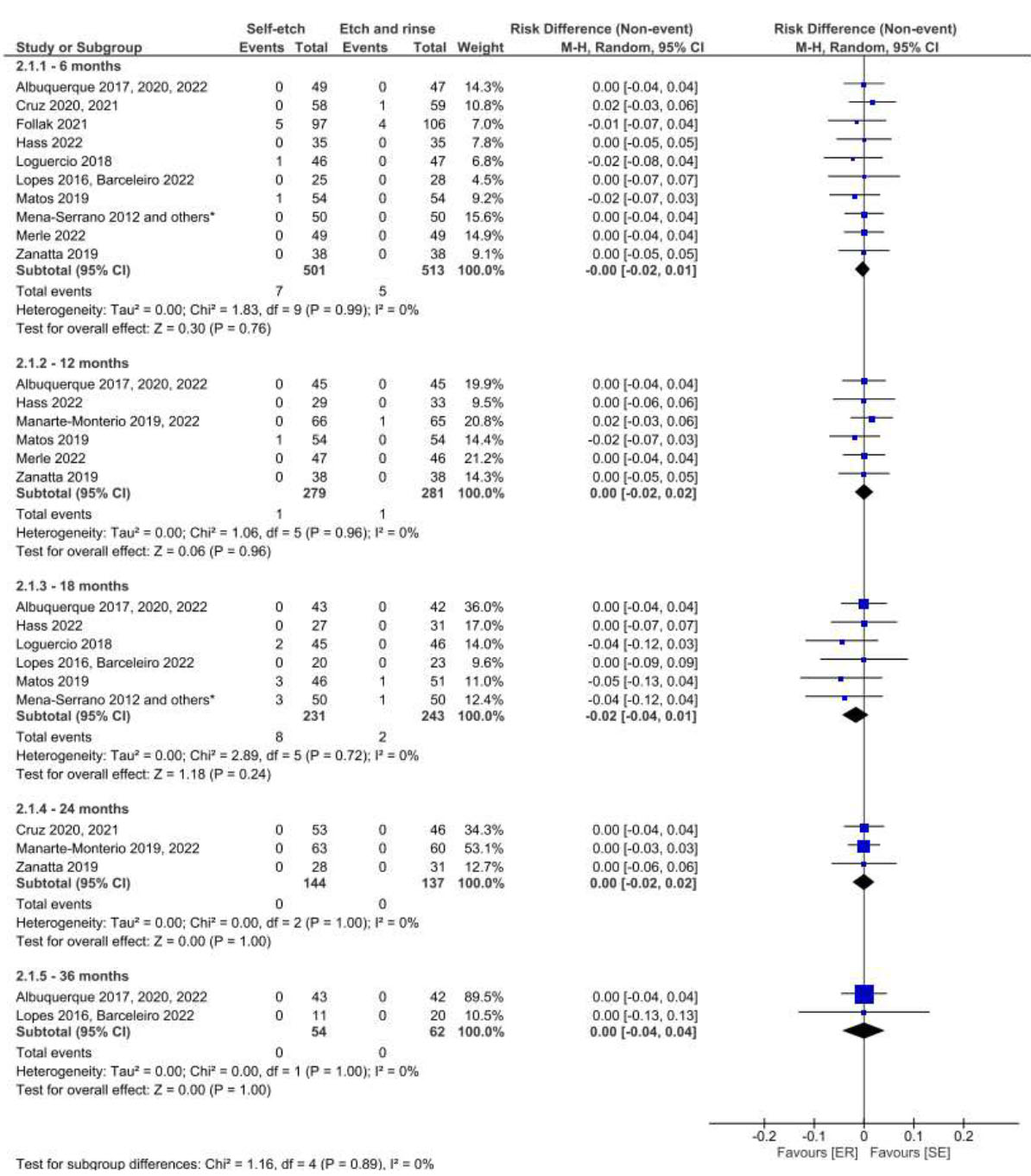

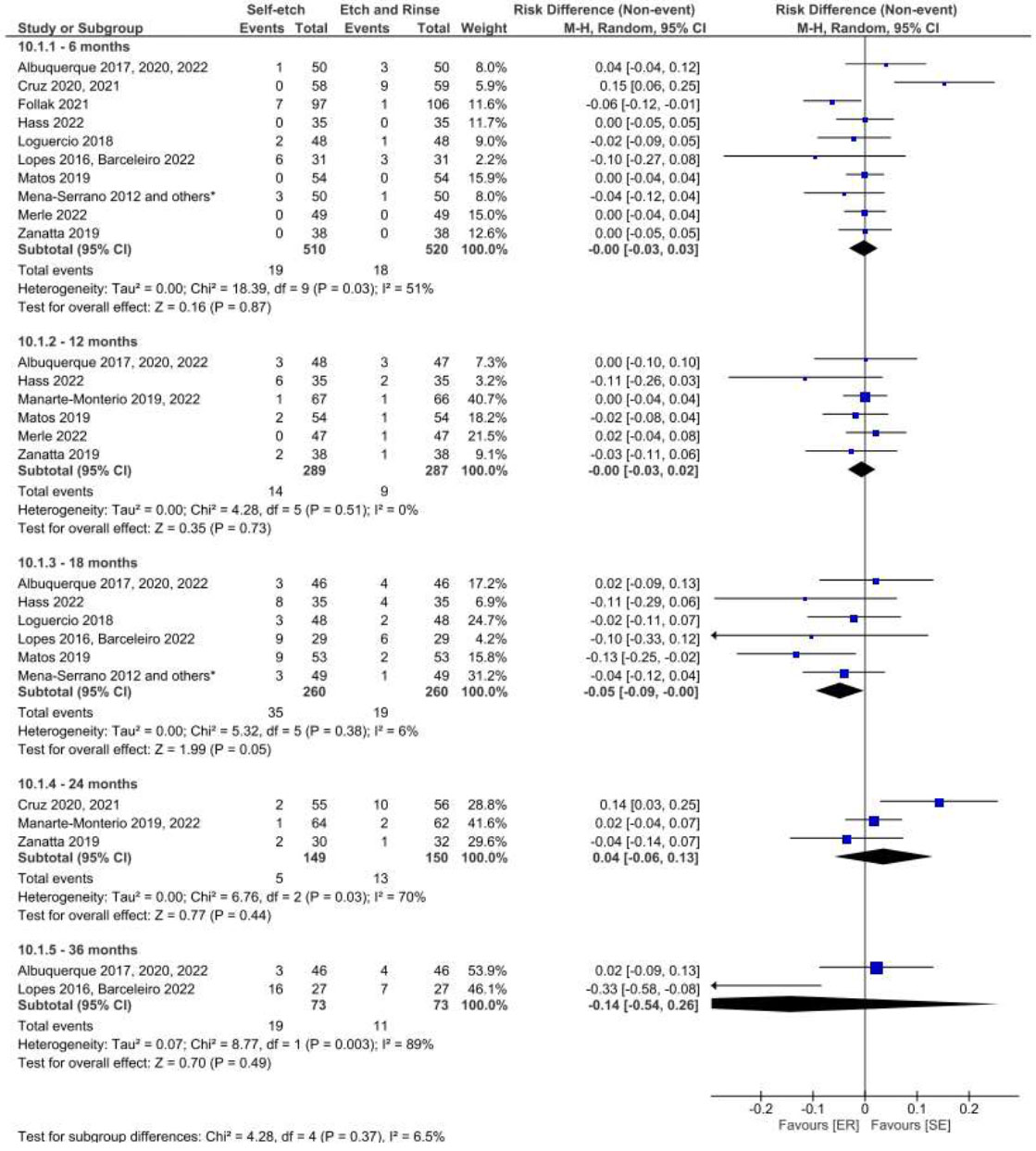

Figs. (3 and 4) illustrate the results of the meta-analysis for the comparison of the SE and ER strategies. When using the USPHS criterion, the use of universal adhesives with the SE strategy resulted in the detection of clinical signs of marginal degradation at 12, 24, and 36 months of follow-up (Fig. 3). However, at 36 months, the collected data was characterized by high heterogeneity (I2= 79%). When the FDI criteria were employed for evaluation, there was no difference in this regard between these strategies in the same follow-up period (Fig. 4).

