All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

The Correlation between Dental Health Status and Educational Level, Age, and Gender as Demographic Attributes of the Children of Migrant Workers

Abstract

Introduction

Migrant workers and their families appear to have greater health issues, given their need to adjust to new environments and restricted access to healthcare services. One obstacle to receiving healthcare is culture. This study aims to analyze the correlation between dental health status and the level of class, age, and gender as demographic attributes in the children of migrant workers.

Methods

This cross-sectional study involved the children of Indonesian migrant workers who resided in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The population of the study consisted of children who met the inclusion criteria. Their ages varied between six and twelve. In this study, we used the purposive sampling method. There are 93 samples that met the inclusion criteria. We obtained the data on dental health status using the RedCap online form, which is used in the WHO oral health survey. The researchers performed data analysis, the def-t and DMF-T measurement index and prevalence analyses, and the Spearman-Rho correlation tests to examine the data and determine the appropriate analytical tests.

Results

The characteristics of the children of Indonesian migrant workers are as follows: based on the class level, 1, 5, and 6; based on age, 6-8 and 9-11; and based on gender, nearly equal between the male and female respondents. The DMF-T index score was 1.22, and the def-t index was 3.77 among the migrant children. The prevalence of caries in permanent adult crowns was lower (53.76%) than that in primary children crowns (64.52%.). Root caries is present in less than 1% of the adult population; however, its prevalence among the children of migrant workers is indeterminable. The majority of the negative correlation occurs between the level of grade and age of the children of Indonesian migrant workers and their dental and oral health status; however, there is no significant correlation between gender and oral health status.

Conclusion

The DMF-T index of migrant children is low, while their def-t index is high. The prevalence of crown and root caries among the children of migrant workers is significantly higher. There are many negative correlations between the educational level and age of the migrant children and their oral health status.

1. INTRODUCTION

Dental caries has significant implications for children’s health [1, 2] and has become the primary public health issue [3, 4]. Researchers have addressed the negative effects of dental caries on children’s well-being, life quality [1, 5], and health in general [1] Numerous studies have found a correlation between chronically impaired oral health and systematic conditions that may arise in the later stages of life [1].

The health of migrant workers and their families has become an important public health issue [6]. Migrant workers do not receive sufficient healthcare and social support due to their extended time in the host countries [6]. Therefore, it is essential to design health programs [7] to help them survive and improve their quality of life. Migrant workers are more likely to have health issues because they have to adjust to new environments and have limited access to healthcare facilities [8]. Culture is one obstacle that could prevent workers and their families from receiving health services is culture [9]. A literature review has given evidence regarding the obstacles to healthcare services among migrant workers, including language, interest in alternative therapy, unawareness, public stigma, and poor treatment by healthcare providers [7].

As members of the labour force, migrant workers may be a more vulnerable group because they are foreigners who are working in inadequate workplace environments with low salaries, poor interpersonal and community ties, limited seeking health care behaviours, and instances of discrimination regarding their independent assessment of oral health [6]. Policy implementation plays a crucial role in helping them overcome the obstacles [7, 8].

Oral health is one of the most significant unfulfilled health requirements among migrant worker’s children, and a significant number of them lack even the most basic oral health knowledge [10]. Various factors may contribute to the development of dental caries and oral health issues among migrant workers [4, 11]. A comprehensive under- standing of safety factors, critical functions in cultural interactions, and diverse ethnic communities within the healthcare system can promote an improved outcome for high-risk populations [9, 11].

The primary obstacles that prevent children of migrant workers from receiving health treatment in general and oral health care, in particular, include lack of transportation, insurance, sick leave, threat of wage loss or employment termination, language barriers, insufficient regular dentists, and limited clinic hours [10, 12]. In addition, many migrant workers do not understand the basic aspects of oral health, including the correlation between sweetened food and dental caries, the benefits of fluoride, and the positive impact of maintaining good oral hygiene on general health [10].

Studies on the aforementioned issues among workers are abundant; however, the ones examining the use of healthcare services by Indonesian migrant workers are limited [13]. Other studies related to migrant workers in different countries discover that their limited access to healthcare services is due to several factors, including the healthcare system, language barriers, and a lack of knowledge regarding their healthcare and insurance rights [6, 10].

Caries in dentine is a major oral disease that not only causes discomfort and infection but also affects producti- vity [14]. Severe dental caries may lead to tooth loss, which will negatively affect the aesthetic values, function, self-esteem, and quality of life of an individual [14]. Early diagnosis of caries lesions can certainly help physicians or dentists formulate the most effective treatments. The absence of consistency among contemporary criterion systems for diagnosing carious lesions impedes the comparability of the results assessed in epidemiologic and clinical studies [15].

The production of acid, which results from the decomposition of sugar, initiates progressive tooth decay. However, many other factors may affect the development of tooth decay and the level of severity, including society, family, and individuals. Individual demographic character- istics, such as age, education level, and gender, influence the incidence and severity of caries [16].