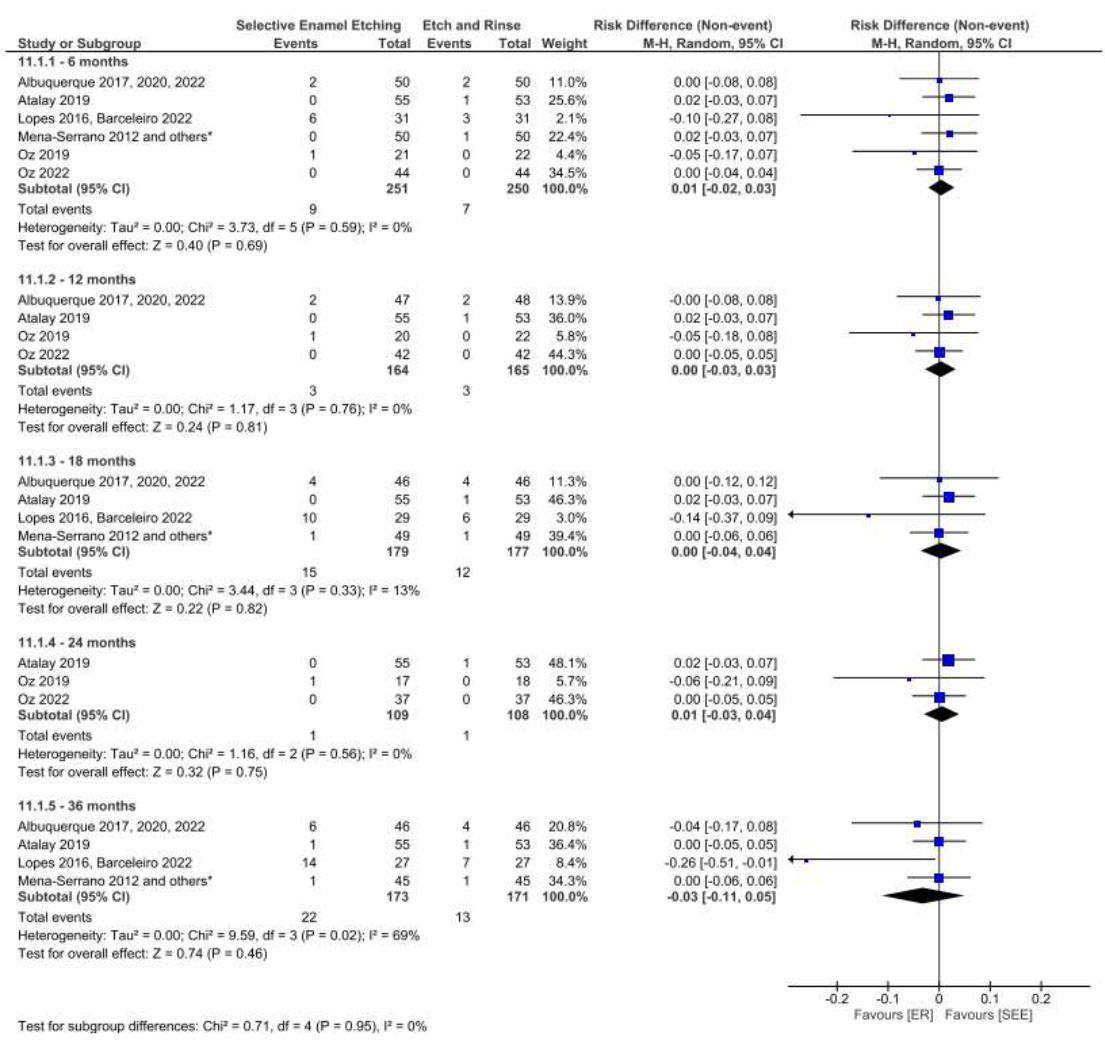

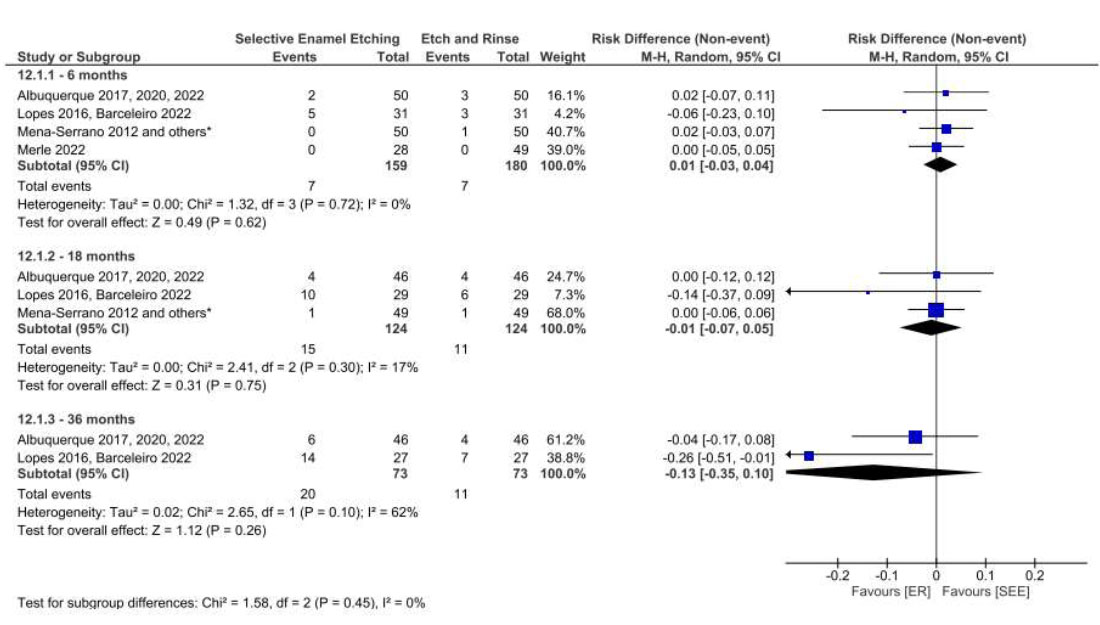

There was no statistically significant difference between the SEE and ER strategies at 6, 12, 18, 24, and 36 months based on the USPHS criteria and at 6, 18, and 36 months based on the FDI criteria, as illustrated in Figs. (5 and 6), respectively.

Forest plot of the marginal degradation in the SE vs. ER strategies. Follow-ups 6, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months for USPHS criteria.

Forest plot of the marginal degradation in the SE vs. ER strategies. Follow-ups 6, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months for FDI criteria.

3.4.2. Marginal Staining

Fig. (5) illustrates the results of the meta-analysis for the comparison of the SE and ER strategies. Employing the SE strategy resulted in the detection of clinical signs of marginal staining at 24 months of follow-up (Fig. 7) with low data heterogeneity (I2=0%). When the FDI criteria were employed for evaluation, there was no difference in this regard between these strategies in the same follow-up period (Fig. 8).