Information concerning the key risk factors associated with chronic diseases is the main input for health authorities in planning health promotion and primary prevention programs [17]. Based on standardized survey instruments and previously agreed indicators, definitions, methods, and sampling principles, the WHO has developed a new instrument for diagnosing chronic diseases and several risk factors relevant to oral health and dental health status [17]. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to analyse the correlation between dental health status and educational level, age, and gender as demographic attributes of the children of migrant workers. The hypothesis of the research is that there is a correlation between dental health status and educational level, age, and gender as demographic attributes of the children of migrant workers.

2. METHODS

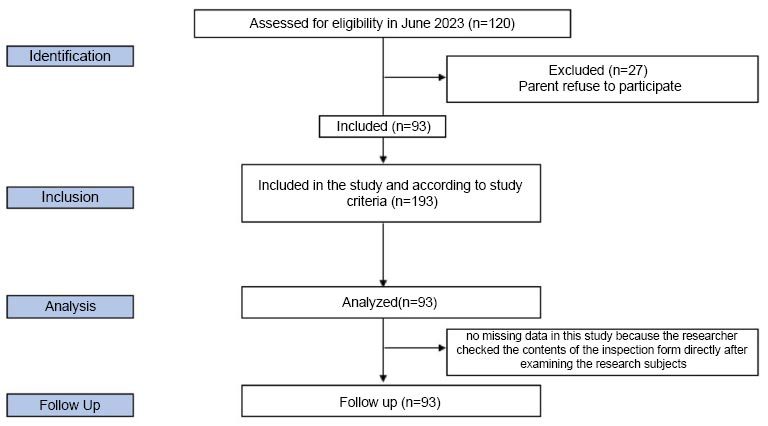

The study design applied a cross-sectional method, in which the researchers collected the data using the online research form [18]. The population of the study consisted of the children of Indonesian migrant workers who lived in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, aged 6-12 years, who met the specified inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria included students in grades 1, 5, and 6 who were in great health and had been granted permission to participate in the study. The children who were unable to complete the stages of the study and did not have special needs were excluded. This study used a purposive sampling technique, and the correlation formula was applied to a specific sample size. Among 120 sample populations, 93 samples met the inclusion criteria. Twenty-seven samples did not get permission from their parents. The strobe flow diagram is described in Fig. (1).

STROBE flow diagram.

This study involved students in grades 1, 5, and 6. We involved the students of grade 1, with children aged 5 years. It is important because it relates to the development of caries levels in primary teeth, which could potentially show changes over a shorter period of time [17]. The reason for selecting 12 years of age in grades 5 and 6 is because it is a crucial age for children to leave primary school, provides a reliable sample, and is easily accessible through the school system. In addition, at this age, all permanent teeth have erupted except the third molar; thus, it could be considered a global indicator age group for international comparisons and monitoring disease trends [17].

The study variables were the crown and root dental health status, and the demographic attributes included educational level, age, and gender. Table 1 displays the definition of the variables.

The data on carious lesions and dental health status was collected using a RedCap online form. Dental health status was collected through a WHO oral health survey [17]. The WHO oral health survey uses the RedCap online form, which we used to collect data on dental health status.

Prior to the study, the respondents’ guardians or parents had accepted and approved the informed consent. We calibrated the results of the dental health status examination using the Kappa Test, which was used to assess caries, resulting in a value of 0.80, which was categorized as a strong agreement.

| Variables | Operational Definitions | Tools and Measurement Methods | Measuring Results | Scales |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dental health status | Recording of dental caries on crowns and roots of teeth | Caries measurement using the WHO oral health survey measurement* guide in the redcap online research form | Measurement results: Good, bad, and medium | Ordinal |

| Demographic attributes | The investigated demographic attributes are the level of grade, age, and gender | Using the redcap online research form | • The level of grade corresponds to the grade currently assigned. • Age according to the age calculated from the year of birth • Gender is filled in with a choice of male or female fields |

Ordinal |

| Coding of Dental Health Status Primary and Permanent Teeth | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Teeth | Permanent Teeth | Condition/status | |

| Crown Code | Crown Code | Root | |

| A | 0 | 0 | Sound |

| B | 1 | 1 | Caries |

| C | 2 | 2 | Filled with caries |

| D | 3 | 3 | Filled, no caries |

| E | 4 | Missing due caries | |

| - | 5 | Missing for any other reason | |

| F | 6 | Fissure sealant | |

| G | 7 | 7 | Fixed dental prosthesis abutment, special crown, or veneer/implant |

| 8 | 8 | Unerupted teeth (crown)/unexposed root | |

| 9 | 9 | Not recorded | |

| Coding of def-t and DMF-T index | |||

| dmf-t index | DMF-T index | Indicators of caries severity | |

| dt | Number of decayed teeth in the primary dentition | ||

| mt | Number of teeth missing due to caries in the primary dentition | ||

| ft | Number of filled teeth in the primary dentition | ||

| deft | Number of decayed, missing due to caries and filled teeth in the primary dentition | ||

| DT | Number of decayed teeth in the permanent dentition | ||

| MT | Number of teeth missing due to caries in the permanent dentition | ||

| FT | Number of filled teeth in the permanent dentition | ||

| DMFT | Number of decayed, missing due to caries and filled teeth in the permanent dentition | ||

| Category of def-t and DMF-T index | |||

| dmf-t index | DMF-T index | Category | |

| <1.2 | Very low | ||

| 1.2–2.6 | Low | ||

| 2.7–4.4 | Moderate | ||

| 4.5–6.5 | High | ||

| >6.5 | Very high | ||

| <1.2 | Very low | ||

| 1.2–2.6 | Low | ||

| 2.7–4.4 | Moderate | ||

| 4.5–6.5 | High | ||

| >6.5 | Very high | ||

The researchers performed data analysis using frequency in descriptive analysis and calculated def-t and DMF-T index, classified high and low caries experience (Table 2) based on WHO-approved categories [17], and measured caries incidence using the prevalence formula [19]. We analysed the data using the Spearman rho correlation test to examine the correlation analytical test with a confidence interval of 95%. We performed recruitment, exposure, follow-up, and data collection of the study at Sekolah Indonesia Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, in June 2023.

3. RESULTS

The study results are shown in Tables 2-5. Table 2 demonstrates that despite being registered in grades 1, 5, and 6, the students’ ages are varying between 6-8 years and 10-12 years. The percentage ratio of the male and female respondents is nearly equivalent, differing by only 3.2%.

Table 3 shows the frequency and percentage distribution of the crown and the root of the maxillary children’s teeth. We categorised the distributions based on the children’s permanent teeth and their primary teeth.

Table 4 shows the frequency and percentage distribution of the crown and the root of the mandibular children’s teeth. Data categorized the distributions based on the children’s permanent teeth and their primary teeth. Tables 3 and 4 show that the dental crown status in all permanent teeth is 0 (healthy/sound), while the dental crown status in all primary teeth is A (caries). Root caries status was only detected in permanent teeth, particularly in teeth 26 and 36.

| Respondent Characteristics | F | % |

|---|---|---|

| Level Grade | ||

| 1 | 42 | 45.2 |

| 5 | 33 | 35.5 |

| 6 | 18 | 19.4 |

| Age | ||

| 6 | 19 | 20.4 |

| 7 | 20 | 21.5 |

| 8 | 2 | 2.2 |

| 10 | 15 | 16.1 |

| 11 | 30 | 32.3 |

| 12 | 7 | 7.5 |

| Gender | ||

| Boy | 45 | 48.4 |

| Girl | 48 | 51.6 |

| Dental Crown Status | F | % | Dental Root Status | F | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crown 18 | Root 18 | ||||

| Unerupted (code 8) | 93 | 100 | Not recorded (code 9) | 93 | 100.0 |

| Crown 17 | Root 17 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 9 | 10.8 | Not exposed (code 8) | 10 | 8.6 |

| Caries (code 1) | 1 | 1.0 | Not recorded (code 9) | 83 | 91.4 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 83 | 89.2 | |||

| Crown 16 | Root 16 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 65 | 69.9 | Not exposed (code 8) | 82 | 88.2 |

| Caries (code 1) | 17 | 18.3 | Not recorded (code 9) | 11 | 11.8 |

| Filled, no caries (code 3) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Unerupted (code 8) | 10 | 10.7 | |||

| Crown 15 or 55 | Root 15 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 30 | 32.2 | Not exposed (code 8) | 31 | 33.3 |

| Caries (code 1) | 1 | 1.1 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth) | 62 | 66.7 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 30 | 30.2 | |||

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 28 | 30.1 | |||

| Filled with caries primary teeth (code C) | 2 | 2.2 | |||

| Filled, no caries primary teeth (code D) | 2 | 2.2 | |||

| Crown 14 or 54 | Root 14 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 44 | 47.3 | Not exposed (code 8) | 45 | 48.3 |

| Filled with caries (code 2) | 1 | 1.1 | Not recorded (code 9) | 1 | 2.2 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 1 | 1.1 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth) | 47 | 50.5 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 25 | 26.8 | |||

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 19 | 20.4 | |||

| Filled with caries primary teeth (code C) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Filled, no caries primary teeth (code D) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Missing due to caries primary teeth (code E) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Crown 13 or 53 | Root 13 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 29 | 31.2 | Not exposed (code 8) | 29 | 31.2 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 7 | 7.5 | Not recorded (code 9) | 7 | 7.5 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 44 | 47.3 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth) | 57 | 61.3 |

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 12 | 12.9 | |||

| Filled, no caries primary teeth (code D) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Crown 12 or 52 | Root 12 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 52 | 55.9 | Not exposed (code 8) | 52 | 55.9 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 26 | 27.9 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth) | 41 | 44.1 |

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 14 | 15.1 | |||

| Filled, no caries primary teeth (code D) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Crown 11 or 51 | Root 11 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 67 | 72.0 | Not exposed (code 8) | 67 | 72.0 |

| Caries (code 1) | 1 | 1.1 | Not recorded (code 9) | 2 | 2.2 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 1 | 1.1 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth) | 24 | 25.8 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 10 | 10.7 | |||