Forest plot of the marginal degradation in the SEE vs. ER strategies. Follow-ups 6, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months for USPHS criteria.

There was no statistically significant difference between the SEE and ER strategies at 6, 12, 18, 24, and 36 months based on the USPHS criteria (Fig. 9), as well as at 6, 18, and 36 months based on the FDI criteria (Fig. 10).

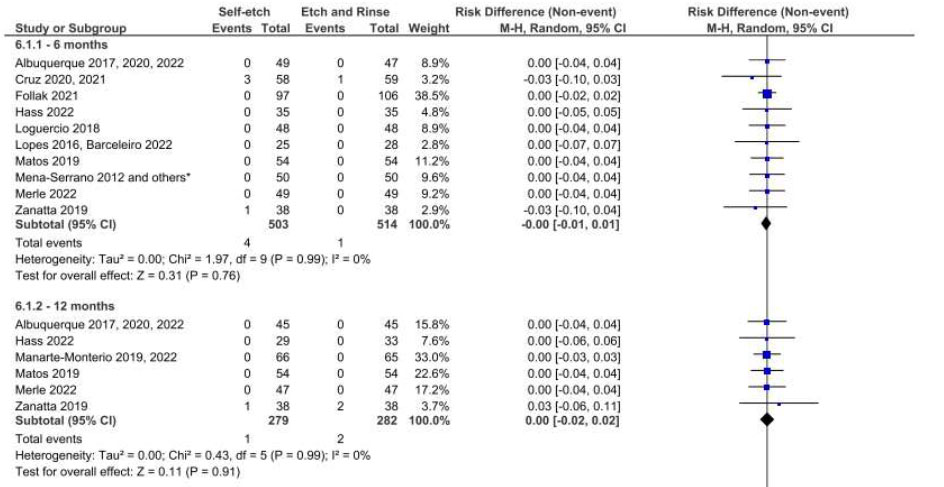

3.4.3. Retention

The adhesive strategy adopted (ER, SE, or SEE) did not interfere with the retention of the restorative material in NCCLs over 36 months of clinical follow-up when a universal adhesive was used (Figs. 11, 12, 13 and 14) based on both the USPHS and FDI criteria.

Forest plot of the marginal degradation in the SEE vs. ER strategies. Follow-ups 6, 18 and 36 for FDI criteria.

Forest plot of the marginal staining in the SE vs. ER strategies. Follow-ups 6, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months for USPHS criteria.

Forest plot of the marginal staining in the SE vs. ER strategies. Follow-ups 6, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months for FDI criteria.