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 12 | 12.9 | |||

| Filled, no caries primary teeth (code D) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Missing due to caries primary teeth (code E) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Crown 21 or 61 | Root 21 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 66 | 70.9 | Not exposed (code 8) | 67 | 72.0 |

| Filled with caries (code 2) | 1 | 1.1 | Not recorded (code 9) | 1 | 1.1 |

| Filled, no caries (code 3) | 1 | 1.1 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth) | 25 | 26.9 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 12 | 12.9 | |||

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 12 | 12.9 | |||

| Missing due to caries primary teeth (code E) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Crown 22 or 62 | Root 22 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 52 | 55.9 | Not exposed (code 8) | 53 | 56.9 |

| Caries (code 1) | 1 | 1.1 | Not recorded (code 9) | 1 | 1.1 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 1 | 1.1 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth) | 39 | 42.0 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 24 | 25.8 | |||

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 14 | 15.0 | |||

| Missing due to caries primary teeth (code E) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Crown 23 or 63 | Root 23 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 30 | 32.3 | Not exposed (code 8) | 30 | 32.3 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 6 | 6.4 | Not recorded (code 9) | 6 | 6.4 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 41 | 44.1 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth) | 57 | 61.3 |

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 14 | 15.0 | |||

| Missing due to caries primary teeth (code E) | 2 | 2.2 | |||

| Crown 24 or 64 | Root 24 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 41 | 44.1 | Not exposed (code 8) | 44 | 47.3 |

| Caries (code 1) | 3 | 3.2 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth) | 49 | 52.7 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 21 | 22.6 | |||

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 27 | 29.0 | |||

| Filled with caries primary teeth (code C) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Crown 25 or 65 | Root 25 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 26 | 27.9 | Not exposed (code 8) | 29 | 31.2 |

| Caries (code 1) | 3 | 3.2 | Not recorded (code 9) | 1 | 1.1 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 1 | 1.1 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth) | 63 | 67.7 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 29 | 31.2 | |||

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 31 | 33.2 | |||

| Filled with caries primary teeth (code C) | 2 | 2.2 | |||

| Filled, no caries primary teeth (code D) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Crown 26 | Root 26 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 68 | 73.1 | Sound (code 0) | 1 | 1.1 |

| Caries (code 1) | 16 | 17.2 | Caries (code 1) | 1 | 1.1 |

| Filled, no caries (code 3) | 1 | 1.1 | Not exposed (code 8) | 81 | 87.1 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 8 | 8.6 | Not recorded (code 9) | 10 | 10.7 |

| Crown 27 | Root 27 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 10 | 10.7 | Not exposed (code 8) | 12 | 12.9 |

| Caries (code 1) | 2 | 2.2 | Not recorded (code 9) | 81 | 87.1 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 81 | 87.1 | |||

| Crown 28 | Root 28 | ||||

| Unerupted (code 8) | 93 | 100 | Not recorded (code 9) | 93 | 100 |

Not recorded.

Table 4 displays that children of migrant workers fall into the low category of the DMF-T index, indicating that the presence of caries is only found in one permanent tooth per child. On the contrary, the def-t index classifies the children into a high category, showing caries present in three to four teeth per child.

Table 5 shows that the incidence of caries in adults' dental crowns is 53.76 percent, while the prevalence among children is 64.52 percent, which is considerably higher.

Table 6 shows that the prevalence of caries in adult tooth roots is only 1%; however, the calculation has not yet been determined to assess the prevalence of caries in children’s tooth roots.

| Dental Crown Status | F | % | Dental Root Status | F | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crown 18 | Root 18 | ||||

| Unerupted (code 8) | 93 | 100 | Not recorded (code 9) | 93 | 100.0 |

| Crown 17 | Root 17 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 9 | 10.8 | Not exposed (code 8) | 10 | 8.6 |

| Caries (code 1) | 1 | 1.0 | Not recorded (code 9) | 83 | 91.4 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 83 | 89.2 | |||

| Crown 16 | Root 16 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 65 | 69.9 | Not exposed (code 8) | 82 | 88.2 |

| Caries (code 1) | 17 | 18.3 | Not recorded (code 9) | 11 | 11.8 |

| Filled, no caries (code 3) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Unerupted (code 8) | 10 | 10.7 | |||

| Crown 15 or 55 | Root 15 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 30 | 32.2 | Not exposed (code 8) | 31 | 33.3 |

| Caries (code 1) | 1 | 1.1 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth) | 62 | 66.7 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 30 | 30.2 | |||

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 28 | 30.1 | |||

| Filled with caries primary teeth (code C) | 2 | 2.2 | |||

| Filled, no caries primary teeth (code D) | 2 | 2.2 | |||

| Crown 14 or 54 | Root 14 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 44 | 47.3 | Not exposed (code 8) | 45 | 48.3 |

| filled with caries (code 2) | 1 | 1.1 | Not recorded (code 9) | 1 | 2.2 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 1 | 1.1 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth) | 47 | 50.5 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 25 | 26.8 | |||

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 19 | 20.4 | |||

| Filled with caries primary teeth (code C) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Filled, no caries primary teeth (code D) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Missing due to caries primary teeth (code E) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Crown 13 or 53 | Root 13 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 29 | 31.2 | Not exposed (code 8) | 29 | 31.2 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 7 | 7.5 | Not recorded (code 9) | 7 | 7.5 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 44 | 47.3 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth) | 57 | 61.3 |