Forest plot of the marginal staining in the SEE vs. ER strategies. Follow-ups 6, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months for USPHS criteria.

Forest plot of the marginal staining in the SE vs. ER strategies. Follow-ups 6, 18 and 36 months for FDI criteria.

Forest plot of the retention in the SE vs. ER strategies. Follow-ups 6, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months for USPHS criteria.

Forest plot of the retention in the SE vs. ER strategies. Follow-ups 6, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months for FDI criteria.

Forest plot of the retention in the SEE vs. ER strategies. Follow-ups 6, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months for USPHS criteria.

3.5. Certainty of Evidence

3.5.2. Marginal Degradation and Marginal Staining - SE vs. ER Groups

Although a moderate certainty of evidence was observed for the marginal degradation data at the 12- and 24-month clinical follow-up when the USPHS criteria were adopted, the certainty was very low at 36 months. The certainty of evidence regarding marginal staining data at 24 months was moderate. When the FDI criteria were adopted, the certainty of evidence was moderate for marginal degradation only at 12 months of clinical evaluation. For the other evaluation periods, the certainty of evidence was low for both degradation and marginal staining (Table 3).

Forest plot of the retention in the SEE vs. ER strategies. Follow-ups 6, 18 and 36 months for FDI criteria.

| Criteria | Outcomes/Follow-up |

No. of Participants (studies)/Follow-up |

Certainty of the Evidence (GRADE) |

Relative Effect (95% CI) |

Anticipated Absolute Effects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk with Etch-and-rinse | Risk Difference with Self-etch | |||||

| U S P H S |

Marginal degradation /12 months | 549 (7 RCTs) |

Moderatea |

RR 0.05 (0.01 to 0.10) | 53 per 1.000 | 51 fewer per 1.000 (53 fewer to 48 fewer) |

| Marginal degradation /24 months | 328 (5 RCTs) |

Moderatea |

RR 0.130 (0.040 to 0.022) | 152 per 1.000 | 132 fewer per 1.000 (149 fewer to 146 fewer) | |

| Marginal degradation /36 months | 505 (6 RCTs) |

Very lowa,b,c |

RR 0.08 (-0.04 to 0.20) | 127 per 1.000 | 117 fewer per 1.000 (132 fewer to 102 fewer) | |

| Marginal staining /24 months | 328 (5 RCTs) |

Moderatea |

RR 0.12 (0.03 to 0.21) | 129 per 1.000 | 113 fewer per 1.000 (125 fewer to 102 fewer) | |

| F D I |

Marginal degradation /12 months | 560 (6 RCTs) |

Moderatea |

RR 0.05 (0.01 to 0.10) | 4 per 1.000 | 3 fewer per 1.000 (4 fewer to 3 fewer) |

| Marginal degradation /24 months | 281 (3 RCTs) |

Lowa,c |

RR 0.130 (0.040 to 0.022) | 0 per 1.000 | 0 fewer per 1.000 (0 fewer to 0 fewer) | |

| Marginal degradation /36 months | 116 (2 RCTs) |

Lowa,b,d |

RR 0.08 (-0.04 to 0.20) | 0 per 1.000 | 0 fewer per 1.000 (0 fewer to 0 fewer) | |

| Marginal staining /24 months | 280 (3 RCTs) |

Lowa,c |

RR 0.12 (0.03 to 0.21) | 58 per 1.000 | 51 fewer per 1.000 (57 fewer to 46 fewer) | |

a Most studies are at unclear risk of bias.

b The confidence interval does not exclude great benefit or great harm, resulting in imprecision.

c Imprecise estimates.

d High and non-explained heterogeneity.

| Criteria | Outcomes/Follow-up |

No. of Participants (studies)/Follow-up |

Certainty of the Evidence (GRADE) |

Relative Effect (95% CI) |

Anticipated Absolute Effects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk with Etch-and-rinse | Risk Difference with Self-etch | |||||

| U S P H S |

Marginal degradation /6 months | 489 (6 RCTs) |

Lowa,b |

RR -0.01 (-0.04 to 0.02) | 33 per 1.000 | 33 fewer per 1.000 (34 fewer to 32 fewer) |

| Marginal degradation /18 months | 335 (4 RCTs) |

Very lowa,b,c |

RR -0.01 (-0.07 to 0.06) | 48 per 1.000 | 48 fewer per 1.000 (51 fewer to 45 fewer) | |

| Marginal degradation /36 months | 310 (4 RCTs) |

Lowa,d |

RR -0.06 (-0.14 to 0.01) | 126 per 1.000 | 133 fewer per 1.000 (143 fewer to 125 fewer) | |

| Marginal degradation /6 months | 487 (6 RCTs) |

Lowa,b |

RR -0.01 (-0.04 to 0.02) | 33 per 1.000 | 33 fewer per 1.000 (34 fewer to 32 fewer) | |

| Marginal degradation /18 months | 332 (4 RCTs) |

Lowa,b |

RR 0.01 (-0.03 to 0.06) | 36 per 1.000 | 36 fewer per 1.000 (37 fewer to 34 fewer) | |

| Marginal staining /36 months | 310 (4 RCTs) |

Very lowa,b,d |

RR 0.00 (-0.08 to 0.08) | 75 per 1.000 | 75 fewer per 1.000 (82 fewer to 69 fewer) | |

| F D I |

Marginal degradation /6 months | 328 (4 RCTs) |

Lowa,b |

RR -0.01 (-0.04 to 0.02) | 0 per 1.000 | 0 fewer per 1.000 (0 fewer to 0 fewer) |

| Marginal degradation /18 months | 228 (3 RCTs) |

Lowa,b,c |

RR -0.01 (-0.07 to 0.06) | 9 per 1.000 | 9 fewer per 1.000 (9 fewer to 8 fewer) | |

| Marginal degradation /36 months | 113 (2 RCTs) |

Lowa,b,c |

RR -0.06 (-0.14 to 0.01) | 0 per 1.000 | 0 fewer per 1.000 (0 fewer to 0 fewer) | |

| Marginal staining /6 months | 326 (4 RCTs) |

Lowa,b |

RR -0.01 (-0.04 to 0.02) | 0 per 1.000 | 0 fewer per 1.000 (0 fewer to 0 fewer) | |

| Marginal staining /18 months | 228 (3 RCTs) |

Moderatea,b |

RR 0.01 (-0.03 to 0.06) | 0 per 1.000 | 0 fewer per 1.000 (0 fewer to 0 fewer) | |

| Marginal staining /36 months | 118 (2 RCTs) |

Lowa,b,d |

RR 0.00 (-0.08 to 0.08) | 0 per 1.000 | 0 fewer per 1.000 (0 fewer to 0 fewer) | |

a Most studies are at unclear risk of bias.

b The confidence interval does not exclude great benefit or great harm, resulting in imprecision.

c Imprecise estimates.

d High and non-explained heterogeneity.

3.5.3. Marginal Degradation and Marginal Staining - SEE vs. ER Groups

The certainty of the evidence was low or very low for all clinical evaluation periods when the SEE and ER strategies were compared for the degradation /marginal staining outcomes based on the USPHS criteria. Based on the FDI criteria, the certainty of evidence was moderate at 18 months for the marginal staining outcome and low for the other follow-up periods, both for degradation and marginal staining (Table 4).

3.5.4. Retention

When clinical evaluation was performed using the USPHS criteria, the certainty of evidence ranged from low to very low for all the different follow-up periods. When the FDI criteria were used, the certainty of evidence for the SE vs. ER comparison at 18 months, as well as the SEE vs. ER comparison at 6 and 18 months, was moderate. For the other periods, the certainty of the evidence was low or very low. Table 5 summarizes the data for the different follow-up periods.

4. DISCUSSION

An increasing amount of research is being conducted to evaluate the clinical efficacy of universal adhesive systems. Generally, RCTs are conducted to assess clinical performance, with the retention of the restorative material being the main parameter used to evaluate longevity. Nevertheless, parameters such as marginal degradation and marginal staining are also crucial indicators for assessing the clinical success of adhesive procedures in NCCL restorations, despite the subjective nature of the evaluation criteria used (such as the USPHS and FDI criteria), which can result in considerable variability among evaluators [56].

| Criteria | Strategy | Outcomes/Follow-up |

No. of Participants (studies) |

Certainty of the Evidence (GRADE) |

Relative effect (95% CI) |

Anticipated Absolute Effects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk with Etch-and-rinse | Risk Difference with Self-etch | ||||||

|

U S P H S |

SE vs ER | Retention/6 months | 1101 (12 RCTs) |

Lowa,b |

RR 0.01 (-0.01 to 0.03) | 13 per 1.000 | 12 fewer per 1.000 (13 fewer to 12 fewer) |

| Retention/12 months | 565 (7 RCTs) |

Lowa,b |

RR 0.03 (-0.01 to 0.07) | 11 per 1.000 | 10 fewer per 1.000 (11 fewer to 10 fewer) | ||