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 12 | 12.9 | |||

| Filled, no caries primary teeth (code D) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Crown 12 or 52 | Root 12 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 52 | 55.9 | Not exposed (code 8) | 52 | 55.9 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 26 | 27.9 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth) | 41 | 44.1 |

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 14 | 15.1 | |||

| Filled, no caries primary teeth (code D) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Crown 11 or 51 | Root 11 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 67 | 72.0 | Not exposed (code 8) | 67 | 72.0 |

| Caries (code 1) | 1 | 1.1 | Not recorded (code 9) | 2 | 2.2 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 1 | 1.1 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth) | 24 | 25.8 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 10 | 10.7 | |||

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 12 | 12.9 | |||

| Filled, no caries primary teeth (code D) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Missing due to caries primary teeth (code E) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Crown 21 or 61 | Root 21 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 66 | 70.9 | Not exposed (code 8) | 67 | 72.0 |

| Filled with caries (code 2) | 1 | 1.1 | Not recorded (code 9) | 1 | 1.1 |

| Filled, no caries (code 3) | 1 | 1.1 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth) | 25 | 26.9 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 12 | 12.9 | |||

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 12 | 12.9 | |||

| Missing due to caries primary teeth (code E) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Crown 22 or 62 | Root 22 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 52 | 55.9 | Not exposed (code 8) | 53 | 56.9 |

| Caries (code 1) | 1 | 1.1 | Not recorded (code 9) | 1 | 1.1 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 1 | 1.1 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth) | 39 | 42.0 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 24 | 25.8 | |||

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 14 | 15.0 | |||

| Missing due to caries primary teeth (code E) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Crown 23 or 63 | Root 23 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 30 | 32.3 | Not exposed (code 8) | 30 | 32.3 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 6 | 6.4 | Not recorded (code 9) | 6 | 6.4 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 41 | 44.1 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth) | 57 | 61.3 |

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 14 | 15.0 | |||

| Missing due to caries primary teeth (code E) | 2 | 2.2 | |||

| Crown 24 or 64 | Root 24 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 41 | 44.1 | Not exposed (code 8) | 44 | 47.3 |

| Caries (code 1) | 3 | 3.2 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth) | 49 | 52.7 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 21 | 22.6 | |||

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 27 | 29.0 | |||

| Filled with caries primary teeth (code C) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Crown 25 or 65 | Root 25 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 26 | 27.9 | Not exposed (code 8) | 29 | 31.2 |

| Caries (code 1) | 3 | 3.2 | Not recorded (code 9) | 1 | 1.1 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 1 | 1.1 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth) | 63 | 67.7 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 29 | 31.2 | |||

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 31 | 33.2 | |||

| Filled with caries primary teeth (code C) | 2 | 2.2 | |||

| Filled, no caries primary teeth (code D) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Crown 26 | Root 26 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 68 | 73.1 | Sound (code 0) | 1 | 1.1 |

| Caries (code 1) | 16 | 17.2 | Caries (code 1) | 1 | 1.1 |

| Filled, no caries (code 3) | 1 | 1.1 | Not exposed (code 8) | 81 | 87.1 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 8 | 8.6 | Not recorded (code 9) | 10 | 10.7 |

| Crown 27 | Root 27 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 10 | 10.7 | Not exposed (code 8) | 12 | 12.9 |

| Caries (code 1) | 2 | 2.2 | Not recorded (code 9) | 81 | 87.1 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 81 | 87.1 | |||

| Crown 28 | Root 28 | ||||

| Unerupted (code 8) | 93 | 100 | Not recorded (code 9) | 93 | 100 |

| Crown 38 | Root 38 | ||||

| Unerupted (code 8) | 93 | 100 | Unerupted (code 8) | 93 | 100 |

| Crown 37 | Root 37 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 14 | 15.1 | Not exposed (code 8) | 17 | 18.3 |

| Caries (code 1) | 3 | 3.2 | Not recorded (code 9) | 76 | 81.7 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 76 | 81.7 | |||

| Crown 36 | Root 36 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 56 | 60.2 | Caries (code 1) | 1 | 1.1 |

| Caries (code 1) | 29 | 31.2 | Not exposed (code 8) | 85 | 91.4 |

| Filled with caries (code 2) | 1 | 1.1 | Not recorded (code 9) | 7 | 7.5 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 7 | 7.5 | |||

| Crown 35 | Root 35 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 31 | 33.3 | Not exposed (code 8) | 32 | 34.4 |

| Caries (code 1) | 1 | 1.1 | Not recorded (code 9) | 1 | 1.1 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 1 | 1.1 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth) | 60 | 64.5 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 25 | 26.9 | |||

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 33 | 35.5 | |||

| Filled with caries primary teeth (code C) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Missing due to caries primary teeth (code E) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Crown 34 or 74 | Root 34 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 44 | 47.3 | Not exposed (code 8) | 44 | 47.3 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 22 | 23.6 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth | 49 | 52.7 |

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 25 | 26.9 | |||

| Filled with caries primary teeth (code C) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Filled, no caries primary teeth (code D) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Crown 33 or 73 | Root 33 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 41 | 44.1 | Not exposed (code 8) | 41 | 44.1 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 2 | 2.2 | Not recorded (code 9) | 2 | 2.2 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 44 | 47.3 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth) | 50 | 53.7 |

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 5 | 5.3 | |||

| Missing due to caries primary teeth (code E) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Crown 32 or 72 | Root 32 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 60 | 64.5 | Not exposed (code 8) | 60 | 64.5 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 27 | 29.0 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth | 33 | 35.5 |

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 2 | 2.2 | |||

| Filled with caries primary teeth (code C) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Missing due to caries primary teeth (code E) | 3 | 3.2 | |||

| Crown 31 or 71 | Root 31 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 80 | 86.0 | Not exposed (code 8) | 80 | 86.0 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 11 | 11.8 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth | 13 | 14.0 |

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 2 | 2.2 | |||

| Crown 41 or 81 | Root 41 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 78 | 83.8 | Not exposed (code 8) | 78 | 83.9 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 13 | 14.0 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth | 15 | 16.1 |

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 2 | 2.2 | |||

| Crown 42 or 82 | Root 42 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 61 | 65.6 | Not exposed (code 8) | 61 | 65.6 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 28 | 30.1 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth | 32 | 34.4 |

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Missing due to caries primary teeth (code E) | 3 | 3.2 | |||

| Crown 43 or 83 | Root 43 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 45 | 48.4 | Not exposed (code 8) | 45 | 48.4 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 2 | 3.2 | Not recorded (code 9) | 2 | 2.2 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 42 | 45.1 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth) | 46 | 49.4 |

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 4 | 4.3 | |||

| Crown 44 or 84 | Root 44 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 39 | 41.9 | Not exposed (code 8) | 40 | 43.0 |

| Caries (code 1) | 1 | 1.1 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth | 53 | 57.0 |

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 26 | 27.9 | |||

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 23 | 24.7 | |||

| Filled with caries primary teeth (code C) | 1 | 1..1 | |||

| Filled, no caries primary teeth (code D) | 2 | 2.2 | |||

| Missing due to caries primary teeth (code E) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Crown 45 or 85 | Root 45 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 35 | 37.6 | Not exposed (code 8) | 36 | 38.7 |

| Caries (code 1) | 1 | 1.1 | Not recorded (code 9) | 2 | 2.2 |

| Missing due to caries (code 4) | 1 | 1.1 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth) | 55 | 59.1 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Sound primary teeth (code A) | 20 | 21.5 | |||

| Caries primary teeth (code B) | 31 | 33.3 | |||

| Filled with caries primary teeth (code C) | 3 | 3.2 | |||

| Filled, no caries primary teeth (code D) | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Crown 46 | Root 46 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 60 | 64.5 | Not exposed (code 8) | 87 | 93.5 |

| Caries (code 1) | 27 | 29.0 | Not applicable (no code for primary teeth | 6 | 6.5 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 6 | 6.5 | |||

| Crown 47 | Root 47 | ||||

| Sound (code 0) | 20 | 21.5 | Not exposed (code 8) | 22 | 23.7 |

| Caries (code 1) | 2 | 2.2 | Not recorded (code 9) | 71 | 75.3 |

| Unerupted (code 8) | 71 | 76.3 | |||

| Crown 48 | Root 48 | ||||

| Unerupted (code 8) | 93 | 100 | Unerupted (code 8) | 93 | 100 |

| Index | Sum | Value Index | Explanation | Index | Sum | Value Index | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMFT | 113 | 1,22 | Low | def | 435 | 3,77 | High |

| n | 93 | n | 93 |

| Prevalence | Sum | % | Prevalence | Sum | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permanent dentition crown caries | 50 | 53,76 | Children's dental crown caries | 60 | 64,52 |

| N | 93 | 93 |

Table 7 reveals numerous negative correlations were found between dental health status and the level of grade and age, while no correlation exists between the oral health status and the gender of the migrant children. The majority of negative correlations are found between dental health status and the level of grade, age, and gender.

4. DISCUSSION

Table 1 shows that even though the class levels are 1,5 and 6, the ages at these levels vary greatly, namely 6-8 years and 10-12 years. The age at this class level is different from the observations of researchers, who found that the average school child in Indonesia was 6-7 years old in grade 1, and the average age was 11-12 years in grade 3. This result can be compared with previous research, as no previous research has reported this finding. This may happen because migrant children have limited access to education due to barriers either from educational institutions, host country policy, family, or society in general [20]. The percentage ratio of male and female respondents in this study is nearly equivalent, differing by only 3.2%. This percentage is likely to represent the gender balance in the population representation and statistical power [21].

Table 2 shows the status of the adult crown with code 0 in all permanent teeth, indicating sound teeth, and all primary teeth with code A, indicating caries. Root status caries only occur in permanent teeth, specifically teeth 26 and 36. These results are in accordance with Praveen's research, which still found healthy teeth in 6% of permanent teeth and in the deciduous teeth group [22].