| Retention/18 months | 771 (8 RCTs) |

Lowa,d |

RR 0.02 (0.00 to 0.05) | 39 per 1.000 | 38 fewer per 1.000 (39 fewer to 37 fewer) | ||

| Retention/24 months | 337 (5 RCTs) |

Very lowa,b,e |

RR 0.04 (-0.02 to 0.10) | 0 per 1.000 | 0 fewer per 1.000 (0 fewer to 0 fewer) | ||

| Retention/36 months | 546 (6 RCTs) |

Very lowa,b,e |

RR 0.05 (-0.01 to 0.10) | 48 per 1.000 | 45 fewer per 1.000 (48 fewer to 43 fewer) | ||

| SEE vs ER | Retention/6 months | 501 (6 RCTs) |

Lowa,b |

RR -0.01 (-0.05 to 0.02) | 28 per 1.000 | 28 fewer per 1.000 (29 fewer to 27 fewer) | |

| Retention/18 months | 356 (4 RCTs) |

Lowa,b |

RR -0.01 (-0.05 to 0.02) | 68 per 1.000 | 68 fewer per 1.000 (71 fewer to 66 fewer) | ||

| Retention/36 months | 344 (4 RCTs) |

Very lowa,d |

RR 0.00 (-0.04 to 0.04) | 76 per 1.000 | 76 fewer per 1.000 (79 fewer to 73 fewer) | ||

|

F D I |

SE vs ER | Retention/6 months | 1030 (10 RCTs) |

Very lowa,b,e |

RR 0.01 (-0.01 to 0.03) | 35 per 1.000 | 34 fewer per 1.000 (35 fewer to 34 fewer) |

| Retention/12 months | 576 (6 RCTs) |

Lowa,b |

RR 0.03 (-0.01 to 0.07) | 31 per 1.000 | 30 fewer per 1.000 (32 fewer to 29 fewer) | ||

| Retention/18 months | 520 (6 RCTs) |

Moderatea,c |

RR 0.02 (0.00 to 0.05) | 73 per 1.000 | 72 fewer per 1.000 (73 fewer to 69 fewer) | ||

| Retention/24 months | 299 (3 RCTs) |

Very lowa,b,e |

RR 0.04 (-0.02 to 0.10) | 87 per 1.000 | 83 fewer per 1.000(88 fewer to 78 fewer) | ||

| Retention/36 months | 146 (2 RCTs) |

Lowa,b,e Lowa,b,e

|

RR 0.05 (-0.01 to 0.10) | 151 per 1.000 | 143 fewer per 1.000 (152 fewer to 136 fewer) | ||

| SEE vs ER | Retention/ 6 months | 339 (4 RCTs) |

Moderatea,b Moderatea,b

|

RR -0.01 (-0.05 to 0.02) | 39 per 1.000 | 39 fewer per 1.000 (41 fewer to 38 fewer) | |

| Retention/ 18 months | 248 (3 RCTs) |

Moderatea,b Moderatea,b

|

RR -0.01 (-0.05 to 0.02) | 121 per 1.000 | 122 fewer per 1.000 (127 fewer to 119 fewer) | ||

| Retention/ 36 months | 146 (2 RCTs) |

Lowa,d,e Lowa,d,e

|

RR 0.00 (-0.04 to 0.04) | 151 per 1.000 | 151 fewer per 1.000 (157 fewer to 145 fewer) | ||

a Most studies are at unclear risk of bias.

b The confidence interval does not exclude great benefit or great harm, resulting in imprecision.

c Imprecise estimates.

d High and non-explained heterogeneity.

e Moderate and non-explained heterogeneity.

Previously published systematic reviews have pointed out that when the substrate is dentin, the adhesive performance is largely pH-dependent [57, 58]. When an adhesive with a mild pH was used on dentin, the ER and SE adhesive strategies were found to be comparable [57]. However, the use of universal adhesives with intermediate strong pH resulted in a reduction in adhesive strength after aging, regardless of the substrate or adhesive strategy used [57]. These findings directed the authors of this meta-analysis to perform a sensitivity analysis for the study by Oz et al. [9]. They chose to exclude data from groups that used the GLUMA® Bond Universal adhesive system (Kulzer; pH 1.6–1.8, intermediate strong), and considered only the data from the All Bond Universal adhesive (Bisco Dental; pH, 3.2), which resulted in the data becoming more homogeneous.