Table 3 demonstrates the DMF-T index of migrant children in the low category, in which dental caries only occur at one or two teeth per child. Meanwhile, migrant children’s def-t index is high, indicating caries affects three to four teeth per child. These results are in line with a study conducted by Zhang et al. [23], which stated that the DMFT index and higher caries incidence were found among migrant children, and a study by Ferrazzano et al. revealed that caries among migrant children were more prevalent in primary teeth, although the index was not higher than that of permanent teeth [24].

Table 4 displays that migrant workers’ children fall into the low category of the DMF-T index. On the contrary, the def-t index classifies the children into a high category. This result is in line with a study by Liu that revealed the children of the migrant workers had insufficient income [25] due to their bad habits, lack of access, and gender issues [25], as well as the effect of parental migration [26].

Table 5 shows that the prevalence of caries in crowns of permanent dentition migrant workers is 53.76%, and the prevalence of caries in children's dental crowns is 64.52%. The prevalence of caries in adults’ dental crowns is lower than that of migrant children. This result is in agreement with a study by Lamont, which showed that the prevalence of root caries was different from that of crown caries in the younger and older group [27]. These findings, however, can be compared with the results of a study that revealed the caries prevalence among children in Asia was 52,6% and among adults’ permanent teeth was 58.8% [28].

The prevalent scores of adults’ and children’s dental crowns are higher than the caries scores in Asians [28]. The results mentioned above highlight the importance of policymakers and health care providers paying particular attention in order to enable the provision of oral health education programmes and interventions for adults and children, as well as dental health services, particularly for mothers, nurses, and child educators. It is also necessary to plan for the distribution of low-cost oral health education programs and services, as well as simple access to these services for children through the national healthcare system [28].

Table 6 indicates that the prevalence of dental root caries among the adult population was 1%, and the caries root prevalence among the children of migrant workers was indeterminable. This finding differs from a systematic review by Pentapati, which showed its prevalence at 3.69% - 96.47% or over [29]. This outcome may result from various reports and measurements related to the calculation of caries prevalence [29, 30]. Several factors, such as education degree, household income, and residential area, may contribute to the diverse distribution of dental root caries. These results may lead to inequalities in dental knowledge and use of dental health services, leading to inequalities in the distribution of root caries [30].

Table 7 illustrates the predominant negative correla-tion between dental health status and grade level. This is in line with a study by Mishu et al. [31], which stated that the number of decayed teeth is significantly reversed with age, and Kumar et al. [32] also mentioned that statistically significant differences were found when comparing age groups. This may happen as a result of, according to some research, age-induced caries [32]. Age is a demographic factor that affects caries development, as found in the theory of social determinants [33], and the susceptibility of teeth to caries can occur because permanent teeth show a decrease in permeability with increasing age [34]. Oral health status increases with age. This can occur due to physiological changes in age, nutrition, medical conditions, and medications [35].

Table 7 shows there was no correlation between dental health status and age. This is in contrast with a study conducted by Geethapriya et al. [36], which revealed that age was not associated with children’s oral health status. Nonetheless, as children get older, it is expected that their level of knowledge about oral health will also increase, either from their experiences at home, school, or in the social environment. This statement is in line with a study by Lamont [27] that stated its prevalence correlates with increasing age. Furthermore, as an individual grows older, the dental and oral health changes as well [36] Age-induced caries may result in several changes within various timelines; however, it may also have a direct impact on how the disease develops [37]. Poor oral hygiene and bad eating habits are the primary causes of dental caries, and the condition may worsen with age [37].

Tables 7-9 shows that there is no correlation between dental health status and the gender of the children of migrant workers. This finding is in accordance with a study by Ferrazzano et al., which concluded that gender was not associated with dental caries [24]; however, this is in contrast with Kumar et al.’s research, which mentioned that gender could greatly affect the pain scores caused by caries [32]. In addition, Shaffer et al.s’ Study also discovered that dental caries among females was consistently higher compared to males [38]. These disparate results can be resolved by establishing school-based community dental health services that can contribute to reducing the gap in dental health status between migrant and non-migrant children [23].

| Prevalence | Sum | % | Prevalence | Sum | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Root caries in permanent teeth | 1 | 1 | Root caries in children | Not applicable | - |

| n | 93 |

| Teeth Number Condition | Grade | Age | Gender | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation Coeficient | P Value | Correlation Coeficient | P Value | Correlation Coeficient | P- Value | |