The quantitative analysis in the present study shows that the SE application mode influences marginal degradation and staining when compared to the ER strategy. Moreover, the results of the meta-analysis indicate that the use of the SE adhesive strategy, as evaluated based on the USPHS clinical evaluation criteria, leads to clinical signs of marginal degradation at 12 and 24 months (moderate quality of evidence for both periods). At the 36-month follow-up, the ER strategy appeared to be superior to the SE strategy but with very low quality of evidence, which limits the confidence of the effect. Furthermore, these findings were not confirmed when the same comparison and follow-up periods were evaluated using the FDI criteria. Considering that both the USPHS and FDI criteria have been validated for assessing the clinical performance of restorations, this disagreement may be due to the difference in the number of studies that adopted these criteria (7 vs. 6 at 12 months; 5 vs. 3 at 24 months; and 6 vs. 2 at 36 months).

When marginal staining was the endpoint evaluated, the results of the meta-analysis showed that the ER strategy performed better than the SE strategy at 24 months of clinical follow-up, with moderate quality of evidence. Again, the same finding was not confirmed when the FDI criteria were employed. Despite the findings related to marginal degradation /staining, the adhesive strategy used (ER, SE, or SEE) did not have an impact on the retention of the restorative materials over 36 months based on both criteria. However, this result should be interpreted with some caution, since the quality of evidence was very low for this effect.

Our findings were contrary to those of the study by Arbildo et al. [59], where both the ER and SE strategies resulted in good adaptation and no marginal staining, but better retention results were observed when a universal adhesive was applied using the ER strategy. However, the authors combined data from clinical evaluations using both criteria (USPHS and FDI), as well as from different observation periods, in the same meta-analysis. Moreover, no tools for determining the quality of evidence were used.

More recently, Uros et al. [21] reported that the ER strategy showed better retention of restorations compared to the SE strategy at 12 months, but this difference was not observed after a longer period of clinical observation (36 months). However, the quality of evidence for the latter follow-up period was low. Fitting and marginal staining showed similar clinical characteristics for the comparison between the ER and SE strategies. In this study, separate meta-analyses were conducted for different clinical observation periods, although different clinical evaluation criteria (USPHS and FDI) were considered within each meta-analysis.

Dreweck et al. [60] conducted a network meta-analysis of 66 RCTs and concluded that none of the adhesive strategies compared showed superior clinical performance with regard to retention. A limitation of comparing this result with those of the present meta-analysis is that the previous study considered several types of adhesive systems, not just universal ones. However, the authors did raise a relevant point: the data related to clinical evaluation were grouped based on the evaluation period, as described in our methodology. As it is expected that the failure rates of these restorations will tend to increase over the course of the clinical evaluation period, combining this data may result in the findings differing from the actual results.

A significant finding of this study was the notably high rates of marginal discoloration in restorations using universal adhesives in SE strategy. This was linked to the lower bonding effectiveness of self-etch adhesives on unetched enamel compared to etched enamel. NCCLs often involve sclerotic dentin, which can hinder optimal adhesion due to its resistance to acid [8, 9]. The self-etch mode might not be the best choice for surfaces that are highly sclerotic. Despite the drawbacks of ER, such as technical sensitivity and multiple steps, it tends to be more reliable than SE. Clinical studies have shown that SE results in higher rates of marginal discoloration than the ER strategy, which adversely affects the aesthetic outcome of restorations. Selective enamel etching appears to be a viable option to avoid acid etching of dentin without interfering with the clinical performance of restorations.

A limitation of this study is the high heterogeneity of some analyses due to high risk of bias and lack of information in some selected studies. More studies need to be conducted over longer evaluation periods before a more informed opinion can be provided regarding the results.

CONCLUSION

With moderate certainty of evidence, after 24 months of follow-up, the SE strategy results in the detection of clinical signs of marginal degradation and staining. However, at 36 months, these signs are only detectable with regard to marginal degradation, with very low certainty of evidence. Moreover, the adhesive strategy adopted (ER, SE, or SEE) does not influence the retention rate of restorations over 36 months of follow-up, although the quality of evidence in this regard ranged from low to very low.

CLINICAL RELEVANCE

The use of universal adhesive systems with the ER or SEE strategy promotes more predictable marginal degradation/staining results over longer periods of clinical observation.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

T.B., E.T., A.S., C.A., C.S.: Study conception and design; CS.:Data collection.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| NCCLs | = Non-carious cervical lesions |

| RCTs | = Randomized clinical trials |

| SE | = Self-etching |

| USPHS | = United States Public Health Service |