| Crown 18 | -0,12 | 0,252 | -0,105 | 0,319 | -0,012 | 0,906 |

| Crown 17 | -0,342 | 0,001* | -0,369 | 0,000* | -0,117 | 0,262 |

| Crown 16 | -0,050 | 0,635 | -0,095 | 0,363 | 0,137 | 0,189 |

| Crown_15_55 | -0,481 | 0,000* | -0,492 | 0,000* | -0,056 | 0,594 |

| Crown_14_54 | -0,696 | 0,000* | -0,735 | 0,000* | -0,003 | 0,980 |

| Crown_13_53 | -0,648 | 0,000* | -0,656 | 0,000* | -0,116 | 0,269 |

| Crown_12_52 | -0,842 | 0,000* | -0,812 | 0,000* | 0,066 | 0,529 |

| Crown_11_51 | -0,569 | 0,000* | -0,609 | 0,000* | -0,002 | 0,984 |

| Crown_21_61 | -0,620 | 0,000* | -0,659 | 0,000* | 0,068 | 0,516 |

| Crown_22_62 | -0,826 | 0,000* | -0,822 | 0,000* | 0,009 | 0,935 |

| Crown_23_63 | -0,547 | 0,000* | -0,577 | 0,000* | -0,075 | 0,476 |

| Crown_24_64 | -0,735 | 0,000* | -0,736 | 0,000* | -0,019 | 0,854 |

| Crown_25_65 | -0,481 | 0,000* | -0,415 | 0,000* | -0,081 | 0,441 |

| Crown_26 | -0,159 | 0,128 | -0,246 | 0,017 | 0,126 | 0,227 |

| Crown_27 | -0,403 | 0,000* | -0,396 | 0,000* | -0,141 | 0,177 |

| Crown_28 | -0,203 | 0,051 | -0,152 | 0,146 | -0,055 | 0,602 |

| Crown_38 | -0,148 | 0,158 | -0,108 | 0,303 | -0,070 | 0,503 |

| Crown_37 | -0,407 | 0,000* | -0,41 | 0,000* | -0,136 | 0,192 |

| Crown_36 | -0,014 | 0,892 | -0,027 | 0,795 | 0,053 | 0,615 |

| Crown_35_75 | -0,549 | 0,000* | -0,549 | 0,000* | -0,090 | 0,389 |

| Crown_34_74 | -0,697 | 0,000* | -0,743 | 0,000* | -0,089 | 0,395 |

| Crown_33_73 | -0,711 | 0,000* | -0,704 | 0,000* | -0,075 | 0,476 |

| Crown_32_72 | -0,750 | 0,000* | -0,784 | 0,000* | 0,086 | 0,411 |

| Crown_31_71 | -0,413 | 0,000* | -0,445 | 0,000* | -0,052 | 0,621 |

| Crown_41_81 | -0,449 | 0,000* | -0,502 | 0,000* | 0,005 | 0,962 |

| Crown_42_82 | -0,736 | 0,000* | -0,768 | 0,000* | 0,067 | 0,526 |

| Crown_43_83 | -0,723 | 0,000* | -0,769 | 0,000* | -0,023 | 0,828 |

| Crown_44_84 | -0,640 | 0,000* | -0,702 | 0,000* | -0,029 | 0,784 |

| Crown_45_85 | -0,622 | 0,000* | -0,705 | 0,000* | -0,090 | 0,391 |

| Crown_46 | 0,171 | 0,102 | 0,149 | 0,154 | 0,210 | 0,043 |

| Crown_47 | -0,469 | 0,000* | -0,511 | 0,000* | -0,066 | 0,530 |

| Crown_48 | -0,235 | 0,023 | -0,174 | 0,000* | -0,054 | 0,606 |

The different findings mentioned above may exist due to several key factors, including age, gender, maternal education, socioeconomic status, regular oral hygiene maintenance, oral health parents’ awareness, and sugar consumption. Moreover, due to the high incidence of dental caries, it is crucial to address socioeconomic and behavioral determinants that are changeable by the implementation of effective policies and programs for oral health management [38].

In order to prevent dental caries among children, it is important that parents promote oral hygiene and acknowledge the significance of oral health education programs [39]. Moreover, a particular emphasis on strengthening research in regional oral health will help enhance knowledge and comprehension regarding vital public health problems within the area [40].

Furthermore, oral healthcare providers can detect oral health issues early, make referrals to the oral health system, and facilitate effective communication with migrants in order to promote knowledge and access regarding oral health [11]. It appears that these improvements must also include socially marginalized child populations, such as migrants, where the prevalence of dental caries remains high. Migrant status continues to be regarded as a social vulnerability linked to oral health [23]. The limitation of the study is that it only examined three demographic attributes out of the many demographic attributes that are predicted to influence dental health status

CONCLUSION

The DMFT index of migrant workers’ children is low, while the deft index is high. It means the children of migrant workers have caries experience in 1-2 permanent teeth. Meanwhile, the deft index is high, which means the children of migrant workers have caries experience at 3-4 primary teeth. The prevalence of crown and root caries among migrant children is not particularly high, with 60 children (64.5% of the 93 children) having caries experience. The study finds negative correlations between dental health status and the educational level and age of the migrant children. This means that oral health has become increasingly poor at higher levels of education and age. However, the gender of the study population is not associated with the dental health status. The research’s implications include the development of policies to enhance dental and oral health promotion in elementary schools, particularly at higher educational and age levels.

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTION

It is hereby acknowledged that all authors have accepted responsibility for the manuscript's content and consented to its submission. They have meticulously reviewed all results and unanimously approved the final version of the manuscript.

ABBREVIATION

| ICDAS | = International Caries Detection and Assessment System |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The research has followed ethical provisions from the Padjadjaran University Health Research Ethics Committee with register number 2304070641.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Prior to the study, the respondents’ guardians or parents had accepted and approved the informed consent.